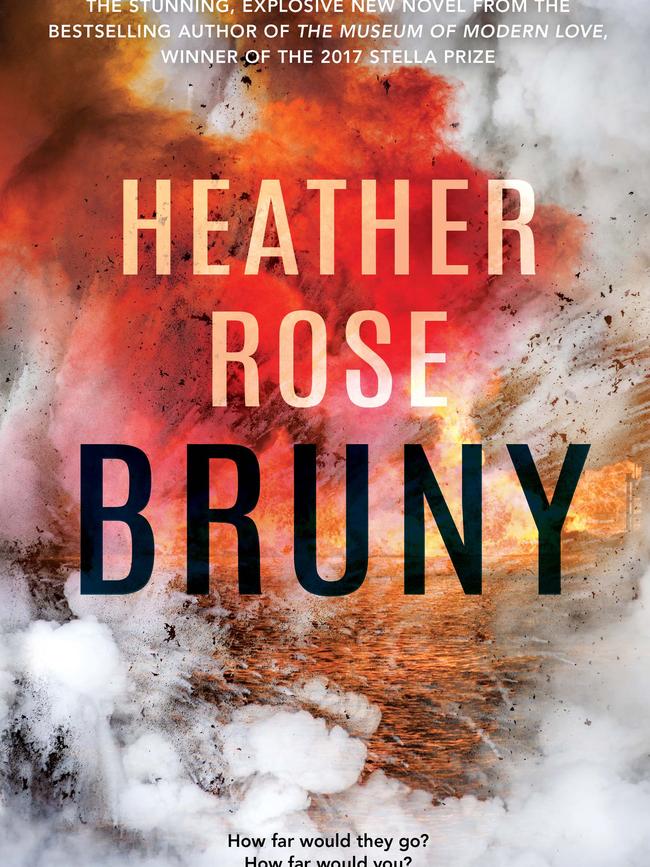

TasWeekend: Author Heather Rose examines political interference in her new novel Bruny

An explosive new novel opens a can of Tasmanian worms, wriggling in a web of bluff and subterfuge against a backdrop of local touchstones and accusations of foreign meddling. READ THE EXCLUSIVE EXTRACT

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HEATHER Rose can hardly believe the timing — and when the Tasmanian author’s eighth novel, Bruny, hits bookstores nationally on Tuesday, it is bound to rivet readers with its relevance.

You couldn’t have planned a better drop: part thriller, part political satire and part love story, the explosive novel is also a deep dive into Chinese political influence and ownership of key property assets in Australia.

Given the long lead time of novels in production, what are the chances of Bruny landing on the tail of three Tasmanian politicians speaking out in Federal Parliament about the Chinese Communist Party’s alleged activities in Tasmania, happening here as elsewhere via soft agents, complex property deals and, it would appear to some, government invitation?

By the time Independent Member for Clark Andrew Wilkie and senators Peter Whish-Wilson and Jacqui Lambie flagged concerns in Canberra, Rose had already issued invitations to next week’s Hobart launch event.

Early readers keep telling Rose she is brave, the author says in a late afternoon fireside interview at her Kingston Beach home 20 minutes’ drive south of Hobart. Her cat is asleep on a beanbag in the gracious old timber home, but Rose is full of beans.

Delightfully animated, she laughs often, usually at some perceived absurdity of life. So many people are telling her she is brave lately, she whoops, she is starting to get a bit worried. And it’s not just China she wades into, eyes wide open; her satirising of Tasmanian politics is deadly.

While Rose tackles some of the same issues as Professor Clive Hamilton in his gobsmacking 2018 expose, Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia, Rose has fictional characters to do her talking. Her outspoken, world-weary protagonist Astrid Coleman is a highly paid international conflict resolution adviser whose twin, the Premier of Tasmania, has called her home from New York to crisis manage the lead-up to the next state election. Astrid agrees, for her own reasons.

The state’s biggest infrastructure project, a $2 billion bridge to Bruny Island — a favourite weekend destination for generations of real-life Tasmanian shack and nature lovers — has just been bombed. And Premier John “JC” Coleman believes his chances of getting voted back in hinge on fixing and finishing the bridge before the March 2021 election, four months away.

