A sabotaged mother stars in Lohrey’s hostage drama

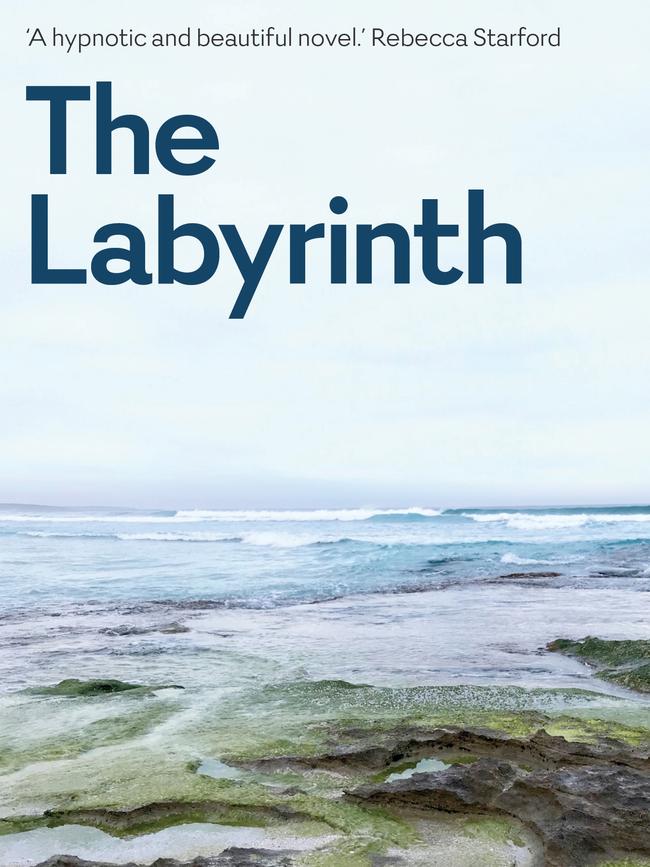

Amanda Lohrey explores emotional hijacking between parents and adult children in her new novel, The Labyrinth. WATCH THE LABYRINTH VIDEO >>

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Parenting can be a lifelong maelstrom, says novelist Amanda Lohrey.

“There’s a possibility of ambush at every moment. Things might be going along beautifully and then your 50-year-old son has a stroke.

“My mother is 93 and she is still fretting about her children. It never ends.”

Emotional hijack — rather than physical catastrophe — is what the multi-award-winning Tasmanian author explores in her latest novel.

Lohrey places her protagonist, Erica Marsden, in a seaside hamlet not far from the jail where her son and only child Daniel is imprisoned for a crime that left five people dead.

Their fraught relationship compounds her grief and anguish.

It’s a pleasant enough little coastal settlement and the shack she buys is comfortable enough, but Erica’s position is almost inescapably bleak in relation to her son.

Or so it seems in the book’s first half, which is the point I’m at when I interview the author at Salamanca.

Lohrey and her husband Andrew live at Falmouth on the East Coast but are on an extended visit to Hobart, having taken advantage of this year’s more affordable rental accommodation to spend more time with their daughter and grandchildren in the city.

Lohrey’s steady gaze is penetrating beneath her trademark white fringe.

Amanda Lohrey’s latest protagonist must contend with a disturbed son jailed on a life sentence. Picture: RICHARD BUGG

In her keen focus, she takes every thread of conversation to a more interesting place.

“It does cheer up towards the end,” she says of The Labyrinth with a laugh.

It’s hard to imagine how, I say. It would take Houdini-level emotional acrobatics for Erica to extradicate herself and find any measure of freedom.

“Since my past and my future were hitched to my son’s life sentence, I felt that if I stepped outside the present I risked being turned to stone,” Erica says.

Her grief is complicated and unremitting. In its thrall, she exists minimally in her humble beach shack. Flat moods and creeping dread cast a pall over her days.

Only when Erica fixates on the idea of building a labyrinth does the stranglehold begin to loosen.

“Now, at night, I pore over dozens of patterns, hundreds if you include the variations in materials. At first I went online to see what I could find but the net is a labyrinth of its own, a flashing series of messages, an echo chamber of disembodied voices that leaves me adrift and unsatisfied. These are the moments when my activity seems preposterous, a deluded attempt at distraction, nutty and futile.”

Lohrey became interested in labyrinths when she noticed them popping up all over the place, including in hospitals and prisons and in farms and gardens.

In Australia, one of her favourites is in Canberra at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture.

Its gardens are home to several spiritual designs, including a simple labyrinth formed with native plants and gravel pathways. At the centre is an ancient rock from the Kimberley.

Lohrey says her experience there moved her more deeply than her visit to the famous labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral in France.

“Walking that simple little natural labyrinth, sitting on this rock that’s nearly as old as the planet and looking out over the hill, that’s a bit of a buzz, that’s a bit of an experience,” she says.

“I found it a lot more affecting than the Chartres one, which is very paved and very perfect. I never like things that are too perfect.”

Lohrey found herself wondering what was behind the seeming proliferation of labyrinths, which are essentially ancient walking mandalas said to bring forth wholeness through ritual progression.

“The only thing I could think of was that people lack ritual in their lives,” she says. “They don’t go to church. It’s a kind of secular ritual and mindful meditation that they do, and there’s also something archetypal in the pattern.”

There is a difference between a maze and a labyrinth, Lohrey says, sounding a lot like Erica during an early, obsessive phase of her research.

“A maze is a puzzle where you can get lost. There’s a lot of dead ends and so it’s a challenge to the intellect and the memory. A labyrinth is more a matter of the heart.

“It’s one path. You can’t get lost, but it doubles back on itself all the time, so you have to just surrender and walk it in a fairly meditative state. When you get to the centre you sit for a while and meditate, if you like — or if you’re impatient like me you often just walk right back out.”

There’s a mystical element to labyrinths in various cultures.

“Scandinavian fishermen used to put them by the coast and walk them to ward off dangerous winds,” Lohrey says. “Well, that’s just magical thinking. Hindu midwives used to get the woman to mentally walk a labyrinth in childbirth as a way of dealing with the pain, which I must say wouldn’t have worked for me, but anyway …”

The novel is set in and south of Sydney, where Erica’s shack is an easy drive to the inland prison where Daniel is held on a life sentence, but Tasmanian readers will recognise some familiar places here, too, including the setting of Erica’s childhood within the compound of a psychiatric institution. Nominally, this “manicured madhouse” is Melton Park, but it will ring bells for anyone who has visited the former mental asylum Willow Court at New Norfolk in the Derwent Valley.

It’s the internal landscape and journey, and the space held by relationships, that are Lohrey’s driving concerns. Her storytelling is masterful: honed to pleasing plainness and assured in its measured tempo, her novels would take multiple readings to unpick her craft, which is deft to the point of invisibility at times. In other words she makes what is very difficult to achieve look easy to attain. Luckily for a host of younger writers, she has shared her gift over decades not only by writing books but by teaching subjects including creative writing at various Australian universities.

Lohrey’s previous novels include Reading Madame Bovary, Camille’s Bread, The Morality of Gentlemen and Vertigo — in which a couple of young sea-changers move to Garra Nalla, the same place Erica moves to in The Labyrinth.

It is not just Erica’s relationship with her son in the wake of his crime that Lohrey writes about. Other familial relationships are explored, including prolonged parental absence. Erica’s mother ran away the week before her 10th birthday, never to return; and she is punished by Daniel for his father’s absence.

“The hatred of the mother who is not enough, who is not the longed-for father.”

E rica needs help to build her garden labyrinth, which is how an itinerant stonemason enters her life and home. The mysterious young man is far from his home, having distanced himself from the bonds of a troubled relationship with an angry father.

A local girl helps Erica with housework and sometimes brings her little brother along to play, triggering Erica’s memories of childhood closeness with her sibling Axel, from whom she is now estranged.

An overarching question in the book is whether or not solace and redemption can be attained through making and building.

Like psychoanalyst Carl Jung, whom he otherwise disparaged, Erica’s psychiatrist father believed making things was a healing process. He had set up a workshop and craft studio for patients at Melton Park.

“ … he believed in the mind as a divine engineering project designed for the invention and use of tools,” says Erica.

“Homo faber: man the maker. The use of the hands is a powerful medicine, he would say. We can succumb to the temptation to overthink a problem when the cure for many ills is to make something.”

If Erica Marsden is somewhat impractical, the author says she is immensely so. “That’s part of the fascination,” Lohrey says.

“I was the only person in my school who was ever expelled from the sewing class. I’m extremely impractical. Seriously. I’m in awe of people who can build things and make things … I can’t knit. And when I am looking after my grandchildren, well, if I have to help with Lego, my five-year-old grandson has a better spatial sense.

“That’s why I don’t drive. I have no spatial sense … I would just be a menace on the roads.

“Also I grew up in Hobart, where you can walk everywhere. Had I grown up in the Outback, I’m sure I would have learnt to drive. Or if I’d had two children, not one…”

With her accommodating husband chauffeur on hand and rarely prone to stir-craziness, Lohrey says she’s never felt the need to be behind the wheel. She is at peace as a passenger.

“Writers spend so much time alone in a room with a computer that they’re not the most sociable of people, anyway … The urge to jump in a car and just take off rarely hits me.”

Conversely, the urge to write barely leaves her, and she finds the process more mystifying than ever.

“You are working blind a lot of the time, then the editorial part of you comes in and thinks this scene is undercooked, it hasn’t got where it needed to go or it’s out of focus.

“These are all metaphors for saying you don’t know what you are doing, but you know it when you see it. I did many, many drafts of this novel.”

She laughs again. “I wish I could account for myself, but I can’t. And I think the older you get as a writer the less you know why you’re doing what you’re doing. You’d think it would be the reverse.”

She jumps to her work in progress. “I am fascinated by all these [decommissioned] churches for sale [in Tasmania] and I’m doing a novel now about a woman who buys a church to convert it into a house.

“Again, it’s a practical project I could never manage.”

When it comes to writing, though, she trusts the labyrinthine process. •

The Labyrinth,

Text Publishing, $29.99