Barry Humphries obituary: there was only ever one place that felt like home for Dame Edna, Sir Les creator

Barry Humphries became tired ‘commuting’ between England and Australia, but on stage he could be ‘alone, at last’.

OBITUARY

Barry Humphries

Entertainer. Born Melbourne, February 17, 1934. Died April 22, 2023 aged 89.

Barry Humphries was such a celebrity that it’s hard to imagine him as the underground figure that haunted the precincts of the University of Melbourne in the early 1950s.

I first saw him there in the library, hard at his books like everyone else — except that his back and that of his chair rested on the floor, with his long legs up in the air. He resembled a corduroyed stick insect, but such was his imperturbability it seemed his posture was the normal one and that of the rest of us eccentric.

Humphries was already more subversive than the humourless ideologues of the Labour Club, his heroes not Marx or Lenin but the Dadaists of Zurich and Paris, Tzara and Picabia. For them and for him, the sicker the joke the better — anything to destabilise the established order.

The established order in Melbourne at the time was suffocatingly conventional, but this was the city’s great gift to him — it was the grindstone that sharpened the knives of his wit.

Humphries had the good luck to grow up in the solid brick heart of Camberwell, one of Melbourne’s most genteel suburbs. He was the spoiled first child of a father who grew prosperous as the builder of suburban villas, and of a mother who never gave up trying to make her son respectable, and whose limitless repertoire of cliches would later supply him with titles for his shows.

As the box-Brownie snaps in his memoirs show, little Barry was at his happiest when he was dressing up. The only disguise he didn’t like was the navy blue serge uniform of the exclusive Melbourne Grammar, where he had some of his early schooling (but not his education, as he was at pains to point out).

Humphries was already proving difficult. He wore his hair long (“long hair is dirty hair”, admonished his teachers) and preferred art to physical activity. “I hope you’re not turning pansy,” his headmaster said, during a discussion as to why he’d done so badly in mathematics.

The Humphries who left Melbourne Grammar was already an exhibitionist (it said so on his school report) — all he needed was an audience, and at the university he found one.

He put on a revue in which the spectators were supplied with vegetables, and after enduring the endless repetition of a tune on a piano, they used them with gusto. He mounted art exhibitions, including one called Cakescapes, which featured cream cakes, swiss rolls and lamingtons compressed between sheets of glass, which gradually went mouldy and malodorous.

The student Humphries was also a pioneer of street theatre — the more tasteless the better. He’d have an accomplice play the role of a blind cripple, who would enter a non-smoking train compartment with dark glasses and a plastered leg. Humphries, garishly dressed and puffing a noxious Turkish cigarette, would glare at his victim and, to the horror of the other passengers, rip away his glasses, kick his leg, shout “Blind pig!” in heavily accented English, and then make a hasty exit.

After two years of sending everything up, Humphries sent himself down from the university and got a job at EMI, where his main task was smashing 78 records that microgrooves were now superseding. John Sumner saved him from the business future his parents had planned for him by inviting him to join the Union Repertory Company, in which he toured Victoria absurdly miscast as Duke Orsino in Twelfth Night.

Edna Everage was conceived at the back of the bus that took them from one town to the next. To relieve the boredom while travelling, Humphries did falsetto imitations of a genteel Melbourne housewife repeating the platitudes of the country mayors as they thanked the cast for their efforts.

When the time came for the company’s annual revue, Ray Lawler, one of his fellow actors (who was tapping out Summer of the Seventeenth Doll in hotel rooms while they were touring) suggested he write a sketch for this hitherto nameless figure.

Humphries called her Edna after a childhood nanny and had her come from Moonee Ponds. But as any Melburnian would know, she was much more a Camberwell person — he changed the suburb so as not to offend his mother.

The Olympic Games were pending, so in the revue act Edna responds to a newspaper ad asking people to accommodate visiting athletes, and describes the attractions of her home in loving detail. The audience response was rapturous.

“Nobody had talked about Australian houses before,” Humphries later recalled. “I found something I could write about — not by putting a telescope to my eye but by just looking through the venetian blinds on to my own front lawn.”

However, conventional theatre life soon palled. This was only too obvious in a production of Hamlet I saw around this time, in which the irascible actor-producer Peter O’Shaughnessy played the lead. Unwisely, he’d cast Humphries as Rosencrantz. He came on stage smirking, in tights, his legs seemingly devoid of calf muscles (”On stage,” he once reflected, “my parts got smaller and smaller”) and the result was laughter, quelled only by the ferocity of Hamlet’s glare.

