I remember his Gucci loafers, the rattle in his belly laugh, the rapier slash of his wit and how secretive he was about the size of his heart. Precisely how big was that warm red organ that he hid behind that devilish Dame and that glorious drunk for all those years? Big as a London theatre stage. Big as Moonee Ponds and all the rest of his beloved Melbourne.

I remember his spark. I remember his sparkle. I remember his unnecessary sympathies when I told him I was from Brisbane. I remember how he mourned the loss of the asparagus roll. It died around the same time as devils-on-horseback and Australia’s collective ability to take the piss out of itself.

And I’ll never forget this: the way he so generously downshifted the gears of his intelligence to keep conversational pace with yet another dull earthling who was sorely lacking the power of transmogrification.

Gods are always dumbing themselves down in the company of mere mortals. Barry Humphries turned toying with mortals into a televisual art form. He turned taking the piss into cultural practice. And, maybe the thing I’ll remember most about him, he turned darkness into light.

I’ve got this friend. A 1970s Queensland kid. Big Barry Humphries nut. Big fan of Barry McKenzie, aka Barrington Bradman Bing McKenzie, that incomparable comic book and film creation of Humphries who tore through stuffy London in the 1960s and ’70s, raising aristocratic eyebrows with mouthfuls of beer and boorish Australianisms that stuck to our culture like Clag: “technicolour yawn”, “point Percy at the porcelain”, “siphon the python”.

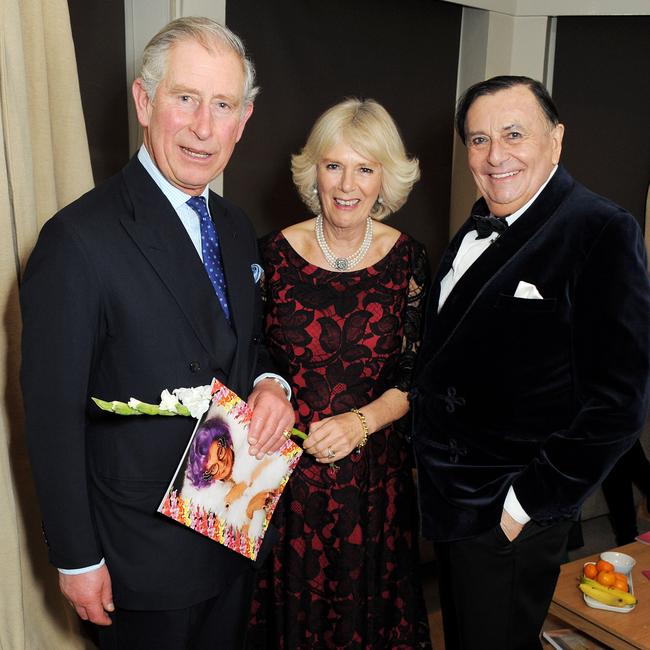

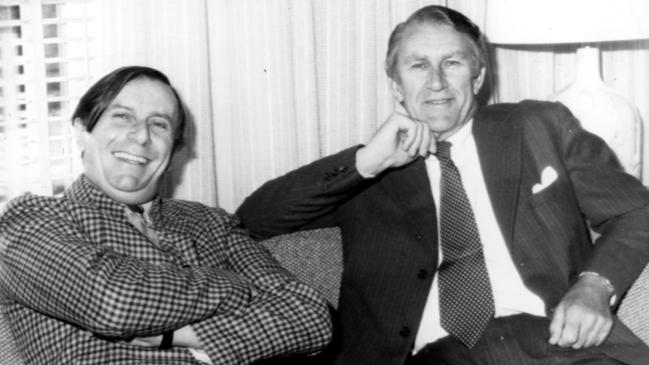

I remember the look on this friend’s face when I told him over a beer how I got to spend the best part of a day in Sydney with John Barry Humphries – AO, CBE, DSFL (Dead Set F..kin’ Legend) – for a magazine profile I was writing on Australia’s most enduring comic. He looked at me like I’d just said I’d been sipping shiraz with Jesus. Then I told my mate all the things that Barry told me that day.

He’d paid a visit to the doctor before he met me. A check-up it was. An “inside-out” one, as Barry called it. “You’ve got a few more miles yet,” the doctor told Barry, who was well into his 80s at the time. “But surely there’s something seriously wrong that I don’t know about,” Barry asked. “Nope,” the doctor said. “Something in the brain, perhaps?” Barry probed. “Nope,” the doctor said.

Then Barry leaned over to me proudly in his armchair. “The people I knew at school who excelled at sport are all dead,” he whispered.

“That’s deeply gratifying.”

That was a jab for the bullies. Barry had his share of those as a boy. That’s where Edna came from, he said. From insecurity and fear and isolation and what he told me was a lifelong “self-avoidance”.

He said he was always trying to be anybody but Barry Humphries. When he was a boy in the late-1930s, he was locked inside a cupboard by a cruel kindergarten teacher. He remembered screaming uncontrollably inside that cupboard, calling out the same name over and over. Edna. Edna. Edna.

“Edna was kind of a nanny to me,” Barry said. “A friend of the family, and she was more or less always with me as a child.”

Edna, the real-life family friend, was caring and forthright and brilliant and worldly and never scared by anything. “If only I could be more like Edna,” the boy in the darkness told himself.

So there was the big trick to it all. The big, beautiful secret. All that laughter – some 60-plus years of sequined, purple-haired, frocked-up and mocked-up joy – came from that dark and locked-up cupboard Barry Humphries kept somewhere deep inside his great big heart.

And the message from Barry was so very clear to me that day: we are allowed to turn our darkness into light. We are allowed to turn the fear that’s stuck inside our stomachs into the laughter that’s rattling out of our bellies. A truly beautiful lesson from God, for this eternally grateful earthling.