Siena missed the Renaissance but forged an art of unique charm and spiritual feeling

A sparkling exhibition in London celebrates Siena’s 14th century role as a centre of painting quite distinct from Renaissance Florence.

One of the most beautiful paintings in the Art Gallery of NSW is a little panel from the Sienese School attributed to Sano di Pietro, and given to the gallery by James Fairfax (or more exactly John Fairfax & Sons, of which he was not yet chairman) in 1971. It was in fact the first of many gifts of renaissance and baroque art by Fairfax during the later decades of last century that led the gallery, in happier days under Edmund Capon, to form a substantial collection of early modern painting.

The panel is a small devotional work that may once have stood on the altar of a private chapel. In the centre is the Virgin Mary, holding the Christ Child in her arms. Around this group are four saints and above them two angels. The infant Jesus turns to the left towards the first of the saints, John the Baptist, recognisable by his sunburnt complexion – as a prophet living outdoors in the wilderness – and the scroll he bears, “ecce agnus dei”, behold the lamb of God, later the formula spoken by the priest when he holds up the consecrated Host in the Mass.

Above John is Saint Jerome, identified by his cardinal’s hat, painted in bright vermilion: one of the four Fathers of the Church with Saints Ambrose, Augustine and Gregory, of whom all but Gregory lived in the last century or so of the Roman Empire. Jerome was a brilliant young scholar from Dalmatia who was first commissioned to make an official Latin translation of the New Testament, which had been composed in Greek; he then began the much longer task of translating the Old Testament from the Hellenistic Greek version, the Septuagint, before deciding that if he was serious about the task he should learn Hebrew and work from the original.

On the right side are two less familiar saints. The upper one stands out from the others as a portrait, for he was a contemporary, the hellfire preacher San Bernardino of Siena, who had died some years before this painting was made, but whose pinched features are reproduced in many works of the time; he is carrying the monogram of Christ which, in larger form, he used to hold up in his sermons. Below him is Saint Bartholomew with his attribute, the knife, for he was martyred by being flayed alive. Michelangelo includes this saint in his Last Judgement, with the features of his enemy Pietro Aretino: the flayed skin bears his own self-portrait.

The choice of these subsidiary saints is of course significant; the figure of San Bernardino would suggest the picture came from Siena, even if that was not obvious from its style. In a larger and public commission, the saints would include patron saints of the city and the church for which it was designed. In a private commission like this, the saints chosen are likely to be the patron saints of the commissioner and his family; thus here one would not be surprised if the patron’s first names were Giovanni Bartolommeo.

But all of these painted faces emerge from a shimmering background of tooled and inscribed gold leaf, and are set in an elaborate architectural frame. The whole panel represents methods and processes that are quite unlike more recent assumptions about the art of painting. We may think of Gericault struggling alone in his studio with his dark epic Raft of the Medusa; of Monet getting up at dawn and going out on the river to capture the earliest impressions of daylight; of Vincent van Gogh painting in a visionary frenzy; or of later individuals seeking inspiration in drugs or alcohol.

Nothing could be more different from the method of an artist like Sano di Pietro. In the first place, he was not a solitary painter but the master of a studio composed of apprentices and assistants. And secondly, there were many stages in the making of this work before any painting happened. First, the poplar panel had to be prepared: this meant that the timber was cut and then seasoned to ensure that it would not warp. It was planed smooth, then covered with a layer of gesso – plaster and rabbit skin glue – which was scraped and polished until it was as smooth as ivory. Next the gesso surface was painted in a red ground that enhanced and gave warmth to the subsequent layer of gold leaf. After that the position of the heads was determined and their haloes drawn with a compass; then they were incised and adorned with tooling and lettering applied with punches, like the gold lettering on the spine of a book. The Virgin’s halo, for example, is inscribed with the words ‘ave gratia plena’, hail you who are full of grace, from the angel Gabriel’s address to Mary at the start of Luke’s gospel, which subsequently became the Hail Mary prayer. The visual effect of all this elaborate tooling, we have to imagine, was to produce a coruscation of animated luminosity in the flickering candlelight of a private altar.

Only after all this did the painter finally pick up his brushes. And even then, though not necessarily in this case, he might leave subsidiary figures to his chief assistant, who had been trained to paint in the master’s style. But we can be certain that he would paint the faces of the Virgin and Child himself, for these were the most important focus of the painting, and the features on which the commissioner’s attention would be focused in his devotions. The sacred countenances had to embody gentleness, kindness and compassion, to offer hope of salvation and forgiveness for sin.

This exquisite little painting seems to express such a quintessentially medieval spiritual outlook that we may be surprised by its date, which is around the third quarter of the 15th century. It is, in other words, half a century later than Masaccio, after the death of Brunelleschi, and roughly contemporary with the great masterpieces of Piero della Francesca. Sano di Pietro’s style epitomises the way that the city of Siena deliberately turned its back on the new art of the renaissance that had begun in its great rival Florence.