As well as Edna, Humphries had been developing another character, based on a Camberwell neighbour whose mundane daily routines fascinated him. He became Sandy Stone, elderly, pale and melancholy, first heard in a record called Wild Life in Suburbia, with Edna on the other side.

In 1958, both characters appeared in a revue called Rock ‘n Reel at the modest little New Theatre in Melbourne, provoking a collective hysteria of recognition and laughter. Humphries had invented a new kind of Australian humour, savage and yet affectionate — something, as he put it, the public didn’t know they needed. How, those fortunate few of us who fell about on opening night wondered, had we managed without it?

After a spell in London in the early ‘60s as the undertaker in Lionel Bart’s hit musical Oliver!, Humphries returned to his home town for a sellout season of A Nice Night’s Entertainment. This was only his second revue, but already Edna and Sandy seem determined to lead lives independent of their creator.

Success at home was followed by failure abroad. When Humphries took Edna, or Edna took him, to London’s chic Establishment Club, there was first puzzlement then an exodus to the bar. He got his revenge satirising the English in his Barry McKenzie comic strip, created, with artist Nicholas Garland, for Peter Cook’s Private Eye.

McKenzie, huge of hat and chin, wandered oblivious through the swinging ‘60s in perpetual quest of a cold Foster’s lager, sometimes voiding the vast amount he ingested on the head of a luckless Pom. When he wasn’t chundering, McKenzie talked broad colloquial Australian mixed with inspired inventions of Humphries’ own, especially to describe what his character was best at (technicolour yawn, throw the voice, laugh at the ground).

McKenzie’s drinking at the time was rivalled by his creator’s. Humphries had had a long battle with the problem, and now the problem was winning. He was committed to a psychiatric hospital, which he was allowed to leave nightly to perform in another Lionel Bart musical called Maggie May, with the strict injunction to return to the hospital afterwards — which he usually did, but only after several nightcaps on the way.

It was time to give up alcohol (at least for a while), rejoin his second wife Rosalind and his two daughters, and go home again, where he presented Excuse I at the old Theatre Royal in Sydney, in which a new character called Neil Singleton made his first appearance.

Neil was a bearded, turtle-necked, wine-buffing left-winger — and, in Humphries’ view at least, he turned the class he represented against him. The intelligentsia revelled in the mockery of characters they would never meet at their own parties, but Neil Singleton was something else, and it was then that attacks on Humphries began in what he called the “arty periodicals”.

The Edna in Excuse I had changed from a comical frump to a middle-class lady wearing the first of a series of increasingly preposterous diamante spectacles that made her look like a colour plate from Insect Wonders of Australia. The show was a huge success, and for the first time Edna rewarded her admirers with hurled gladioli, which rained down on them like arrows at Agincourt.

Just A Show, which followed three years later in 1968, introduced another character designed to irritate the arty community — Martin Agrippa, an avant-garde filmmaker, who presented a short movie of astonishing pretension (specially made for the show by Bruce Beresford).

Buoyed by Just A Show’s success, Humphries took it to London, but the reviews were tepid and the season short. To make matters worse, the queues were long outside the theatre opposite, where Ginger Rogers was performing in Mame.

In desperation, Humphries decided to capture the rival audience, if only for a few minutes. He dashed out of his own show just as the rival one was ending, and in full Edna regalia, leapt on to the roof of a parked car and did a tap routine. Two weeks later he got a hefty invoice from the car’s owner — the panel beaters had had a lot of trouble removing the indentations of stiletto heels.

If his public life was not going well, his private life was worse. He was homesick, Rosalind had given up on him, and he was drinking again — sometimes before breakfast, often unable to remember what he’d been up to the night before.

One morning, when he managed to drag himself out of bed, he noticed that his precious collection of glassware had disappeared. When he asked Roslyn, his partner at the time, whether they’d been stolen, she was incredulous — couldn’t he remember that when he’d come home late the night before, he’d thrown them all against the wall?

Humphries’ father, a generous and much put-upon man, organised his son’s rescue, and he flew back to Melbourne. But he drank on the plane, and kept on drinking, and ended up again in a psychiatric ward — this time in St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, with his father weeping at his bedside.

His career in England had petered out and Rosalind was filing for divorce. When he asked his psychiatrist what took the place of alcohol in a man’s life, he got a pithy reply: “How about gratitude and concern for others?”

“Barry is just going through a phase,” his mother was fond of saying, and the alcoholic one was now over. He gave up drinking and flew back to London, to work with Bruce Beresford on The Adventures of Barry McKenzie. He savoured the irony of a government film organisation funding a picture based on a comic strip that another government organisation (the censorship board) had once banned.

Yet another Barry — Crocker — played the lead role, which inevitably involved the absorption and expulsion of industrial quantities of alcohol. It was excoriated by the critics (Max Harris thought it “the worst Australian film ever made”) but was successful enough to warrant a sequel, Barry McKenzie Holds His Own, which some thought even worse.

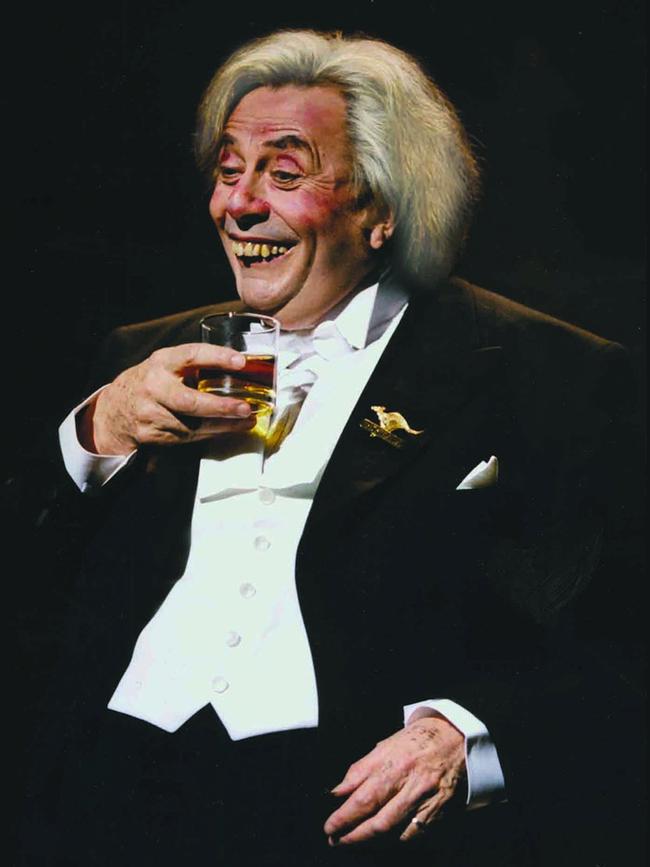

Then came his London breakthrough. Humphries adapted his last Australian revue, At Least You Can Say You’ve Seen It, rebranded it as Housewife — Superstar! and opened at the Apollo Theatre in March 1976. It had a new character who entered through the audience holding a whisky bottle — a padded grotesque in a stained powder-blue suit, with a pelvic extension that seemed to reach almost to his knee. It was Sir Leslie Colin Patterson, braying and spitting through nicotine-stained teeth: “Don’t worry ladies, Les Patterson’s saliva is safe.”

Les was a hit in both England and Australia, but not immediately in Hong Kong, where he had a short season at the exclusive Mandarin Hotel. On the first night, he hovered near the entrance to the hotel’s nightclub, waiting for his cue. When it came, the Chinese maitre d’ barred the way: “You can’t come in here. You dlunk!”

“I’m the show!” replied the dishevelled figure.

“You dlunk!”

Bouncers were summoned, there were shouts and scuffles, and only the intervention of the hotel manager got him in.

In 1979 Humphries married for the third time. His new wife was Diane Millstead, and they had two sons, Oscar and Rupert. In the ‘80s his career moved between Britain and Australia, with sellout seasons in the capitals and provincial towns of both countries.

By the ‘90s, his three greatest creations had so developed that they couldn’t live together on stage. Edna, Sir Les and Sandy Stone each had their own shows.

Edna swelled from super to megastar, and her eyewear grew with her: a vulture in bird-of-paradise clothing, as the TV producer Julian Jebb put it, terrorising not just audiences, but celebrities foolish enough to appear in her TV shows.

Sir Les had become even more gross — the teeth more carnivorous, the spittle more abundant. “He’s me,” Humphries once said, “if I’d kept on drinking.”

But Sandy has gone the other way, becoming quieter and more contemplative. I last saw him in November 1990, in he Life and Death of Sandy Stone, where he ruminates from a wheelchair after a prostatectomy. During interval he passes away, to return for the second half as a spirit, his house about to be sold, his widow Beryl travelling the world on his insurance money.

At the beginning of the show we’re laughing at him. At the end, because he’s dead and we’re safe and full of illusions in the front stalls, he’s laughing at us. It was a performance that demonstrated the truth of the poet John Betjeman’s words: “Here is no satirist. Here is a great artist.”

In the ‘90s, Humphries had only one challenge left: America. He’d failed there in 1977, but in 1999 he achieved the ultimate theatrical triumph — his Dame Edna: The Royal Tour was a Broadway hit, and ran for 10 months, disarming even the feral New York drama critics.

John Lahr, the greatest of them, wrote a book about him — Dame Edna Everage and the Rise of Western Civilisation — and Humphries received a special Tony Award for a live theatrical presentation the following year.

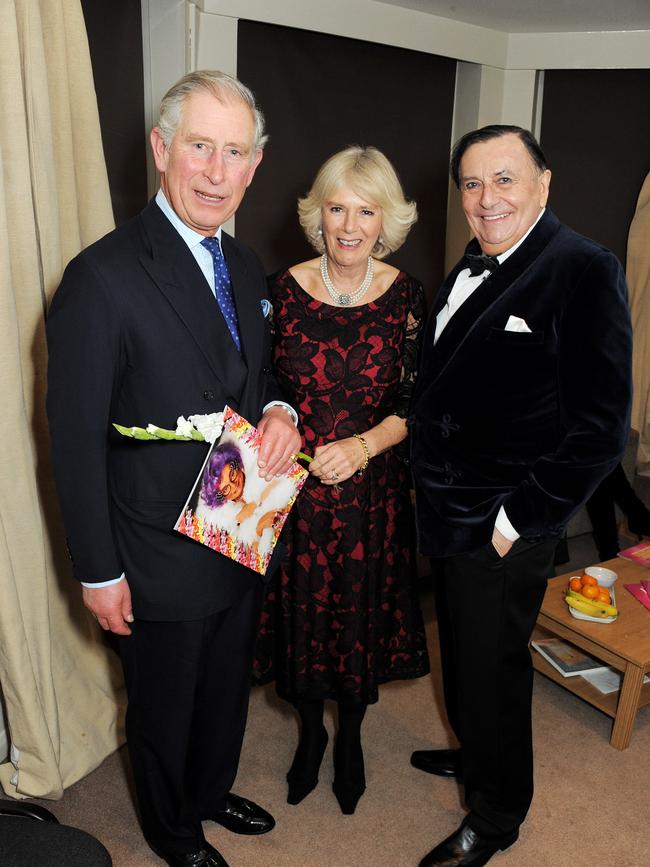

On June 4, 2002, he was one of the hosts at the royal pop concert at Buckingham Palace, and introduced Dame Edna Everage’s only serious rival — Queen Elizabeth.

Humphries was an avid collector and art enthusiast, hunting through second-hand shops and markets for vintage Australiana, French symbolist art and music of the Weimar Republic. In a 2013 with the Australian Chamber Orchestra and cabaret singer Meow Meow be brought forth a program of so-called degenerate music, condemned by the Nazis, of composers such as Kurt Weill, Paul Hindemith and Mischa Spoliansky. He’d discovered the music of 1920s Germany when, as a schoolboy in Melbourne, he came across a stack of sheet music in a second-hand bookshop, sparking a lifelong passion. A keen painter, he enjoyed friendships with Margaret Olley and John Olsen, with whom he made art expeditions to the Flinders Ranges.

Humphries gave what was billed as his Australian farewell tour in 2012 in Eat! Pray! Laugh!, which also travelled to the UK. But, Melba-like, he returned several more times to the stage. He was the artistic director of the Adelaide Cabaret Festival in 2015, where Sir Les made an appearance, and in 2019 Dame Edna, now a gigastar, returned for a national tour in My Gorgeous Life.

His last tour was in The Man Behind the Mask which he took around Britain in 2022. This time it was Humphries on stage recalling his early life in Melbourne, and with video spots from Dame Edna and Sir Les.

As well as writing his own scripts, Humphries was a prolific author, notably of his memoirs Barry Humphries: An Autobiography, and My Life As Me, from which some of the material in this obituary has been taken. Both are irresistibly entertaining, but their mannered syntax and languid ironies disguise as well as reveal. We have to peer through the persona to discern what we can of the elusive subject.

Humphries remarks in one of these books how tired he became of commuting between England and Australia, without ever quite knowing where he really belonged.

The only place where he really belonged, of course, was on the stage. “Alone at last!” he’d say to himself as he leapt from the wings. Now he enjoys his final apotheosis, and we can only look up and applaud.

Humphries leaves Lizzie Spender, his fourth wife, and children Tessa, Emily, Oscar and Rupert.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout