King Charles: Humphries ‘made us laugh at ourselves’

‘This cultured and erudite man could not have been more different from his various stage incarnations,’ the message from the King read.

Of the dozens of film clips of Barry Humphries circulating on YouTube, one segment stands out as an example of his comic genius and audacity.

It’s from the Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium in 2013. Charles and Camilla, then the Prince of Wales and Duchess of Cornwall, are sitting in the royal box. Humphries as Dame Edna comes into the box, resplendent in spangles and mauve do, and takes the seat next to Camilla – reaching across to give the duchess a reassuring touch on the arm.

What happens next is priceless. An usher comes in and hands Edna a ticket. First a grimace, then a look of relief. “I’m so sorry,” Edna says, giving Camilla’s hand a squeeze. “They’ve found me a better seat.”

The whole performance lasts barely 40 seconds, and Humphries has the audience in stitches. The future king and queen can hardly contain their laughter. Lese-majesty never looked so much fun.

Humphries and the King clearly had a rapport that included a shared sense of humour. Charles had called Humphries when he was ill in St Vincent’s Hospital earlier this year, and led the tributes when Humphries died on April 22, at age 89.

The King has written a message for the state memorial for Humphries on Friday at the Sydney Opera House. The Australian Chamber Orchestra – the finest of Australia’s classical ensembles, and a favourite of Humphries – performed at the event.

The long-awaited memorial, almost eight months after Humphries’ death and private funeral, follows a brouhaha over whether NSW or Victoria would host the occasion, and over the choice of entertainment reporter Richard Wilkins as host.

After reports that some family and friends were boycotting the memorial because of disagreements about it, Humphries’ widow, Lizzie Spender, and three of his children will be attending, a source tells this writer. Daughter Emily has said she is unable to attend.

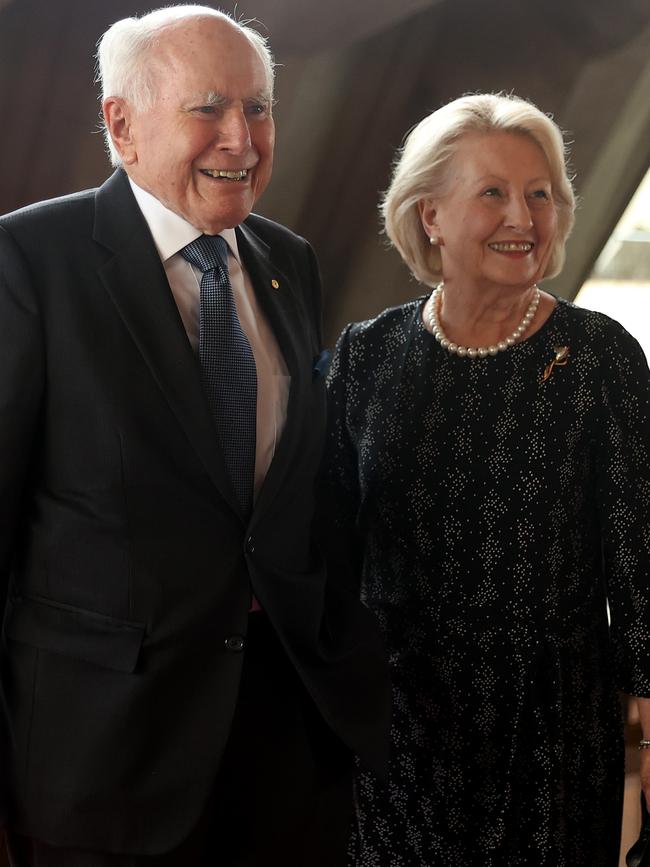

Hundreds of people gathered at The Opera House on Friday for the funeral, including politicians such as former Liberal Prime Ministers Malcolm Turnbull and John Howard, former Speaker of the House Bronwyn Bishop, actors Jackie Weaver and Barry Crocker, barrister Geoffrey Robertson, and musician Leo Sayer.

Humphries’ two sons, Rupert and Oscar, arrived with his spouse Elizabeth Spender.

The service commenced at 11 a.m. in the concert hall, featuring a musical tribute by the Australian Chamber Orchestra performing Johann Sebastian Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor.

After a performance of Australia’s national anthem by baritone Peter Coleman-Wright, government minister Tony Burke recited a message from His Majesty King Charles III.

“Barry Humphries, through his creations, poked and prodded us, exposed to tensions, punctured pomposity, surfaced insecurities, but most of all made us laugh at ourselves,” he said.

“This cultured and erudite man, with his love of literature and the visual arts, and passion for Weimar cabaret, could not have been more different from his various stage incarnations.

“May our gladioli bloom in celebration of his memory.”

Speaking in a video message, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese remembered Humphries as a comedic giant who “brought such joy to every part of Australia.

“Just as Parliament ultimately answers to the Governor General, Dame Edna and Sir Les also answered to a higher power. Barry Humphries,” Albanese said.

“No matter how unruly his creations became, it was Barry who had the final word, and what a word it was.

“Barry had the ultimate power, a power he exercised with a glee that never knew any bounds.

“Just like this place he brought people from every state and territory together. And in the process, this genius this comedic giant brought such joy to every part of Australia.”

The ABC has compiled a special commemorative program about Humphries, Barry Humphries in His Own Words, to screen on Friday evening.

Director Bruce Beresford, who first met Humphries in 1963 at his flat in Little Venice, London, remembered him as “A great talent. A great friend. A great Australian.”

Beresford shared a story from a time when Humphries was battling alcohol addiction in the 1960s. “At one theatre he knew he was first on stage after interval. He ran from a nearby pub and managed to reach the theatre just as the interval ended. He dashed into the wings and then onto the stage,” he recalled. “The only problem was he was in the wrong theatre, in the wrong play.”

He said Humphries never touched a drop of alcohol after 1972.

Humphries’ daughter Tessa, recited one of her father’s poems from the 1970s: Wattle Park Blues. “I’m hoping it will bring a bit of a genteel Melbourne charm to his salubrious Sydney,” she said.

Humphries’s sons, Oscar and Rupert, shared anecdotes from their early life with their father. “My childhood was spent either wishing I was with my dad or following him around on tour,” Rupert said. “I’d hang out in theaters, concert halls and TV studios, getting to spend time with him in that precious window between his afternoon nap and the show starting.

“My favourite smell growing up was the acetone in his little pink pots of nail polish remover.

“He taught me a love of traveling, books, and learning; the power of being outrageous; how to be completely yourself; and the importance of creativity above all else.”

Oscar said that his father had lived “a life in two acts.”

“The chaos of addiction, and then from the 70s onwards, his sobriety,“ he said. “He was enormously proud of it, and he regarded it as his greatest achievement.”

Further video tributes from famous friends, such as actor Rob Brydon, musician Sir Elton John, restaurateur Rick Stein, Rupert Murdoch, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, and British theatrical producer Cameron Mackintosh were beamed onto the Opera House screens.

Reflecting on Humphries’ comic genius, Sir Elton John shared, “Barry Humphries was one of the funniest people in the world, but you know that.” In a heartening wish for the gathering, he added, “I hope you all have the most wonderful day there and celebrate with laughter, because that was what Barry was all about.”

At the close of the ceremony, MC Richard Wilkins announced that the sails of the Sydney Opera House will be lit with a tribute to Humphries from 8.30pm.

It is a glorious televisual scrapbook of Humphries’ characters and interview footage with the great comedian, in which he explains their origins and evolution – none so extraordinary as the road to gigastardom of Mrs Norm Everage of Moonee Ponds. More than anything, the program demonstrates Humphries’ almost preternatural gift for finding comedy in almost any setting.

The clip with Charles and Camilla in the royal box is included, of course, as are examples of Humphries’ classic one-liners. Who else but Dame Edna could say to a rather renovated Tom Jones: “I’m trying to be ageless. I’ve had a little work done, but not quite as much as some of us.”

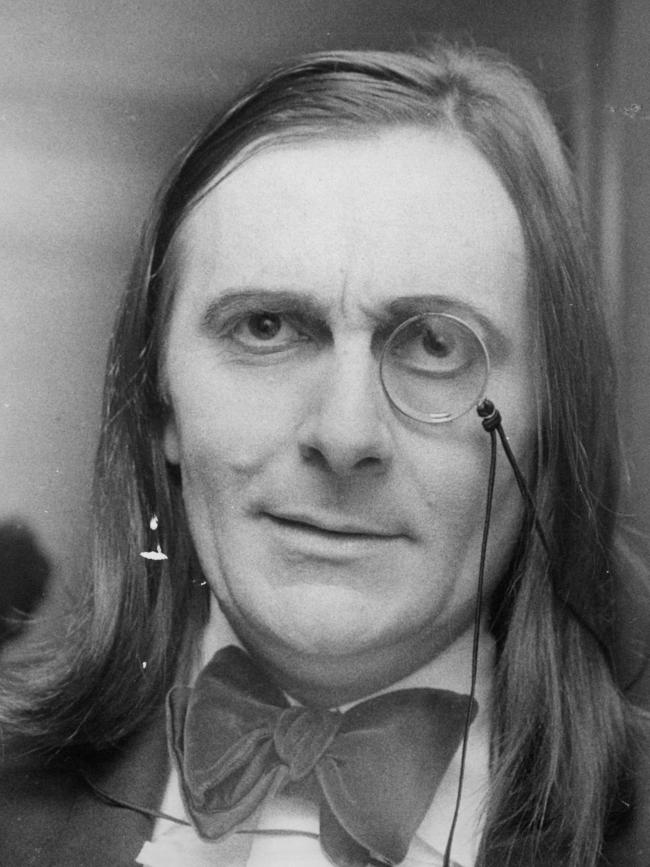

The program opens with one of Humphries’ lesser-known characters – pipe-smoking, chin-stroking academic Neil Singleton. With his mutton-chops and pipe, Singleton introduces Humphries as he is about to appear on the small screen. “I along with a lot of other Australians have been watching the stage career of Mr Barry Humphries with a good deal of amusement and of course the inevitable reservations,” he says. “And so I, along with a lot of others, are going to be par-ticu-lar-ly interested tonight to see how the much-vaunted Humphries shapes in the more exacting and complex media of television.”