If you happen to be in London in the next few weeks, the National Gallery has a magnificent exhibition – to which I alerted readers in my December roundup of new exhibitions around the world – devoted to the school of Siena, called Siena, the rise of painting (1300-1350) – which, as its date range implies, concentrates more on the emergence of the school in the 14th century than on its later and so-called “retardataire” period in the 15th. As it happens, although I was unable to get to London to see this exhibition and have to be content with its outstanding catalogue, I was in Siena itself in April leading an art tour of Umbria and Tuscany, and so had ample opportunity to ponder Sienese art again in a number of museums and churches.

The Sienese rejection of the Renaissance is probably not a strictly unique phenomenon in art history, but “retardataire” styles in other instances are due in most cases to distance from metropolitan centres or to the less dynamic nature of regional cultures. In this case, however, we have two important and prosperous cities, almost equally energetic and innovative in commercial and other spheres, and yet when one of them strikes out in a new cultural direction, the other refuses to follow.

This was not, therefore, a case of provincial backwardness, but of a deliberate and wilful determination to follow a different cultural direction, ultimately grounded in the same political and economic rivalry that led the two cities to compete with each other in the architecture of their respective cathedrals.

The difference in spirit is already manifest from the beginning of the 14th century, the period covered by the London exhibition, when Giotto begins to imagine the sacred stories set in the same earthly world in which we live our daily lives. He conceives of three-dimensional spaces, even if empirically realised since the theory of perspective was only elaborated a century later; he gives his bodies a new appearance of solidity and volume, emphasising what Bernard Berenson was later to call “tactile values”; he sets figures visibly in front of each other, forcing us to imagine them set in a spatial dimension.

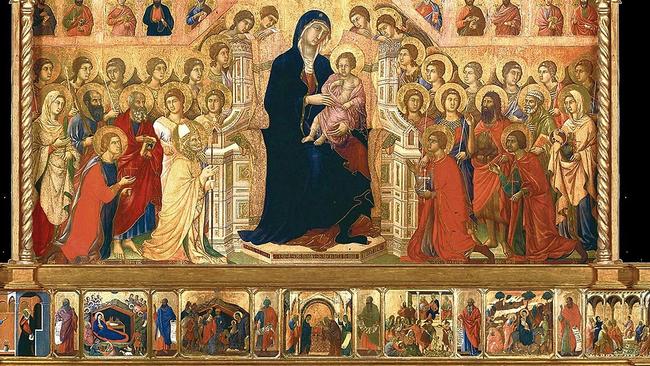

At almost the same time, the great Sienese master Duccio di Buoninsegna painted his Maesta, one of the biggest and most ambitious altarpieces ever produced. When it was completed in 1311, it was carried to the cathedral in a magnificent civic procession and installed with great ceremony. The altarpiece, sadly no longer complete today, was covered in an abundance of exquisite narrative scenes that brought the stories of Christ and the Virgin vividly to life, but in a way quite different from Giotto. Here the emphasis was not on placing the sacred figures in the world of everyday experience, but on narrating scriptural stories with inventiveness and grace and a sense of spiritual mystery.

The development of painting in Tuscany was brutally interrupted by the Black Death that broke out in the middle of the 14th century and killed between a quarter and a third of Europe’s population. The cultural energy that had arisen in the first half of the century, and which in hindsight we think of as the proto-renaissance, was temporarily crushed. By the end of the century, though, a new phase of growth was beginning, inspired by the sweet, elegant forms of the international gothic style.

Masaccio’s master, Masolino, painted in this style, but Masaccio returned to the solidity and naturalism first imagined by Giotto; as Vasari says, he was the first to paint figures standing on their feet. The best illustration of these words is in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence where I was standing with my group two months ago: on one side you can see Masolino’s Adam and Eve before the Fall, floating weightlessly on tip-toe; on the other the heavy and material bodies of Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, with Adam’s feet firmly planted on the earth which he is condemned henceforth to till to feed himself and his family.

The Sienese did not follow Masaccio any more than Giotto. Instead they borrowed elements from international gothic and combined them with vestiges preserved from the otherworldly art of Byzantium. And thus they forged an art of unique charm and spiritual feeling that has consistently delighted lovers of painting. But the price they paid for this choice was to miss the renaissance; and when Sienese art reconnects with contemporary art in the 16th century, it passes quite naturally into the self-conscious artifice of mannerism.

Siena and the rise of painting

National Gallery London to June 22

Sano di Pietro, Virgin and saints

Art Gallery of NSW

Siena and the rise of painting

National Gallery London to June 22

Sano di Pietro, Virgin and saints

Art Gallery of NSW

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout