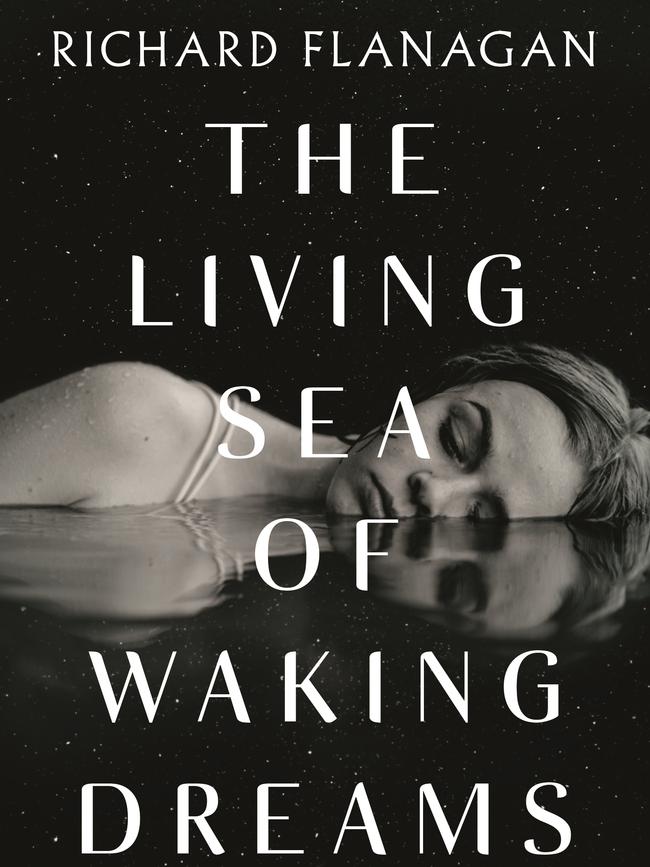

Burnt skies and island backdrop to Richard Flanagan’s new novel The Living Sea of Waking Dreams

Fire, smoke, confusion – an island at unrest sets the scene for a dramatic new novel of death, disaster and family by Man Booker Prize-winning author Richard Flanagan. WATCH AUTHOR’S WISE WORDS >>

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It would make a corny scene in a novel, but it is a golden moment in an interview with Richard Flanagan when a woman at the next table pulls one of his books out of her bag to read over coffee.

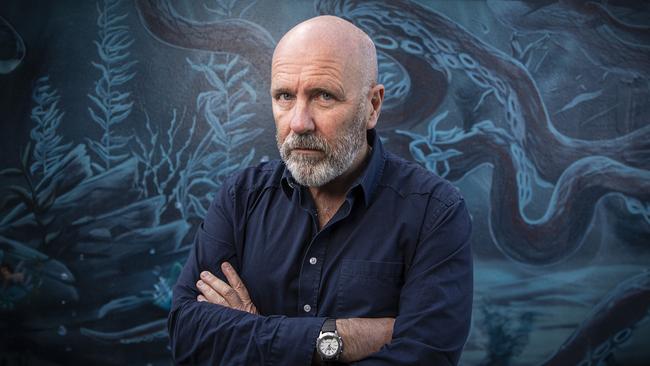

The famous Tasmanian author is a regular at the North Hobart cafe and we’ve snagged his favourite spot outside. As the young woman settles in with an old paperback copy of Flanagan’s 2001 novel, Gould’s Book of Fish, the man himself poses for photographs across the road in front of a seascape mural. It’s a fitting backdrop for portraiture on the day his eighth novel, The Living Sea of Waking Dreams, is released.

Kaja, a Czech scientist living in Tasmania, says she is not far into Gould’s, Flanagan’s third novel, but so far so good. She expects his 2014 Man Booker Prize-winning sixth novel will be hard to beat.

“Nothing will trump The Deep North, the one with The Deep – The Road to the North or something … The Narrow Road to the Deep North,” she says, finally hitting on the correct title. “It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read. The tragedy of it. Lost love, what could have been.”

When Kaja learns Flanagan will be here in a minute her eyes widen. Right on cue in a morning chockers with publicity obligations, he appears with a flash of piercing blue eyes and a jocular charm that segues smoothly into seriousness. After inscribing Kaja’s book, he asks if she likes the work of the late Czech novelist Bohumil Hrabal. She does.

Flanagan chooses memorable titles for his books, notwithstanding the tendency of The Narrow Road to the Deep North to trip up readers. The blunt title of his debut novel, Death of a River Guide (1994), a story set beneath a waterfall on the Franklin, is oddly compelling. The Sound of One Hand Clapping (1997), exploring intergenerational trauma among post-World War II central European immigrants working on Tasmania’s hydro scheme, draws its perplexing title from a philosophical Zen riddle. Gould’s Book of Fish, his third novel, is subtitled A Novel in Twelve Fish. Then there’s The Unknown Terrorist (2006), Wanting (2008), and, following his Man Booker Prize winner, First Person (2017).

And so to The Living Sea of Waking Dreams. Flanagan drew the title from the poem I Am! by 19th century poet John Clare, the son of a farm worker who wrote about the English countryside and his distress at seeing agrarian customs disrupted when communal land was usurped by private ownership.

“What had been old rights of gathering, gleaning and hunting became crimes of trespass and scavenging,” Flanagan says.

“All these places sacred in his world were destroyed. And as they collapsed, he lost some central anchor to his own personality and he went mad and spent his last few decades in an asylum, where I Am! was written.”

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams came to Flanagan through waking dreams, his imagination roaming like those pastoral gatherers of old. And it came to him as a scream: an imperative to respond to the distress he felt within and around him.

“I had written another novel,” he says. “It was quite advanced, but I felt a rising shriek in me that I couldn’t give tongue or throat to. The novel I was working on wasn’t able to express what I was feeling. There were things I was witnessing that I found deeply distressing.”

Loss has always been a theme in Flanagan’s work – and his firebrand environmental campaigning – but galloping climate change deepened his unease. Society’s distractibility via digital devices made the loss proposition more frightening: what if, in their inattention, people did not notice or care what was lost?

Then came the Tasmanian bushfires of early 2019, when dry lightning strikes contributed to almost 100,000ha of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area burning, and more than that again in other parts of the state.

“During the Tasmanian fires everything came to a head and you could see that we were now facing a moment of immense loss and that we are truly in the autumn of things,” Flanagan says.

“My difficulty as a writer was finding a language that would speak both of this immense loss and this grief that a lot of people feel, and at the same time speak of possibility and hope.”

It was on Maatsuyker Island, 5km off Tasmania’s south coast, that Flanagan found the voice that carries The Living Sea of Waking Dreams.

“At the height of the bushfires I went down there on a cray boat and was violently ill for about 18 hours getting there,” he says with a laugh.

“I was very pleased when I finally arrived. It is a place I’ve always wanted to visit and it really is extraordinarily beautiful.”

Staying with friends who were volunteering as lighthouse keepers, each morning he walked to a weather observation hut above the caretaker’s cottage to write.

His plan was to continue his work in progress.

“But what became the first chapter of this novel just poured out of me,” he says. “I had wanted a fable and I’d had this idea of a middle-aged woman who was losing parts of her body, but suddenly I had the voice and I had the story.”

The narrative is carried by a successful Sydney architect, Anna, whose mother Francie is dying in Hobart, necessitating her daughter’s more frequent trips home to Tasmania – not without resentment over the interruptions to her busy life.

Anna’s brother Terzo, a venture capitalist, also sweeps into town intermittently, taking charge of the family. Both view their sibling Tommy as a bit of a loser and find themselves unable to muster any gratitude for his care of their mother over the years. Another brother, Ronnie, the golden child, who died by suicide, reappears in family members’ dreams.

At first, it seems the siblings have gathered to see their mother out, but they swerve off course, pulling out all stops and pressing all their high-level contacts into service to keep the dying woman alive, relegating Francie to a living hell.

The seed was sown when one of Flanagan’s three daughters, who works in a hospital, told him about a wealthy family that was trying to keep an elderly mother alive at all costs.

“The mother was brought in and she was ready to die and she wanted to die and her children wouldn’t let her because somehow it offended their sense of power and wealth, so they used that power and wealth to ensure she didn’t die,” Flanagan relates. “I thought, ‘Why would people do that?’ So I invented the family.

“It is driven by a middle-aged woman because no one much honours middle-aged women, either. They are sort of erased at a certain age. They start to vanish. I wanted to join all those things together and see where it led.”

Not long in, Anna starts losing parts of herself – first a finger, then another finger, a knee, a breast … She feels no pain, only absence, as well as a troubling realisation that nobody notices. The curious phenomenon feels more sinister when Anna’s son, addicted to his gaming console and holed up in a darkened bedroom, also begins to vanish incrementally.

“I mean, it’s a comic story,” Flanagan says. “But to make that element of fable work, it has to be deeply rooted in something concrete. The reality of the hospital helped anchor the absurdity.”

The novel’s magic realist, or metaphysical, dimension in turn illuminates aspects of a disconcerting era.

“Reality is so strange now that the least realistic way of describing it is realism,” Flanagan says. “You need strange stories to rip the cataracts off people’s eyes and allow them to see anew what the world really is.”

After the Tasmanian bushfires, Flanagan set himself an ominous deadline, writing at a furious pace last year.

“By autumn it was clear the summer we were going to have on mainland Australia,” he says. “Even a fool of a novelist in Tasmania could see that it was going to be terrible.

“We had a profound premonition of it because all the same things had happened to us, including the dry lightning strikes starting fires in the rainforest. So my idea was I would sketch the novel out and have it roughly ready and then I would rewrite it in real time last summer, and I would let whatever happened infuse the novel.”

Black Summer is conveyed mostly through the prism of Anna’s mobile phone, which she checks obsessively with its relentless real-time updates of catastrophic destruction. With 18.6 million hectares aflame, animal deaths skyrocket to almost unfathomable billions, with some species believed to have been driven to extinction.

Still, Anna pauses to post a picture of her new shoes.

Flanagan does not engage on social media.

“I never have, which actually led to some severe factual errors [in the manuscript],” he says, chuckling. “I constantly went to my daughters to ask ‘How does Instagram work?’ and dreadful questions like that.”

Despite his obvious misgivings, he says the book is not a judgment on social media, just an observation of how people retreat into it.

“We live in such an extraordinary moment in history that you point to what’s happening, then you just point back at your phone, because it’s too much for any of us to try to see afresh exactly what is in front of us.

“We refuse the evidence of our lives.”

Flanagan drew on poet Clare again for the novel’s epigraph, which begins “To the axe of the spoiler and self-interest fell a prey …” from the poem Remembrances.

“We are going through a period that is disturbingly similar in crucial ways to the period Clare describes, but it is even more alarming,” Flanagan says.

Typically for an author who began as a historian, whose work is intrinsically place-based – on a globally peripheral island – and whose abiding concerns have driven him out of his writing room and on to conservation podiums over many years, Flanagan draws on home territory to illustrate his point.

“Just here in Tasmania we are seeing our seas, which were our great commons – Tasmanians are a great boat and water people – being privatised by the fish farms,” he says.

“They are basically being taken from us … and people feel this as a great loss. It is not just an environmental concern. So many Tasmanians feel this is something that’s being stolen from them.”

His eyes flick towards the east to locate the city fringe hillside, with its myriad sporting centres and remnant bushland pockets, where he lives at the Glebe with his Slovenian-born wife Majda.

“Just over there on the Domain are [among] the last of the swift parrots. We might have them for another decade and a half unless we do something. Where I go [to our shack] on Bruny Island to write are the last of the forty-spotted pardalote. They may have a decade and a half left.”

He returns to the ocean. “A few bays from here we have had the first fish in modern history to be declared extinct a few months ago,” he says of the smooth handfish, with several other handfish species, including spotted, red, and Ziebell’s, critically endangered through habitat destruction and loss, pollution and changing climate.

“These things are warnings to us and I felt at once such a sadness that these are things my grandchildren will never know, but I also thought there was something about the beauty of the world that deserves to be honoured and that people should honour it with gratitude.

“People don’t acknowledge how beautiful and extraordinary the world is and if they could just see the strangeness of our times for what it is, and see the beauty of the world for what it is, then perhaps some hope is possible. And I wanted to write in a spirit of kindness and gratitude.”

In the novel, themes of loss, erasure and extinction develop as the siblings redouble their efforts to keep an emaciated and pain-ridden Francie alive, cloaking their fear with performative acts of “love”. Readers of William Faulkner may twig, when a dray appears in a dream, to a gentle allusion drawn between Francie and Addie Bundren, the matriarch from As I Lay Dying, and her children.

Big questions hover throughout. What happens to us – as individual offspring, as families and as societies – when we lose our elders, not just to death but to relegation?

Flanagan says that whenever he visits Central Australia’s Gibson Desert for a book he is researching on one of the Pintupi Nine artists (a splinter group of Aboriginal people who lived nomadically and completely outside Western civilisation until 1984) he is struck by the respect shown to older people.

“Older people are seen to be a source of leadership, something that solidifies a community with wisdom and stories. They are seen as necessary to hold the society together, and we have the opposite ideas take hold. We are terrified because we no longer know how to live, so we no longer know how to die, so as people approach that time we seek to make them disappear.

“It struck me as a very strange thing to do … it seemed to me there are things about a vanishing world [that are connected] to what we do to old people.”

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams is despairing, but not just that. Hope is embodied in individual choices and actions. Love is celebrated: Francie is both a vessel and an emanation of love.

Flanagan’s depiction of mother love is so beautiful and moving you just know he must have basked in its glow – and returned the warmth in kind.

The fifth of six Flanagan children, Richard was born in 1961 and grew up in the West Coast mining town of Rosebery, where his father Arch was a primary school teacher and former prisoner of war who slaved on the Thai-Burma Railway, an experience the author drew on for The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Stories reveal Flanagan’s mother Helen as quite the benign matriarch, vibrant personality and prolific letter writer. Both parents lived well into their nineties, Arch dying on the day Flanagan sent his Narrow Road manuscript to the publisher in 2013, and Helen the following year.

“For the death of Francie, I drew on things about my mother, but my mother’s death was very different because our families are quite different,” says Flanagan. “Ours is very Tasmanian, which is to say clannish.”

When Helen was dying over three or four days, he says, many people came to say goodbye and at times there were dozens of people in the corridor and antechamber waiting for their turn to come in.

“It was the most extraordinary thing,” Flanagan says.

“It will sound strange, but it was in her case true, that it was one of the most affecting and beautiful things I’ve seen in my life, her death.

“One by one each person would go up and they’d have to get in very close because she didn’t have much strength and to each person she would say something apposite and beautiful that they sort of treasured. And her final words were ‘Thank you all for coming. I’ve had a lovely time’.

“I’d never thought that you can have a good death, but I suddenly understood that if you accept life, you accept death, and you can do it with grace.”