In the program, Humphries says he didn’t try to be funny, it happened for him naturally. He took evident delight in making fun, and thrived on the adrenaline rush of live performance.

With Edna, he found a character that could be a vessel for his observations about Australia in the 1950s – the social lives of women and their preoccupation with the details of the suburban home.

Before then, Humphries says, “no one had thought that there was anything funny about nice suburban living, about cleanliness, about surfaces. Laminex covered everything, it even covered people’s minds … I had hit upon a wonderful vein of comedy”.

In 1956, Edna was rather plain, her hair and outfits unadorned, her voice a falsetto squawk. Over the years Edna’s dress sense became elaborate and outrageous, the “eye furniture” ever more inventive, the colour palette dialled to iridescent. And, as Humphries says, Edna’s attitudes and fashion sense evolved as she embarked on her campaign of world domination.

In the 1974 film Barry McKenzie Holds His Own, Edna and her nephew Bazza return to Australia from England and are greeted by Gough Whitlam.

As Humphries recalls: “Edna curtsied, and Gough improvised and said ‘Arise, Dame Edna’. So Edna was suddenly a dame. She claimed the Queen had given it the OK – that remains a little nebulous, this claim. Nevertheless, Dame Edna rather suited her elevated position.”

Barry McKenzie and Sir Les Patterson were the male counterweights to Edna’s grotesque matriarch. Introduced in a Private Eye comic strip, Bazza was the archetypal Australian abroad, “drowning in the moral quicksands of ’60s London”, and with a savoury manner of speech. He gave the world many choice Ockerisms including the “technicolour yawn” and “point Percy at the porcelain”.

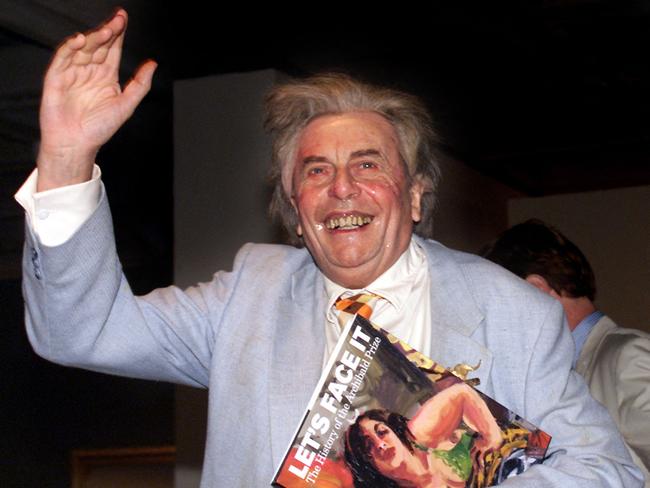

Les Patterson, with his stained suit, tombstone teeth and prodigious appendage, was invented in 1974 to introduce Dame Edna at St George Leagues Club in Sydney. Humphries’ manager at the time, Clyde Packer – brother of Kerry – told him he was missing a large part of his potential audience, which was people who went to clubs. Humphries’ remonstrated that he’d be howled off the stage if he went on as Edna.

“I decided I would introduce Edna myself by pretending to be the secretary of the club,” Humphries recalls in the ABC program.

“I had a powder-blue suit, some padding underneath it, and I called this person Les Patterson. I said, ‘I’m your club secretary. We had Liza Minnelli coming tonight, but unfortunately she’s cancelled and that’s put us in a spot. But luckily a very nice Melbourne housewife has offered to fill the gap. I want you to give her the clap she so richly deserves’.”

Humphries says Sandy Stone was his favourite creation, not least because the character – wearing a dressing gown and clutching a hot-water bottle – was always sitting down. Alexander Horace Stone, a “man of the suburbs”, first appeared in a short story Humphries wrote in the 1950s. He was the polar opposite to Edna and Les, a sibilant geriatric given to droll and meandering memories about Melbourne of the olden days.

“He told the story of his whole week, it was inevitably boring,” Humphries recalls. “I looked at it carefully to see that there was nothing that could be described as a joke – nothing humorous. I expunged all humour from this narrative, and I turned it into a monologue … Sometimes the monologue is so boring that I have difficulty staying awake on stage. I once actually fell asleep, briefly, doing this character.”

But for many around the world, Dame Edna will remain Humphries’ grandest creation, a star of her own making.

“The reason she’s a megastar is that she tells people she is, and they believe her – she thinks she’s Madonna, or something like that,” Humphries reflects. “We know she’s not – that’s the joke. What is extraordinary about the character of Edna – and I speak as though I am completely outside this character – (is) I am as it were in the wings, and she is on stage. And every now and then she says something extremely funny. I stand there and think, ‘I wish I’d thought of that’.”

Humphries has revealed the essence of his comedy. Letting people in on the joke, giving them permission to laugh. As he says: “It’s a nice job, really, to be in the cheering-up business.”

Barry Humphries in His Own Words, ABC TV, Friday, 8.30pm.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout