China’s extreme lockdown measures could cripple Australia

China’s harsh lockdown in response to its Omicron outbreak is coming at a cost to the rest of the world. And that includes Australia.

As one looks at the events unfolding in China, you could be forgiven for thinking that we had collectively travelled back in time to the dark days of February and March 2020, when China sent its cities into the world’s first 21st century lockdown.

Despite most countries now attempting to live with the Covid-19 virus, in China, Beijing’s strategy of Covid-zero, or near zero tolerance for the spread of the virus, remains its fallback position in its response to the virus.

Heart-wrenching video of a worker in Shanghai, who stops a truck to expose his desperation and hunger. Man breaks down crying when given bananas and crackers pic.twitter.com/trNTM9vHzi

— Chuang (@chuangcn) May 3, 2022

While the vast majority of the world has engaged in lockdowns and other measures, China has gained a well-deserved reputation for the most draconian lockdowns in the world.

Recent scenes in Shanghai of people being fenced into their homes and apartment complexes rammed home the fact that Beijing is well and truly committed to attempting to contain the virus.

And while these containment measures have enjoyed success in the past, they come at a major cost – to both the people subjected to them and the Chinese economy.

Supply chain crisis 2.0

Perhaps one of the best examples of the link between China’s lockdowns and the impact on global supply chains is the mega metropolis of Shanghai. Since late March, the city has been in varying degrees of lockdown, with the city’s 26 million people largely confined to their homes for several weeks.

It didn’t take long for the impact to be felt on supply chains. In just days, the number of ships waiting for a berth at the port of Shanghai began to rocket. As of May 3, 344 container ships were waiting to dock.

To put this figure into perspective, the combined number of container ships waiting to dock at the two busiest ports in the United States (Los Angeles and Long Beach) during the peak of the US supply chain crisis was around 100.

As a result of China’s lockdown and other factors, congestion and delays have butterflied out to impact major ports around the globe.

According to a recent study by analysts at the Royal Bank of Canada, roughly one in five vessels in the global container ship fleet was currently stuck in congestion at a major port.

At the start of 2020, it took 51.1 days for a shipment to go from the factory gate of a manufacturer in China to travel to the warehouse of a distributor in the United States. By mid-April that figure had risen by 117 per cent to 111.3 days according to global logistics platform Flexport.

Global supply chain's returning to normal?

— Avid Commentator 🇦🇺 (@AvidCommentator) May 5, 2022

Not so much, even before the recent lockdowns in China pic.twitter.com/j6XtQ9GKXU

Considering that pretty much everything with a ‘Made In China’ label on it is being impacted in one way or another by the ongoing lockdowns, delays are commonplace and shortages in some products may result.

While Australian industry and retailers have done their best to cope with the challenges that supply chain issues have thrown at them, this additional hurdle will create further problems later in the year, as delayed shipments and production begin to feed into their inventories.

More inflationary pressures

Over the past 18 months, Australians have had quite the education in the reality of supply chain-driven inflation along with pretty much everyone else in the world. In short, if disruptions to transport or manufacturing occur to the point where there is insufficient supply to meet demand, prices rise.

With inflation currently sitting at 5.1 per cent, its highest level in more than two decades, further inflationary pressures stemming from lockdowns in China would present a further challenge for households. Meanwhile in Australia, after already having our first interest rate rise in more than 11 years, further upward pressure on inflation could drive the Reserve Bank to consider raising interest rates more rapidly than they are currently planning to.

In a recent article for Chinese Communist Party publication Study Times, Chinese Health Minister Ma Xiaowei committed to maintaining Beijing’s “dynamic zero-Covid” policy and urged the country to take a clear-cut stand against thoughts of “coexisting with the virus”. He went on to rule out any relaxation of restrictions ahead of the Communist Party Congress in October.

With more than five months remaining until the Congress, Australia and the world may continue to face inflationary pressures as a result of supply chain issues driven by Beijing’s Covid-zero strategy until the end of the year and potentially beyond.

