The dark sexuality of Romantic art

There are sexual undertones even in the imaginative aspects of human experience explored in the Romantic era

Art history is divided into periods by art historians for the sake of convenience, but the resulting categories are inevitably approximate; useful if handled with tact but frustrating if we try to cling to them too tightly. Thus the concept of Baroque can be economical shorthand for a collection of tendencies, but arguments about whether the label is or is not appropriate for a given artist can often be futile. The period of Mannerism was only created a century ago to account more effectively for the decades previously thought of as either late Renaissance or early Baroque.

The period we call Romanticism is similarly complex, partly because it is as much a literary as an artistic movement, and partly because its chronology varies from one country to another. In Britain and Germany, it has its origins in the later 18th century, but in France the same generation was dominated, during the Revolution and under the Empire, by the Neoclassical style. Romanticism appears in France with the fall of Napoleon and is thus marked by the pessimism and disillusionment of the post-imperial years.

At the deepest and also the simplest level, Romanticism represents a new interest in the imaginative and irrational aspects of human experience, turning away from the Enlightenment’s faith in reason and its mechanical model of psychology, society and nature. But in that perspective, the Revolution already represents the collapse of rationalism into violence and chaos, while Napoleon himself is the epitome of the individualistic Romantic hero. Indeed it is not merely the loss of belief in rationalism that leads to the hysteria, butchery and repression of the Revolution; it is also the deeper failure of a reductive form of rationalism as theory and ideology lose touch with humanity and common reason. This is exactly the idea that Goya seems to be formulating in imaginative form in one the greatest etchings from the Caprichos series, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799): such nightmares arise not only when reason ceases to be vigilant, but when it ceases to be true reason and becomes intoxication.

Why then do we not consider David’s equestrian portrait of Bonaparte at the St Bernard Pass (1801) a Romantic painting? The answer becomes clearer if we compare it to Théodore Géricault’s An Officer of the Chasseurs (1812): it is not just that the former is more highly-finished in style and the latter more painterly, although such qualities of paint handling are expressive of profound differences of sensibility. It is also the clearer and more rhetorically assertive composition in David, compared to the complex twisting in Géricault, evoking drama but also uncertainty and doubt.

We could similarly look back on some of the Neoclassical pictures of the Empire period that were discussed last week: surely Pierre-Narcisse Guérin’s pictures of swooning youths embody the new concern for the darker regions of the human mind? And yet there is in all the work of this period a curious lack of self-awareness, which perhaps explains why these pictures could pass for the height of classical idealism when to our eyes they speak of the breakdown of rationalism under the influence of forces not yet recognised.

Romanticism, on the other hand, represents the recognition and acknowledgment of these forces, notably the sexuality which is pervasive but latent in Neoclassicism. An exemplary early painting is The Nightmare (1781), by Henry Fuseli, the adopted English painter who was born in Zurich as Heinrich Fuessli. The female figure is slumped in a state of complete surrender, while the goblin crouched on her breast is an allusion to the ancient idea of the incubus, a demonic figure who brings erotic dreams to sleeping women.

The horse’s head in the shadows on the left could be taken as a pun on the painting’s title, but horses were also natural symbols of instinctive physical energy in Romantic art. They are a recurrent motif in the work of Géricault, whose Chasseur has already been mentioned; its effective companion piece, the Wounded Cuirassier (1814). These two pictures, one painted at the height of Napoleon’s success but just before the fateful invasion of Russia, and the other after his first abdication, remind us how closely connected the art of this time can be to its political setting.

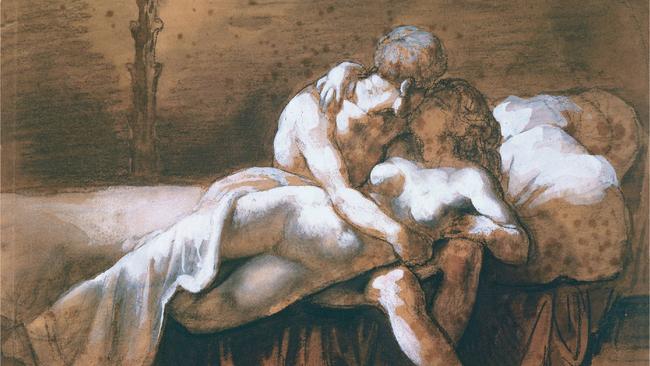

Géricault was himself a fine horseman, and it was a riding accident that led to his premature death. For several reasons, then, it is not surprising that when he was in Rome he became obsessed with the idea of painting the race of wild horses that used to be held annually in the Corso. The picture was never finished, but we have several brilliant studies of handlers struggling to control the fierce animals. At around the same time Géricault produced the charcoal, wash and gouache drawing of The Kiss (1816-17), which demonstrates what he has learned in Italy, but above all has a kind of visceral physicality that was absent from the highly-finished and rather etiolated figures of the Neoclassical painters. A little later he painted The Three Lovers (1817-20), which is unusual in depicting a trio of lovers, with a still-dressed girl who has come to join the couple in bed.

