TasWeekend: Love in a troubled climate

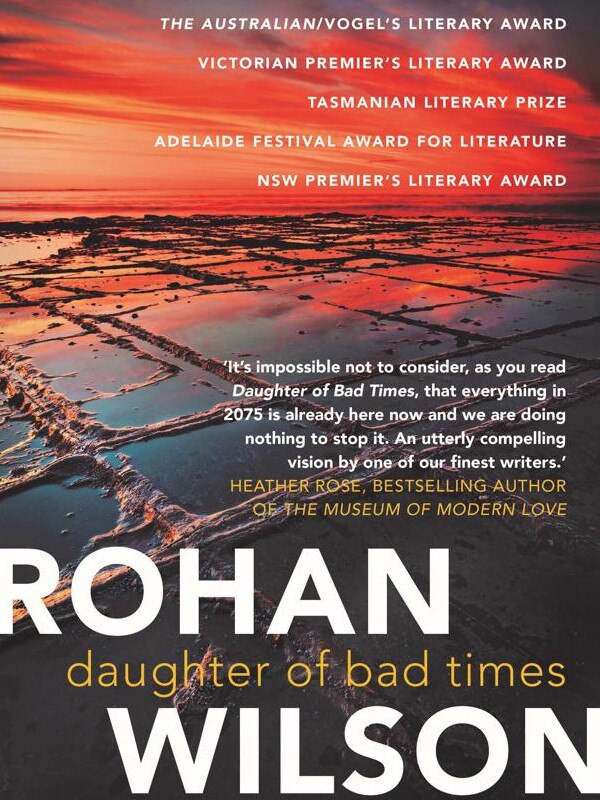

Acclaimed writer Rohan Wilson sets his latest searing novel 50 years into Tasmania’s future as refugees work like slaves near Port Arthur.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ROHAN Wilson looks sharp and boyish in his trademark narrow tie and mustard leather jacket when we meet at a lounge bar on Hobart’s waterfront. His grey-flecked hair is a bit of a giveaway, but it’s still a surprise when the multi award-winning Tasmanian author says he is 42 years old. That makes it about seven years since Wilson rushed aboard the icebreaking vessel known as The Australian/Vogel Literary Prize just a snowflake before the cut-off age of 35. Winning the award for first-time authors for his debut novel, The Roving Party, catapulted the unknown Launceston literarian to a dizzying height overnight (and he was already tall!), but Wilson is by no means an accidental author. He’s been planning this trajectory for most of his four decades.

He followed through with a second novel, To Name Those Lost, in 2014, along with more awards. Now Wilson has just released his third book, Daughter of Bad Times. Each of his novels is set in a different era, but Tasmania looms large in all three.

Having moved from the colonial frontier of the early 19th century to a riotous moment in the 1870s, Wilson thought a lot about what he’d do next. He decided to take a 200-year leap forward from his second book, setting Daughter of Bad Time s 50 years into the future. Time span notwithstanding, he says Daughter of Bad Times is the next instalment in the same overarching undertaking.

“The bigger project is talking about Australia, who we are nationally and in Tasmania, what our history is and how it shapes where we’re going,” he says. “And this time, a big thing for me was I wanted to write characters who had beliefs and ideas similar to my own. I was a little bored with the rough and tumble kind of guys.”

His freshly minted protagonist is nothing of the kind. Yamaan is a broken-hearted climate refugee from the Maldives living in Tasmania. The world’s flattest country has been devastated by a tsunami that Yamaan survived. Tricked into resettling in Australia on a “migrating with dignity” program, Yamaan finds himself working as a virtual slave in a detention centre operating as a factory on the Tasman Peninsula.

The labour of the indentured men is purportedly to pay off their migration debt. The centre’s proximity to the former convict penitentiary at Port Arthur is intentional, of course, says Wilson, though he expects only Australian readers will twig to the allusion. The novel opens with Yamaan standing at his post:

When Hassan asks if I could live in a coconut palm, what he’s really asking is whether we are the loneliest men in history. I look at him in workstation twenty-eight, fumbling with the pink shell of a TabaPet, and I know what he wants to hear and even how to say it; still, my heart isn’t up to the job …

For months, the young men have distracted themselves with hopeful imaginings as they work side-by-side on the assembly line. But today Yamaan won’t say how long he thinks a boy — specifically Hasaan’s tsunami-lost son — might survive if he were living in a tree.

“Well, I do,” Hassan says. “You could live for months. You could drink the rain. If you had a machete, you could cut the coconuts. Months. Easily”… Van Hooj patrols past with his baton drawn and we put our heads down. Work, work, work, and don’t talk — that’s the rule.

Alessandra Braden is a wealthy US businesswoman who runs Casey-Yasuda, a corporation that made its money managing jails before branching into immigration detention centres that double as manufacturing plants. Part of the company’s remit is the Eaglehawk Migrant Training Centre in southern Tasmania, in which thousands of environmental refugees from the Maldives and elsewhere are imprisoned.

Ever the opportunist, Alessandra was keeping an eye on the Maldives well before the tsunami, buying a holiday home there to mix business with tropical island pleasure. Yamaan works as a domestic in her household and that’s how he meets her difficult daughter Rin, who falls in love with him.

After the tsunami, Rin is desperate to find Yamaan, and when she does she must find a way to free him. When she does see him briefly at Eaglehawk, he is initially aloof.

“I’ve learnt that to love someone is to be shown the facts of your own predicament,” he muses. “That you’re nothing and no one, just a fool with a swollen heart. So I follow the old rule of my father’s: be as hard as bone or beasts will chew you.”

Dejected Yamaan is a calm and thoughtful narrator. He alternates storytelling chapters with Rin, who is much spikier and quite unpredictable. With the novel’s two points of view and a complex plot structure with three timelines to wrangle, it took Wilson a year just to plan it.

“Once I’d figured all that out, I had a book that I wanted to write and that I could bear to live with for three or four years while I worked on it every day,” he says. “That’s usually my challenge — finding what isn’t going to bore me to tears.”

He says setting the novel in the 2070s made sense. “We know that sea level rise is coming, but it’s probably not coming until the end of the century, so I needed to have a plausible and realistic timeline for that.

“When you think about the future [in general], you’re forced to think about climate change, so it felt dishonest to write about the future without talking about climate change. And when I started to look at climate change, it felt dishonest not to look at the countries most affected.

“I’m living in Brisbane in an apartment on the fifth floor, but for other people around the world, it’s an existential threat that their country is going to be destroyed. For people in the Maldives, climate change is like an apocalypse just over the horizon.”

He soon realised he needed to write a Maldivian character, his heart “sinking a little bit” because of all the extra research that meant. He managed a quick visit to the Indian Ocean nation. The Republic of Maldives is made up of 26 atolls and is mostly less than 1m above sea level. By mid-level estimate projections, more than 70 per cent of the country will be submerged by 2100.

Wilson spent just over a week rushing around the mostly Muslim nation, absorbing as much as he could. “I still have the habits I built up four or five years ago for my research, like reading the [Maldivian] newspapers every day,” he says. “I cheer their victories and I get angry when the politicians do these corrupt things that they tend to do.”

He is thinking about sending a copy of Daughter of Bad Times to former president Mohamed Nasheed, whom he believes to be a keen reader. “He’s a really lovely guy. He’s the one who brought the Maldives out from under authoritarian rule. I’ve often thought about sending it to him, but I’ve never had the courage, because if he didn’t enjoy it, it would break my heart.”

The corrupt corporate world Wilson describes in the novel may not be quite as catastrophic as the effects of global warming, but on this front he paints a chilling picture, too. And, alarmingly, it does not feel futuristic. Wilson says it wasn’t a stretch at all to create his fictional migrant detention centre.

“There’s almost nothing in the book that’s imaginary,” he says. “It all already exists in certain parts of the world, perhaps not with quite the efficiency that Casey-Yasuda manages. If you’re detained in the US as an illegal migrant, you’ll be detained in a facility that’s run by a for-profit corporation, and you’ll most likely be put to work for about $1 a day. That happens right now.

“We’re not quite there in Australia yet. The US is always a lot more capitalist than we are and a lot more gung-ho about exploiting people, but we’re nevertheless following on their path.”

He remembers driving past the former Pontville Detention Centre, an old army camp near Hobart that was refitted and briefly used early this decade to house asylum seekers while their applications were being processed.

“To see these refugees arrive and be rolled into these facilities made me start thinking ‘what comes next?’. Given the current economic climate, it doesn’t seem at all like a stretch to think that those refugees could be put to work by a government to help pay for the cost [and that] a lot of people in the community would [support that]. It’s not entirely implausible.”

In primary school, Wilson spent a lot of time stapling pieces of paper together to make books. “My teachers were constantly dragging me away from the scrap paper and trying to tell me to do other things,” he says. “And 10 minutes later, I would go straight back over.

“I never had doubts about what my career was going to be. I always knew. I just needed to be able to support myself doing whatever work I could while I wrote in my free time. Eventually I would get somewhere.”

Wilson attended Brooks High School in Launceston’s Rocherlea. He says it was “a pretty rough public school in a pretty rough area”.

“But, you know, you get out of it what you put into it, really,” he says. “I loved English there and my teachers always gave me interesting books to read and were always telling me I was good at it, and I should stick with it. I had that validation all the way through.”

A Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Tasmania followed, majoring in philosophy and history. In his late 20s he moved to Japan for five years to teach English as a second language. His plan was to make enough money to further his studies before launching as a writer.

In Japan, he fell in love, and realised just how much he was riled by authority. “I really, really hate being told what to do,” he says. “When I went to work for the corporation in Japan, they picked me up from the airport, they took me to my company housing, my wages were garnished — they would take the rent money out. They gave me a phone and they set up my phone contract. They did all this stuff. And they owned me.

“They could fire me at any time for any reason. If I was caught in a relationship with a student, I would be fired and sent home. If I was ever late, I would be fired and sent home.”

It turned out to be handy research for the new novel, but at the time he says it didn’t stop him flouting authority. Not after he met his wife-to-be, anyway, on the campus. “She was a student, yes, but she was also a staff member,” he laughs. “So we found a little loophole.”

Wilson and Machiko have a son Alan, who is 14. He says his wife is his greatest supporter. “I had kept telling her, ‘I’ve got to go back to Australia, I’ve got a book to write, I’ve got to get my degree’,” he says. “And she, to her never-ending credit, trusted me, believed that I could do it.”

After their return, the family lived on a low budget in Launceston and he commuted monthly to Melbourne for face-to-face time with his PhD supervisor.

He didn’t even promise her a bestseller in The Roving Party. He thought there was little chance of that with his brutal reimagining of Tasmania’s colonial frontier. “I knew that no publishers were going to be interested in it. I kept on because I thought it was important,” he says. “I thought it felt like a book that mattered.”

He was wrong about the first bit. Winning the Vogel, which brought automatic publication with Allen & Unwin as well as cash, was his dream come true. “It was so enormous that it was dangerous to let myself think what it would be like to win,” he says. “I had never published a single thing in my life, not even a short story.”

He knew the book could get him into trouble, though, having just written his PhD on the contentious place of historical fiction in relation to non-fiction history writing.

“Fiction readers know it can be read metaphorically or allegorically, that we are not trying to talk about truth in the same way historians talk about truth,” he says. “Nevertheless, we get measured against works of history. The history cops step in shaking their finger.”

As he wrote The Roving Party, he remembered the caning Kate Grenville received from some historians for her realist 2005 historical novel, The Secret River. Believing his novel to be more incendiary, he braced himself rather than backing off, doubling down on his research and his reimagining of the era.

“I was talking directly about the genocide,” he says. “John Batman is still considered a [settler] hero in Tasmania — we have bridges named after him in the North — but he was a more or less a bounty hunter. He was being paid by the government to conduct campaigns against Aborigines. Writing about him was always a little risky and dangerous.”

As it transpired, the history cops rested easy that time. And the literary world went nuts, hailing a major new talent in Wilson. Second novels are notoriously difficult to pull off after celebrated debuts, but Wilson did it. “A ferocious and brilliant sequel … there is a purity of vision in To Name Those Lost,” wrote a reviewer in the Australian Book Review.

Having immersed himself in the 1820s and ’30s for The Roving Party, Wilson shifted 50 years forward for book two, setting To Name Those Lost in 1870s Launceston, when riots broke out after a railway company building a line in the North went broke and the government bailed it out, putting a levy on all the households along the railway line to fund it.

“People were forced to pay to cover the losses of the shareholders in the 1870s,” he says. “I was writing this during the global financial crisis in 2008 and the same thing was happening. And in Tasmania it was around the same time that [timber company] Gunns was collapsing after prolonged public demonstrations. I saw a lot of parallels in all of that, and used those base conditions to tell a tale of Launceston in full-blown rebellion and revolution.”

Wilson, Machiko and Alan moved to Brisbane in 2015, just after publication of To Name Those Lost, for him to start a job lecturing in creative writing at the Queensland University of Technology.

“My long-term goal was always to get into a university, because I knew that as a writer it’s the best place to be,” he says. “I pinch myself every day. There are so many great writers out there and there are so few of these kinds of jobs.”

He says the institution takes fiction as an enterprise seriously, and builds writing time into its writers’ day jobs. “They consider it to be of high value, so they put resources behind us and really give us a push. They are really keen on people taking on social issues and taking on political issues in their work and engaging as a community.”

He embraces the lecturing part of the job, too. “Just being in a classroom and teaching is learning for me,” he says. His mantra to students is to believe that what they do matters.

“I’m always trying to remind them that writing is important, writing is a way to speak back to power, and writing is a way to change the world to become what you want it to be.”

As a tool of resistance with the power to influence many, the pen is famously mightier than the sword. But it is love that rules, says Wilson, and at its heart he sees Daughter of Bad Times as a love story.

“What I’m trying to say is that love is the only force that can’t be controlled,” he says. “It doesn’t matter what kind of systems or programs governments put in place. Love is anarchic. Love will upset power structures. And love is the one thing that will drive people into open rebellion.”

Daughter of Bad Times, Allen & Unwin, $29.99, is out now.