When Astrid, recently divorced and the mother of two adult children, arrives in Hobart, she is met at the airport not by her overweight twin, but by their tiny older half-sister Maxine, who happens to be State Opposition leader.

If the reason for building the outrageously costly suspension bridge in the first place is opaque — it is federally funded and purportedly for tourist access, but few are buying that — the reason it has just been sabotaged are less clear.

As in all good thrillers, there are at least four or five individuals or groups who might have a vested interest in committing the act. Rose lets her characters sort it out among themselves.

Astrid reckons she’ll never get a straight answer from JC, even if he does know what’s going on. “He’s about as useful as an eyebrow on a dolphin in this situation. He doesn’t seem to grasp that he’s a pawn. But if JC is a pawn, who’s the queen on this chessboard? It sure isn’t America.”

Astrid thinks too much money is involved for the project to be true to its stated purpose of carrying half a million tourists to and from Bruny and the Tasmanian mainland annually. Why then?

It’s a leap from the bridge, but in a world of diminishing arable land, did the “vast bucolic wonder” of Tasmania make it a sitting duck?

“‘It’s the yellow peril,’ I could hear my mother saying,” muses Astrid. “She said it a lot when we were kids. This idea that the Chinese were going to invade at any moment. They were invading Vietnam at the time. But it wasn’t so much a fear of invasion here. More a sense that Tasmania — maybe even Australia — was being outwitted on the world stage.

“I had a bad feeling that, in five years’ time, people would be saying, ‘Why the hell didn’t we see that coming?’.”

In Rose’s political landscape, the wilful blindness of leaders who roll over at the first promise of short-term gain — or cash — is alarming, and Astrid has plenty to say on the subject. Rose lets her lead character have her head.

“If there’s one thing I’ve learnt after writing eight novels it is not to argue with my characters,” says the author. “They have their own way of doing things and the worst thing is to interfere … I didn’t think I was doing anything bold. I was just writing what Astrid said and what she thought. I would cringe at times and think ‘you can’t say that’, and then I’d say to myself, ‘oh well, it’s written now’.”

Rose thought she was writing something funny — and, indeed, it is great fun trying to guess which real-life politician may have inspired elements of which despicable character. But her agent set her straight after Rose delivered a solid first draft at the end of 2017.

“My agent said, ‘you’ve written a much more serious novel than you realise’, and it was kind of a revelation to me,” says Rose. “She sent it straight to Allen & Unwin [publishers] and three days later they made an offer on it.”

The world has only become crazier since then, says Rose. “All the ideas that went into this were swirling around three or four years ago. And now the [timing] is just bizarre. People who have read it keep sending me things from the press, saying ‘how did you know?’.

“I’ve been told it’s brave and bold, clever and brave, brave and shocking, brave and ‘what the hell have you done?’ This word brave keeps coming up and I am beginning to wonder whether brave means reckless, stupid, courageous or crazy brave. I don’t know. I was just the writer.”

Heather Rose, 55, is a slow-burn success. Her seventh novel was her breakthrough, propelling her into another league after it won multiple prestigious literary prizes, including the Stella Prize, and was published internationally.

The prize money and literary grant Rose picked up for 2016’s The Museum of Modern Love, inspired by performance artist Marina Abramovic, enabled her to write full-time for the first time. For many years, she ran a boutique advertising agency with her now ex-husband.

“It’s the strangest way to live, but being able to write full-time is also the most joyful and fulfilling experience for me,” says Rose. “I have always written at night and in any spare minute of the day. Suddenly, because of the Australia Council grant and then the prizes, I was able to write every day.

“I had a really regular schedule of being at my desk at 9am each day after seeing my daughter off to school, and working until 3pm when she came home. I often returned for an evening shift as well and wrote through many weekends.

“I was single-parenting and my daughter was in Years 10, 11 and 12 while I wrote the book, so it was still very busy, but I was able to return to my characters day after day after day. While the subject material often felt deadly serious, and I was immersed in global current affairs and myriad research, the momentum was a delight. I’ve waited all my life to be able to give myself to novel-writing day after day.”

There is no certainty she will be able to continue to write full-time, though.

“That’s so for almost all Australian writers, no matter how seemingly successful we appear,” she says. “We have a very small market of readers here, and unless you become an established international writer, there’s always a gruelling unpredictability of income.

“If a writer receives any royalties from their work (and there have been many, many years for me over seven novels where that was a zero sum game — once I received a cheque for 57c), those payments come twice a year, and you never know how much they will be.

“So it’s impossible to plan. All we can do is keep writing and hope to generate a new advance for a work that’s enough to cover the mortgage and the bills into that unpredictable future.

“That’s why grants and prizes are so important. Yet they are also taxed. If you win money at a casino or in a lottery it’s not taxed, and yet despite the incredible odds of winning a literary prize, it’s taxed.

“The same for grants — even though they’re given by the Government, they are then taxed by the Government. It makes no sense.”

For now, Rose is counting her lucky stars, having just heard she will receive another Australia Council grant. “That was my 11th application over 25 years and my second success,” she says. It will go towards funding the research and writing of her ninth book, which is historical fiction.

Rose’s family has lived around Kingston Beach for four generations. Her inspiration for Bruny came to her on a walk along the sweep of beach in front of her home.

“If you walk to the dogs’ beach end, you look straight down the river and you see North Bruny and you see Tinderbox [on the near side],” she says. “Maybe it was a trick of the light, maybe my imagination, but I saw an enormous bridge and I thought, ‘That’s a funny idea — why would there be a bridge to Bruny Island? What’s going on?’.”

Within minutes, the character of Astrid appeared in her mind’s eye. She was arriving home at Hobart Airport to be collected by Maxine.

“You can tell Astrid’s a world traveller by the way she’s dressed, and this diminutive woman picking her up, who seems to be known by everyone, is clearly her sibling. They drive home to Sandy Bay for a family lunch.”

Rose realised with a jolt whom she had just conjured. “I thought, ‘I know you! You’re the Colemans’,” she says. “I had written a short story about them at a writing course in Melbourne when I was 21. I don’t remember what the topic was at that Christmas-table family gathering, but I do remember it was one of those conversations that is all very nice on the top, but underneath there’s subterfuge, tension, unresolved stuff.

“I just didn’t have the maturity to write them then. I couldn’t make it work, but they’ve stayed with me all these years.”

The Colemans are worth the wait. Rose’s handling of tricky family dynamics is masterful and often funny. Astrid’s difficult relationship with her mother is excruciatingly well portrayed.

Rose says one of her most enjoyable writing challenges with Bruny was finding words for Angus, Astrid’s dementia-afflicted father, who speaks only in Shakespearean quotes. Though Rose knew many of the plays, having trained as an actor, her memory was rusty, so she returned to the tragedies and comedies to pluck out poetically pithy remarks.

She says she was charged with energy writing the book. “I felt as if a grandmother were beating me on the back with a bamboo stick saying, ‘write harder, write faster’.

“It was the most intense writing experience. It would wake me up at night. I have never felt so compelled to write anything in my life. And a novel is a long thing to be compelled by.”

She also immersed herself in current affairs. “I did an enormous amount of research,” she says. “Because it’s slightly to the side and slightly ahead of current times, I had to imagine what would happen in a slightly altered world.”

Bruny Island is one of Rose’s heartlands. “I’m a sixth-generation Tasmanian and Bruny has always been part of our lives. Bruny has an isolation that is so precious. It was just marvellous when there was no mobile reception over there. It used to drop out about three minutes after you got on the ferry.”

As a child, her family made day trips to the island for picnics and play, catching the car ferry from Kettering, which still provides the only access other than by private boat. As a teenager, she swam and surfed at Cloudy Bay on South Bruny.

Later, after returning to Hobart with her young family after years living in Melbourne, she often took her brood to Bruny for the weekend, staying at favourite rentals.

It was her publisher, though, who suggested naming the book after the island, which is in turn named after French explorer Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux. Rose says she was going to give it the satirical title of Hobart: City of Love.

“We have to love each other, because we live in such close proximity,” she says, smiling. “I think it’s the most amazing thing about our community here that people hold very different views and still respect each other.”

So she’s not expecting Tasmanian Premier Will Hodgman to stop talking to her when Bruny comes out? No, she laughs.

“I told Will a couple of years ago I was writing a political satire and that there was a premier in it, and he said ‘should I be worried?’.

“Apparently I paused, looked at him and said ‘a little bit’.” She giggles, adding that the political dynasty she portrays is not based on the Hodgmans.

Despite the ominous warnings embedded in the story, Rose is also expecting Tasmanians to have fun with the book. While she disses the political masters and some aspects of the culture that spawned them, Bruny is unmistakably also a love letter to Tasmania.

“I wrote it for Tasmanians for many reasons,” she says. “First of all, I wrote it for my love of Tasmania as a community and a landscape, as a place at the end of the world that is so rare in the modern world.

“It was a privilege for me to immerse myself in my love of the place and the community and to reflect the values we hold — despite different political perspectives, a lot of us have the same set of values about community and connection and about generosity and kindness.”

She wants her book to inspire reflections and communication about those values and the best way to safeguard the Tasmanian way. “I think we need to have better conversations to make sure these values are not at risk,” she says.

“The things challenging us, whether foreign ownership or polluting the river — or the issues of the past such as hydroelectricity schemes, deforestation and pulp mills — require or have required of us really considered thought.

“I wanted to write about what it feels like to live here — and therefore what makes it worth protecting from all sorts of things challenging us on a global scale. This is a magnifying glass on the culture and landscape of Tasmania and what we hold dear, but it tells a global story.”

It would be an unfortunate irony, I suggest, if the thing that really puts Bruny the island on the international map is Bruny the book.

“About half a dozen early readers of the book in Sydney have already come down here since reading it because they were fascinated and they have said, ‘wouldn’t it be terrible if your book caused there to be a bridge to Bruny,” she says with a laugh. “If I’d had enough money, I’d have bought a bit of land on Bruny before the book came out.

“Seriously, though, I would be devastated [if the book had that impact]. That’s the truth. But let me say that’s the challenge. We are going to get more tourists here. We are an uncrowded, relatively pristine environment in an overcrowded, far from pristine world. People yearn for this connection we have with nature and take for granted every day.”

It is Bruny’s male lead, Dan, who makes the observation that people give up a lot to live in Tasmania. There’s electricity flickering between the pair as Astrid asks him why Tasmanians protest so well. “Why are they so averse to change?”

“Well, we already gave up a lot just to be here … Most of us could have done something else. Gone interstate or overseas. Could have lived bigger lives. Had fancy homes and a fat bank account.

“When you settle for Tassie, you’ve settled for less in some ways; less of what matters out there, more of what matters here. If someone wants to change that, take what you love about it away, you get pretty shirty. So we fight for what’s ours, what’s left. Because it’s what we have. It’s all we have.”

Flowing from another set of life choices, Rose thinks she would probably be running an advertising agency in Melbourne or nailing it in New York. She has no regrets. Give up her Tasmanian life? “Not for anything,” she says. “It’s paradise, and it is possible to live a very well-rounded life here in a way that is increasingly difficult in big cities,” she says. “And I think it’s worth a powerful, open community conversation — about what we want Tasmania to look like in 25, 50 and 100 years.”

Getting back to that word “brave” and to what she has written, Rose says her biggest worry on the eve of publication is that she will be accused — falsely, she is adamant — of racism.

“That is my biggest concern,” she says, “but I don’t think it’s racist to question the role of ideology in politics. I would challenge anyone to find a single paragraph that would be considered racist in the whole book.

“I think the political ideology that we see rising in the world at the moment is very concerning to a lot of people, and there’s no way Tasmania will not be impacted by that into the future.

“I think that’s where art is at service to society. Creativity can help us come at issues from a different perspective. That has been the role of literature and writers for centuries: to stimulate debate, to create conversations, to reflect the world in a way that helps people understand it with different insights. If I am doing that, I am doing my job.”

Our conversation circles back to Shakespeare and famous lines uttered by Astrid’s old dad Angus, including “I never did repent for doing good, nor shall not now”, spoken by Portia in The Merchant of Venice. “I should use it as my refrain for the book, by the sound of it,” says Rose wryly.

Bruny, Allen & Unwin, $32.99 comes out on Tuesday.