The scene is not only far earthier and more sensual than the Neoclassical pictures, but also more naturalistic, like a memory of something actually experienced, than the dreamlike erotic images of Rococo art. In contrast to these images, Géricault’s one great work, The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), has notes of eroticism only in the young male nudes; two of these are dead or dying, but they still have a far more vivid sense of corporeality than Guérin’s languid Morpheus.

The model for one of these young men – the figure on the right – was Géricault’s fellow pupil in Guérin’s atelier, Eugène Delacroix, who would become the leading French Romantic painter until his death in 1863. Delacroix was most probably the natural son of Prince Talleyrand, the brilliant statesman who managed to flourish under the Revolution, the Empire and the Restoration.

Delacroix made his first appearance at the Salon with The Barque of Dante (1822), which was mentioned in the first piece in this series. A few years later, with The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), he produced the quintessential expression of the twin Romantic obsessions with sex and death. The composition was inspired by Lord Byron’s play Sardanapalus (1821), at a time when Byron was a literary superstar and when young French artists were turning to English literature for inspiration, including to Shakespeare, whom they discovered for the first time.

Byron’s play purports to tell the story of the last Assyrian king, before his defeat by the Neo-Babylonians in the 7th century BC, a hundred years before the conquests of Cyrus the Great. Sardanapalus is wildly indulgent and decadent, dressing in women’s clothes and served by lovers of both sexes, until with the enemy at the gates of Nineveh, he orders his funeral pyre to be prepared and burns himself with his treasures, his horses and his favourite attendants. The story, although based on ancient sources, is apocryphal and there was no Assyrian king called Sardanapalus, but this does not detract from the extravaganza of an exuberant painting in which the king lies brooding at the top of his pyre while in the foreground a beautiful slave girl is about to have her throat cut and on the left a magnificent horse – a Romantic motif as we have seen – is brought in to be slaughtered.

But Delacroix also employs erotic motifs in the service of political themes, notably in The Massacre at Chios (1824). The Greek War of Independence had begun in 1821, and their cause attracted enormous sympathy in the west, especially after the massive resurgence of neo-Hellenism that I mentioned last week; Byron himself went to help fight the occupying Turks and died at Missolonghi in 1824.

The occasion of this picture was an Ottoman atrocity on the island of Chios in 1822, when more than 50,000 civilians had been murdered. Outrage at this massacre helped to provoke the western powers to intervene; the Royal Navy sank the Ottoman fleet at Navarino Bay in 1827 and by 1828 French troops had helped drive the Turks out of the central areas of Greece.

Delacroix shows a group of the Greek victims including a dispirited man with his wife leaning on his shoulder, a dead or dying mother with an infant on her breast, a motif that goes back to Poussin’s Plague of Ashdod (1630), beyond that to Raphael’s engraving of the Morbetto (1515-16) and ultimately to a lost painting by Aristides mentioned by Pliny the Elder (Natural History 35.38). On the right is a female nude whose own artistic lineage goes back to Andromeda chained to the rock; here, however, she is a captive being carried off by a Turkish soldier on horseback. Thus the theme and even the iconography of bound beauty are borrowed and politicised by Delacroix: she no longer evokes merely a certain erotic sensibility, but alludes plainly, if still decorously, to the harsh reality of the rape and enslavement of Greek women by Ottoman troops.

Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) is so familiar that we can forget what an unusual and original composition it really is. It was painted during the Paris uprisings in 1830 which overthrew Charles X, the younger brother of the unfortunate Louis XVI and brought his cousin Louis-Philippe to the throne with the promise of ruling as a constitutional monarch on the British model. This looks like a contemporary history painting, but it is more accurately considered as an allegory. Delacroix wants to show that all classes are united in their demands for liberty, so he is careful to include naturalistic details of costume to make this clear. Even the central figure of Liberty carries a flag and a rifle with bayonet fixed and appears to be wearing a more or less modern dress.

With her Phrygian bonnet, however, inherited from Marianne as the revolutionary personification of the republic, there is no doubt she is a symbolic figure rather than a real woman. Her bare breasts too allude to her ideal nature, recalling the long tradition of representing abstract concepts as female figures. But there is an even more specific allusion to the statue of the Venus de Milo, which had only been discovered 10 years earlier in 1820.

In adopting the attitude and semi-nudity of what became the most famous ancient statue in France, Delacroix imbues his allegory of Liberty with the prestige of antiquity and reminds us of the origins of the very idea of democracy in the ancient world. But he also enlists eros and Venus herself in the revolutionary cause: under Liberty’s leadership, freedom becomes an object not only of aspiration, but of desire.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout