Review, 22nd Biennale of Sydney: NIRIN, MCA, AGSA, Cockatoo Island

The Biennale of Sydney is an opportunity to think about what matters most in an era of technology and capitalism

Culture, like many words, has evolved to have several distinct senses. Etymologically, it comes from the Latin verb colere, which primarily means to cultivate land. By extension, cultivation comes to be virtually synonymous with inhabitation, so that incola means inhabitant and a colonia is a place that is farmed or inhabited.

Figuratively, the word refers to the cultivation of the mind through education. A cultivated person is one whose mind has been refined through study, particularly of subjects that develop the ability to think, judge and discriminate, and through the enjoyment of arts, which develop imagination and sensibility; training in practical skills and techniques is not the same as cultivation.

From this sense comes the idea of culture as the ensemble of intellectual and artistic pursuits, including theatre, music, art and literature, from which governments subtract education and to which they add commercial entertainment to make up what they call the cultural sector.

A different sense of culture arose in the romantic period, particularly as articulated by Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803), whose ideas had an immense influence, particularly on contemporary and later philosophers and linguists. Rejecting the universal claims of Enlightenment rationalism as the cloak of a French hegemony, Herder argued for the value of the particular traditions and even ways of thinking — embodied as he showed in language — of different peoples.

The habits, the way of life and the world view of peoples who have lived together for centuries or millennia in a particular place were thus recognised as having a kind of organic unity — another romantic theme, as we saw recently — which was given the name of culture. And this new concept became the foundation of modern anthropology: the study of the lives, customs, beliefs, myths and rituals of different peoples.

But this emerging awareness of difference had arisen as a reaction to the Enlightenment’s promotion of universal standards and values, including political liberalism and the principle of the universal rights of man. It also could form the basis of political nationalism and, when combined with new theories of evolution and genetics, produce a fundamentally new kind of racial theory and exacerbate conflict between ethnic groups.

From an anthropological point of view, however, the most striking thing is that this new awareness of culture corresponded to an acceleration in the decline of cultural diversity around the world, which has now long become irreversible.

Cultures have always been in a state of evolution, except where isolated from outside contact. Otherwise, there is a constant process of learning from other peoples, through imitation and adaptation, or through population drift, migration, settlement and conquest. Generally there is a spontaneous attraction to superior technology or systems, as in the case of Khmer civilisation in Cambodia, which arose from an imitation of the Indian model.

One of the most interesting patterns in cultural transmission is when a less advanced group adopts the culture of a more advanced people after conquering them: we can see this with the Turks in Iran and later with the Mongols in Iran and China. These peoples invaded far more sophisticated cultures and were civilised by those they had defeated.

By the end of the 18th century, however, the progress of the Industrial Revolution had fundamentally changed the balance of power between Europe and the rest of the world, including the civilisations of South and East Asia. European colonial expansion, supported by superior technology and armaments, became impossible to resist, and in the longer term became the vehicle for the massive technology transfer that has modernised the whole world and created, especially in East Asia, economic and industrial rivals to the West.

And this brings us to where we are today, in what can seem like a bland and post-cultural world, especially in new-world nations such as Australia and America, where cultures come from all over the world to die in the wasteland of consumer malls. At the same time the tourist business, now suspended for the time being, lives on the quest for dwindling vestiges of local colour and traditional authenticity.

What are we to think about this? The superficiality and materialism of a consumer economy can be suffocating; the recent COVID pause has given many of us the opportunity to realise how little of that world we miss when we are forced into isolation. The advertisements that crowd around us in city streets, in print media and online seem more than ever like importunate beggars soliciting our money, and the goods and services they offer feel less compelling than ever.

We instinctively prefer the colour, variety and vitality of living cultures, and it is tempting to see traditional and even tribal cultures as an alternative to the post-cultural world of modern capitalism. But the truth is much more complicated and less palatable. In the first place all traditional cultures are conservative, and tribal cultures are extremely conservative: this is how they have persisted and served as the moral infrastructures of their communities. They are highly prescriptive about hierarchies of age and status and about gender roles. They allow no room for dissent and their closed systems of belief, foreign to critical thinking, make it almost impossible for dissent to arise.

They are also dominated by belief systems that most people today would regard as superstitious and that serve to support social structures that can be oppressive and even violent. None of this would be acceptable to any modern person; no matter what our political persuasion, we are all in fact heirs to the Enlightenment in our belief in human rights and principles of universal justice that must override the vagaries of social customs.

But even if we could condone any of these models, the truth is that they are all to a greater or lesser extent broken. There is not a culture in the world today, with the possible exception of some remote pockets of Amazonians, that is functioning with its traditional social, economic and belief systems. All are in various stages of accommodation to the modern economic and technological world, from China, Japan and South Korea, which have become leaders of that world, to tribal peoples who are still struggling to adapt.

The challenge for everyone, including the Western world that was originally responsible for setting the human race on this new trajectory, is how to negotiate a new understanding of culture in the globalised order of things. We should be able to do better than to end up with a world of identical shopping malls differentiated only by token scraps of culture like folk costumes on festive days.

Japan is an interesting model, adopting modern science and technology while also preserving a very strong sense of traditional beliefs, customs and social ceremony. The Chinese development has been even more spectacular, if less harmonious, and in general the success of East Asian migrants in countries such as the US and Australia bears witness to a remarkable ability to adapt and to outstrip most other ethnic and cultural groups in these countries.

These are the issues implicitly raised, but not properly faced, in this year’s Biennale of Sydney, which has just been reopened after the COVID hibernation. The focus is on traditional, tribal and indigenous cultures that survive around the world, but the general tone is one of lamentation or blame, most notably in the dismal series of displays at the Art Gallery of NSW.

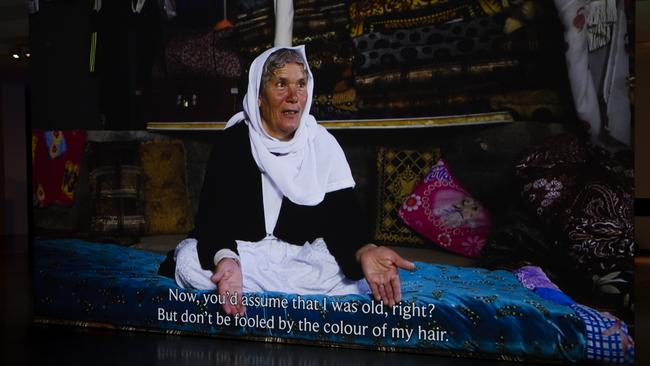

At the Museum of Contemporary Art, the most interesting pieces, documentary in nature rather than aesthetic, are devoted to the Ainu culture of northern Japan and a rather melancholy documentation of the nostalgic phenomenon of temporary tattoos, a pale shadow of the traditional practice, and to the Yazidi people, who were hounded from their homes and subjected to appalling abuse by Islamic State.

Cockatoo Island is more sparsely filled than usual, and few of the displays are memorable. Several are strident complaints, which are of limited effectiveness even when they have something legitimate to complain about. Again and again we encounter the disjunction between words and work that is a regular feature of such exhibitions. In fact the labels, where the challenge is to squeeze as many inane buzzwords as possible into a single sentence, are often more entertaining than the exhibits they are supposed to describe.

One piece “emerge(s) from a desire to articulate a position in regards to global warming which is not rooted only in a desire for human survival, but beyond that in a deep comprehension of the Earth as entanglement”. Another artist declares “my work revolves around notions of power and the mechanisms at play in contemporary society”. Yet another “envisions a body that transcends colonial binaries and expedient figurations of gender, sexuality and humanness which keep us separated from the natural world”.

The most striking work on the island was a set of objects belonging to the Voodoo cults of Haiti, like a sort of Mad Max bricolage of the wreckage of several cultures: aesthetically effective in a certain way, yet animated by violent, phallic sexuality, dark superstition and the menace of brutal death; not really a culture one wants to have anything to do with.

But ultimately, and less obviously, part of the problem lies in the nature of these cultures themselves. As I mentioned a couple of months ago when the Biennale opened, the self-referentiality of all very traditional cultures can make it hard for them to see beyond their own horizons, to change and to evolve.

Old commonplaces and familiar narratives about race and colonialism have become less relevant today. The scientific, technological and economic order of the modern world was originally European; it developed into an American order, and is now as much East Asian as anything else. The important thing is not race but economic systems, which are quite different.

A couple of years ago the leader of the NSW Labor opposition lost an election after telling a group of voters at what he thought was a private meeting that their homes would all be bought by Asians with PhDs. This was a crude appeal to racial resentment and fear; but he could have gone further and told them that these PhDs were raising the bar for success in the modern world. The mediocrity and complacency of middle Australia would have to change, starting with attitudes to education.

There are plenty of things about the new international order we legitimately criticise and that we should try to change: above all, the mindless consumerism and the consequent destruction of the environment. But we must all learn to accommodate these conditions or risk becoming a permanent underclass. The most urgent adaptation is economic, but the more important one is cultural, finding a way, like the Japanese, of preserving the values we hold dear while surviving in radically changed conditions.

The 22nd Biennale of Sydney: NIRIN is at Art Gallery of NSW and Artspace until September 27; Campbelltown Arts Centre until October 11; Museum of Contemporary Art and Cockatoo Island until September 6.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout