Russia war could keep house prices high and interest rates low

The economy is rocked with uncertainty but signs are pointing towards Aussie house prices continuing to rise by record amounts.

Economy

Don't miss out on the headlines from Economy. Followed categories will be added to My News.

What happened in the pandemic was totally unexpected. Cast your mind back to March 2020 and the forecasts were full of doom and gloom for house prices.

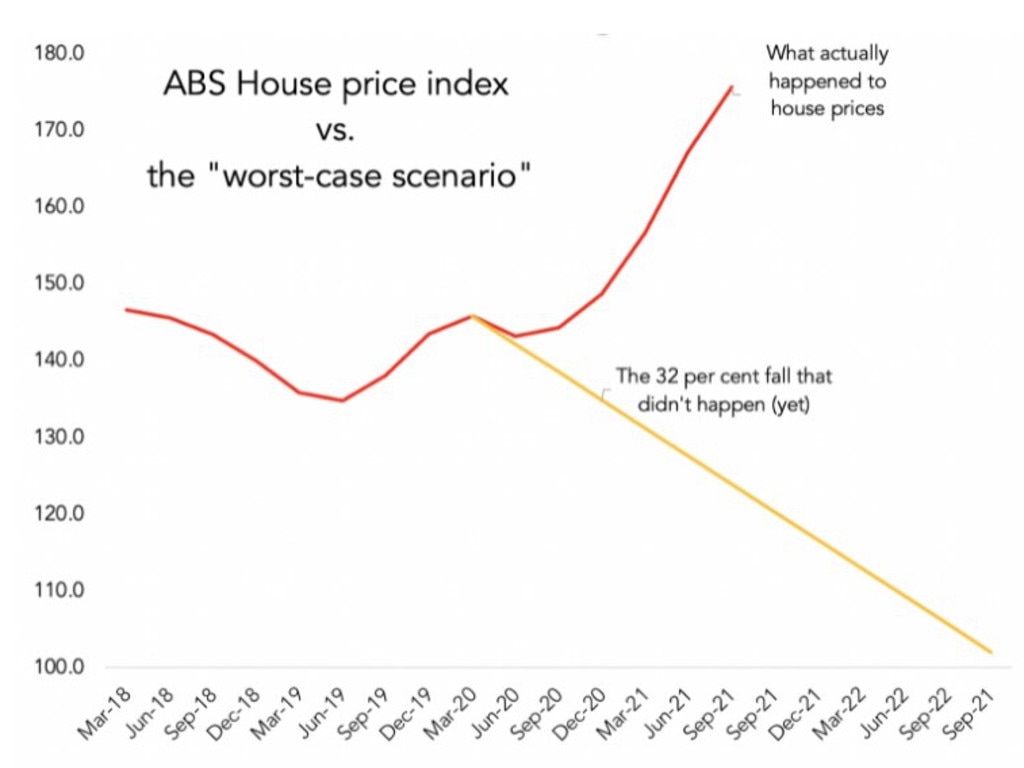

Commonwealth Bank had the boldest worst case scenario with a fall of 32 per cent forecast if things went badly. Their “central scenario” in May 2020 was a 10 per cent fall in the following six months.

The difference between what was forecast and what happened was phenomenal. One of the biggest misses I’ve ever seen.

After a brief and very small fall in the very earliest days of the pandemic, house prices began to stabilise, then lift, then roar upward at a record pace. They rose 21 per cent in the year from September 2020 to September 2021. It’s astonishing. And also horrific, if you think affordable housing is good.

So why did house prices rise so strongly?

A huge part of the reason is the government’s response to the pandemic. The government did a lot. Especially when it came to monetary policy.

You know what the RBA did – it cut official rates to record lows. We never went negative but we are tracking along with official interest rates at 0.1 per cent. which has been enough to squash some mortgage rates under 2 per cent.