A blow to a slowing global economy

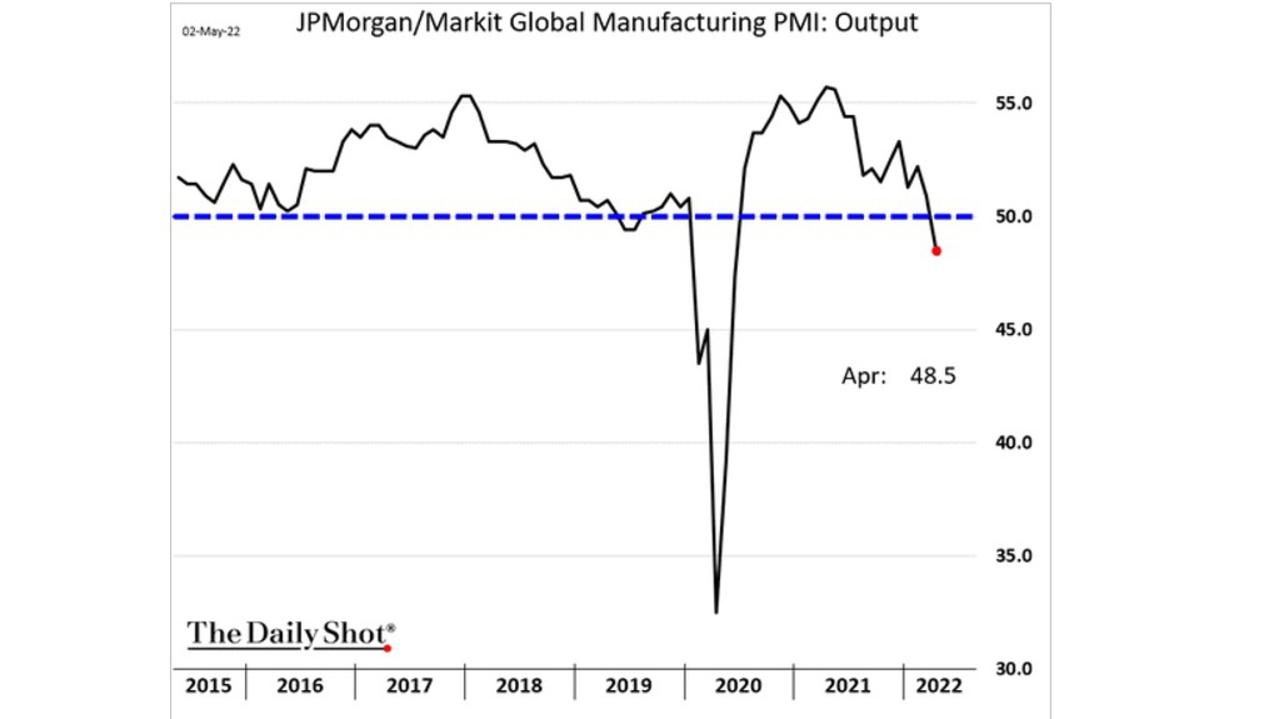

Earlier this week it was revealed that global manufacturing output had fallen for the first time since the early days of the pandemic. While a major factor in the fall in output was driven by the impact of lockdowns on the Chinese manufacturing sector, it’s just one part of an increasingly challenging puzzle.

In Europe, a recession is an increasingly real possibility, as the impact of government stimulus fades and rising energy costs take their toll on households and businesses.

In the US, key manufacturing data releases such as the ISM Purchasing Managers Index recently revealed weakening growth within the sector and employment on the borderline of a potential fall.

While headline Australian economic data such as GDP growth and unemployment are still performing strongly, behind the headline data points, the picture is already quite a bit more challenging for Aussie households.

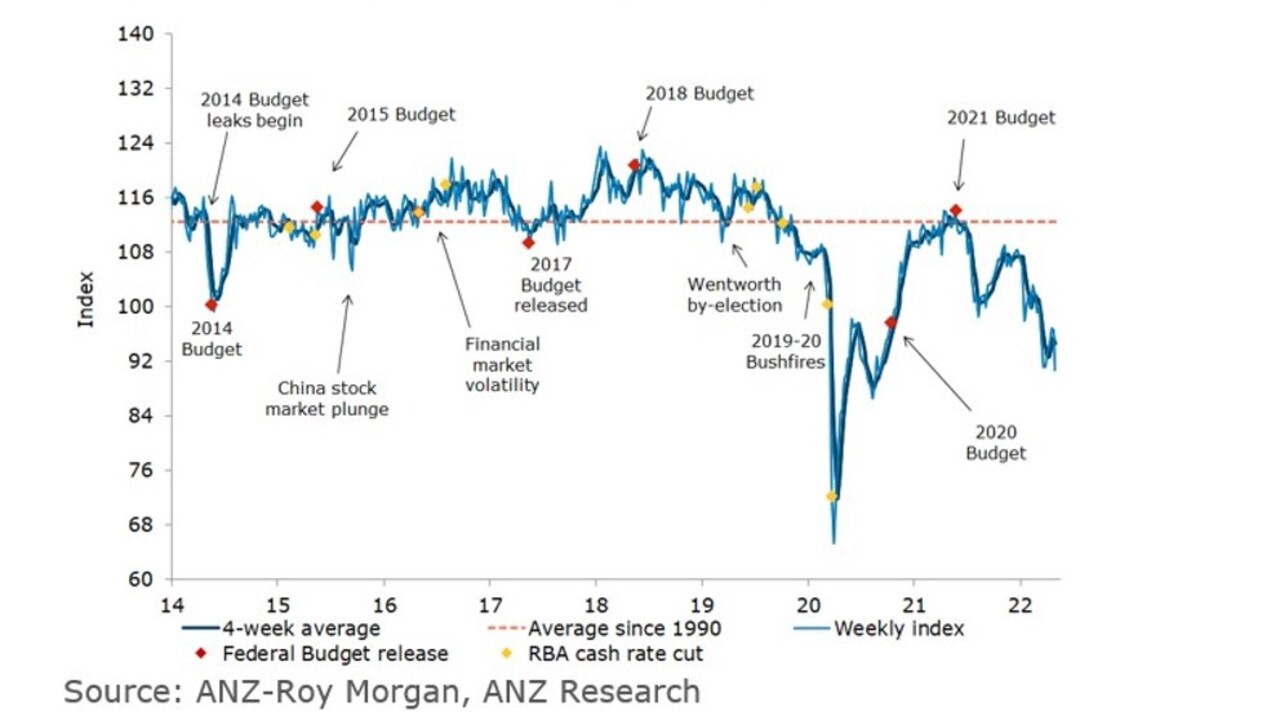

Wages growth is going backwards in inflation-adjusted terms, there is a looming housing crisis as the RBA is expected to implement a series of interest rate rises, and consumer confidence remains very weak according to ANZ’s weekly survey.

It all points to the fact that Australia would not be immune to a global economic slowdown.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator. | @AvidCommentator