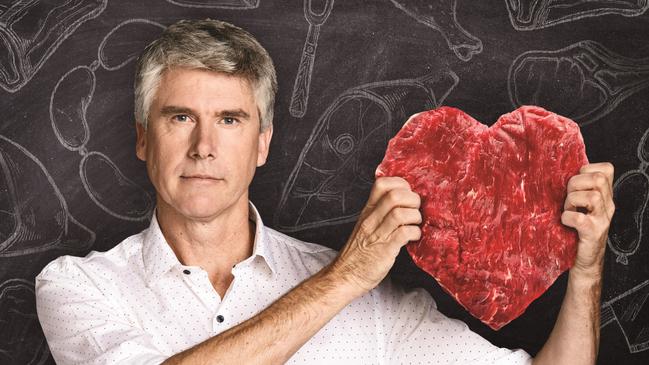

TasWeekend: Matthew Evans, the carnivore with a heart

Who is entitled to call themselves an animal lover, asks Gourmet Farmer Matthew Evans, as he delves into the ethics of meat-eating in a culture of secrecy and extreme views.

Food and Wine

Don't miss out on the headlines from Food and Wine. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MATTHEW Evans was rubbish at being vegetarian. He tried to cut out meat in his university days in Canberra. “I’d go to someone’s house and they’d say ‘oh there’s only a bit of meat in it’ and so I just ate whatever they gave me,” says the ex city-slicker chef and restaurant reviewer, who is best known today as the Gourmet Farmer of SBS TV fame.

That seemingly worthy vego phase didn’t last long, but Evans remained ethically conflicted about eating meat for decades. When he started raising animals to eat, he knew he had to do something about it. A big part of his problem was that he did not know who or what to believe. In his new book, On Eating Meat, Evans shares the findings of a years’ long truth-seeking mission that has seen him rejected time and again from entering factory farms even as he gets up the nose of animal libbers. He reserves particular annoyance for self-righteous vegans.

The debate has been hijacked by extremes, he says. Intensive farms operate in intense secrecy that is occasionally breached by hard-core activists trying to save animals living and dying in abhorrent conditions.

“I’m angry at the industry and I’m angry at animal activists, because they’ve spent decades taking videos and trying to expose some of the atrocities, but all they have done is polarise the debate, and we have worse animal welfare outcomes today than we had 50 years ago,” Evans says.

“What happens is we hide farming practices when we should explain. We treat consumers with disrespect, not trusting them with the information on how food is really produced, be it plant or animal.

“We’ve purged our city lives of the dirty business of how things are grown and farmed, and what makes it wrong is that we then marginalise, and sometimes demonise, those who have to do those things for us.”

In that environment, is it any wonder sensible farmers and meat-eaters retreat from the conversation, he asks.

Troubled by the chasm, Evans set out to learn more after moving from Sydney to Tasmania more than a decade ago to take up small-scale farming. “I wanted to know whether what I do and what other people do is causing general harm,” he says. “Is meat as bad as the headlines say it is?

“When people stop traffic in the centre of Melbourne and say ‘Meat is Murder’ and the fact we raise animals to consume them is inherently evil, well, I am interested in those sort of ideas.”

As a farmer, he disputes these assertions, saying they are no more true than the fallacy that animals raised in intensive sheds can live normal lives and enjoy simple pleasures such as warming themselves in morning sunshine after a cold night.

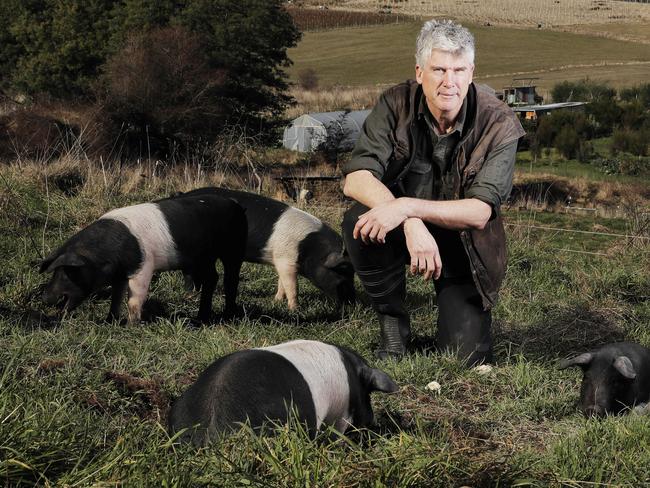

Evans and I are enjoying just that experience this morning over coffee and dutch-spiced biscuits at Fat Pig Farm in the Huon Valley. It’s a beautiful crisp clear day in a week of heavy frosts in Australia’s southernmost shire. His pigs’ water troughs froze over again last night, but thankfully the restaurant water pipes didn’t, having seized up in in below-zero temperatures two mornings ago.

The 28ha mixed farm spreads out along the floor of a pretty valley near Glaziers Bay. About two thirds of it is used for raising animals and food crops. Wildlife claims the hilly forested fringes, with wattles, eucalypts and a winter creek providing habitat for wallabies, bandicoots, bettongs, quolls, eagles, hawks and more. A winter creek flows.

This bountiful yet humble plot is where Evans and his teams work the land, run a restaurant, film a long-running TV series, plan food documentaries, write cookbooks and run workshops. It’s also where he retires at night in a cute timber cottage, thanking his lucky stars he has his stalwart partner Sadie Chrestman beside him every step of the way, and their 10-year-old son Hedley, who gives their labours another dimension of meaning.

Evans’s core position on meat is that there is a rightful place for it in the 21st century human diet. He’s researched and thought about it a lot — possibly more than most humans in history — and, to him, it just makes sense.

He spent years cogitating over the ethics as he roamed the paddocks in his gumboots and years researching the environmental impacts to come so definitely to this position.

Today he says he feels no personal guilt about growing and killing of animals for meat, though the slaughtering process is never enjoyable. His mood changes on home kill days, when he tenses up and braces himself for hours before the final act, which he sometimes delegates, sometimes shares and sometimes undertakes alone.

“If I was the beast to be slaughtered, my muscles would be dark, my meat tough,” he writes, imagining the coarsening effect of adrenaline rushing through his body. “There is nothing, I repeat nothing, nice about seeing a warm-blooded animal take its last breath. Anybody who thinks there is probably shouldn’t be anywhere near a kill.”

He has no qualms about eating meat from animals that have had a good life and whose footprint has been unexceptional.

“I think it’s a really beautiful thing to eat,” he says. “I think a lot of people really like the flavour and get pleasure from it, and It’s culturally part of the fabric of our society.”

When he started farming, Evans didn’t know much about how it all came together. Running a mixed-enterprise has taught him a lot about the synergic value of raising both animals and plants. He thinks meat animals, as well as those raised for dairy and eggs, have a place in most food-growing systems, including plant-dominated ones.

“There’s really good research from sub-Saharan Africa where they know they can produce more food per hectare using animals as part of the system than just plants alone,” he says. “There’s a whole bunch of bits of plants we can’t eat, but animals can, and then they magically turn those into meat.”

He points across to the farm’s grassy south-facing hill, a section of which has been excavated to create a carpark for the stream of guests visiting the farm’s long table lunches and occasional cooking classes. For some fans of the TV show and his cookbooks, Fat Pig Farm is little short of a pilgrimage on their trips to Tassie.

“See how steep and overshadowed it is? There’s nothing you can grow on that hill but grass,” he says.

“But the nice thing is that if you grow grass, you can grow food. We can’t digest grass, but a cow, sheep or goat can, and they turn grass into something we can not only eat, but is super high-quality protein and with a really high nutrient density.”

Meeting many other farmers through his business and media activities has given Evans broader insight into the ethics of eating meat and the ethics of food production and consumption generally. He has a lot of respect for farmers in general, but self-righteous vegans really get his goat sometimes.

“This idea that nothing dies or gets hurt if you are only eating vegetables, nuts, grains and seeds is such a lovely romantic notion, but it is false,” he says.

“Farmers everywhere are killing things all the time so you can eat. Whether you eat vegetables, whether you eat meat, whether you eat fruit, whether you eat grains, it doesn’t really matter — something has always been affected.

“Vegans are welcome to voice their opinion that raising and eating meat has consequences. Indeed, some of those consequences, from the personal to the animal to the environment, are worth some serious thinking about. It’s quite possible that eating less meat might mean less suffering. But don’t be fooled into thinking being vegan hurts no animal.”

He tells a story about visiting a 2700ha mixed farming enterprise in northern Tasmania that grew peas some years. Though the 75ha pea patch was fenced, the farmers also shot about 1500 animals a season to protect it.

“They had a licence to kill about 150 deer and they routinely kill 800-1000 possums and wallabies every year, along with a few ducks,” he says.

Every time we eat peas, he says, animals have died in our name. “Looking further afield, the number of animals that die to produce vegan food is astonishing,” he says.

Notwithstanding friendly backyard growers who avoid harming wildlife, Evans’ overarching question remains: Who is entitled to call themselves an animal lover?

Nature itself is cruel, he says, and every human activity has an effect on other living things.

“Vegans can make a choice not to knowingly consume animal products, but it does seem food production gets unfairly singled out for killing animals.”

Half a million native animals are killed on Tasmanian roads every year, he says, citing a figure endorced by the Royal Automobile Club of Tasmania.

“Should we get rid of our cars?”

What about last week’s cull of hundreds of wallabies on Maria Island on the East Coast?

“Nature at work is brutal, but it wasn’t a real drawcard for the island, watching survival of the fittest in real time. We can’t bear to see wildlife starve, so we close the island and shoot them when the public can’t see.

“I’d like more people to join a sensible discussion about animals, their use for food, and the impact on them from farming and other human activities.”

In his book, Evans calls for a “spirited, intelligent, respectful dialogue” that includes meat eaters, non-meat eaters and farmers. “Sadly, up until recently, with extremists on both sides dominating the debate, all we’ve seen are worse outcomes for intensively farmed animals,” he says.

“I don’t really think I want animal rights groups like PETA deciding these issues for the community — nor the owner of a feedlot who relies on the cheapest grain possible.”

Sections of the book are outright disturbing. A chapter on so-called minimal disease pigs or specific pathogen-free (SPF) pigs is particularly chilling, and goes way beyond the controversial farrowing crates that limit a sow’s movements to prevent her squashing any piglets.

This management system in Queensland involves slaughtering the sow, cutting the piglets from her uterus and moving them immediately away to avoid disease transfer from her body. The piglets are so immunologically comprised they have to be placed straight into a kind of humidicrib, says Evans.

“Can we really have invented a system like this?” He asks. “Is this the agricultural future we want?”

Evans roamed far and wide to research the book and the documentary he made before it, from shade-less cattle feedlots in searing Central Queensland heat to free-range chicken farms that are happy to show the media that part of their operation while hiding their ongoing mainstay business of cage farming.

Evans doesn’t hold back in attacking their shortcomings. It’s a sign of his open-mindedness, though, that he calls out his own limitations, too.

“On our farm, we fail the supermarket test, just like everybody else,” he writes. “I am particular about my pork, unlike many — but yet I have bought down jackets that may have been the product of live-plucking of ducks.

“And I’ll buy a work desk with no research into the environmental outcomes of its manufacture, or the conditions of the people who made it.”

Most of us are better in our heads than we are in reality, he says. But that should never stop us working to close that gap. “Minimising suffering is the responsibility of all who farm, and all who use what farmers produce.”

Global average meat consumption is about 34kg a year, but 2018 figures from industry body Meat and Livestock Australia show we eat four times more beef and veal than the global average, and six times more lamb than the rest of the world.

Averaging 111.4 kg of meat each, most Australians could easily and healthily pull back on their meat consumption, says Evans, leaving that bit extra in the wallet to buy meat less frequently but more selectively, bearing animal welfare concerns and environmental outcomes in mind.

The problem is not too big to face, he says, and consumer sentiment can drive the fix.

“It’s really powerful,” he says. “You see that in the increase of free-range eggs. That wasn’t legislated. That was a consumer-driven campaign.

“Sadly, the legislators changed the definition of free-range, but it’s still people with a conscience saying, ‘you know what, today I’ve got a little extra money in my pocket, and I would like to make a change to an animal’s life’.

“It happened with free-range eggs and it can happen with pigs. It can happen with meat and chickens — it can happen with everything.”

Acknowledging that just feeding their families well day-to-day is a financial struggle for some, Evans believes many more Australian are in the position to subtly adjust their choices. It all comes down to caring enough, he says.

“These are questions for people who have, I guess, the luxury not to have to worry about getting enough food or enough of the right food on the table.

“But I think it’s a stain on our culture if we choose to ignore the needs of the animals that are in our care.”

On Eating Meat: the truth about its production and the ethics of eating it, Murdoch Books, $32.99, comes out on Monday. A Hobart launch is on Thursday July 25 at Fullers Bookshop. Season five of Gourmet Farmer launches on SBS TV on Thursday August 1, at 8pm, with a focus on soil health at Fat Pig Farm.