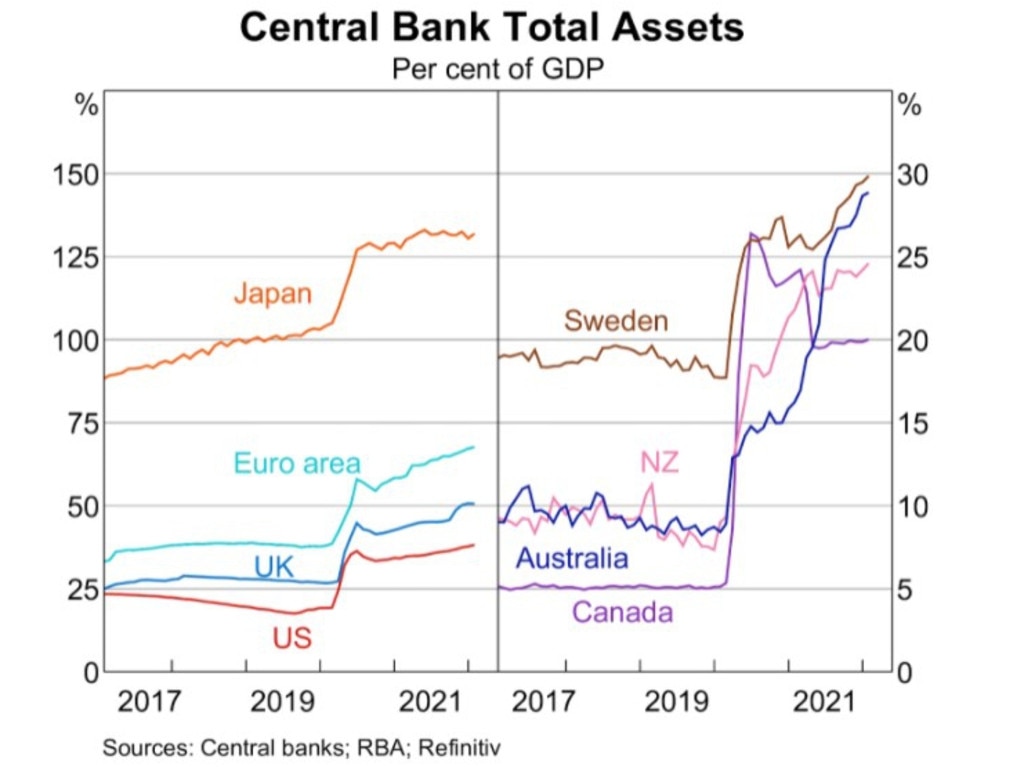

But that’s not all. Check out how many bonds the RBA bought. Hundreds of billions worth. The RBA is stuffed full of assets now, as the next graph shows (we are the dark blue line).

It bought those assets using cash that it made out of thin air. It took in financial assets (bits of paper, e.g. bonds) and sent out cash. Much of that cash is now out and about, circulating in our economy, making loans and propping up asset prices.

The low interest rates and furious bond-buying by the RBA are without question the major cause of Australia’s rocketing borrowing to buy houses. It certainly isn’t population growth doing the work.

Look at this next chart on borrowing. It has basically turned vertical. And then when it looked like it might finally fall it changed its mind and went up again.

So if we can have rising prices in a pandemic, can we have them in a war?

The fog of war

You’d expect a war to be bad for the economy. It’s bad for confidence. Things like this can spiral into complete global disaster. We could all perish under the mushroom cloud. OK, that’s been true for 70 years now but the chances just went up a bit.

The probability of nuclear holocaust remains thankfully small and has a small effect on our economy. The probability of widespread inflation, however, is very high.

Inflation – i.e. rising prices – is going to be the hot topic of the next six months. The crisis in Ukraine is making petrol more expensive – and food too. Especially food. Wheat futures just doubled as the next graph shows. Hope you’re ready to go keto.

Inflation and uncertainty make the economy weaker than it would otherwise be. Will that drive house prices down? They fell in January in Sydney. But that was before the war began.

Every action has a reaction

The answer we learned from the pandemic is not to just look at the disaster, but also the response to the disaster. And what we see is the RBA is responding by edging away from cutting interest rates.

“The war in Ukraine is a major new source of uncertainty,’ the RBA said on Tuesday as they once again chose to leave interest rates at low levels.

They insisted they will be “patient,” which you could interpret as meaning that they will leave interest rates low as long as humanly possible.

“The Board is prepared to be patient as it monitors how the various factors affecting inflation in Australia evolve,” the RBA said on Tuesday.

The RBA has promised that it won’t lift interest rates … “until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range.”

There are two words in there that give them wiggle room: “actual” and “sustainably”.

For example, “actual” does not mean actual, actually. They forecast actual consumer price inflation to be way higher than 3 per cent. But they won’t focus on that because it contains petrol prices and petrol prices are going to be pushed up by the war, and therefore could come down again.

But even underlying inflation, which excludes volatile, fast-moving prices, is expected to go over 3 per cent.

They forecast underlying inflation to hit 3.25 per cent … “before declining to around 2¾ per cent over 2023 as the supply-side problems are resolved and consumption patterns normalise,” the RBA says. “The CPI inflation rate will spike higher than this due to the higher petrol prices resulting from global developments.”

The upshot of all this is it seems the RBA will not hike rates even if CPI goes over 3 per cent, and even if underlying inflation goes over 3 per cent. Is that interpretation right? Market pricing of interest rate futures confirms it probably is right.

The market used to be pricing in more than two rate hikes by August. Now it is pricing in just one and a half. So expectations for rate hikes are down a lot since the war started.

Given the way low interest rates prop up housing prices it means the war could extend the housing boom. Tough thing to hear for those among us who are still saving a deposit, fighting against rising rents to reach 20 per cent of a number that gets larger and larger and larger.

Jason Murphy is an economist | @jasemurphy. He is the author of the book Incentivology.

Originally published as Russia war could keep house prices high and interest rates low