Rising inflation could end Australia’s housing boom

The booming Aussie property market is riding on one thing definitely not happening – but this week we got one step closer to the opposite.

ANALYSIS

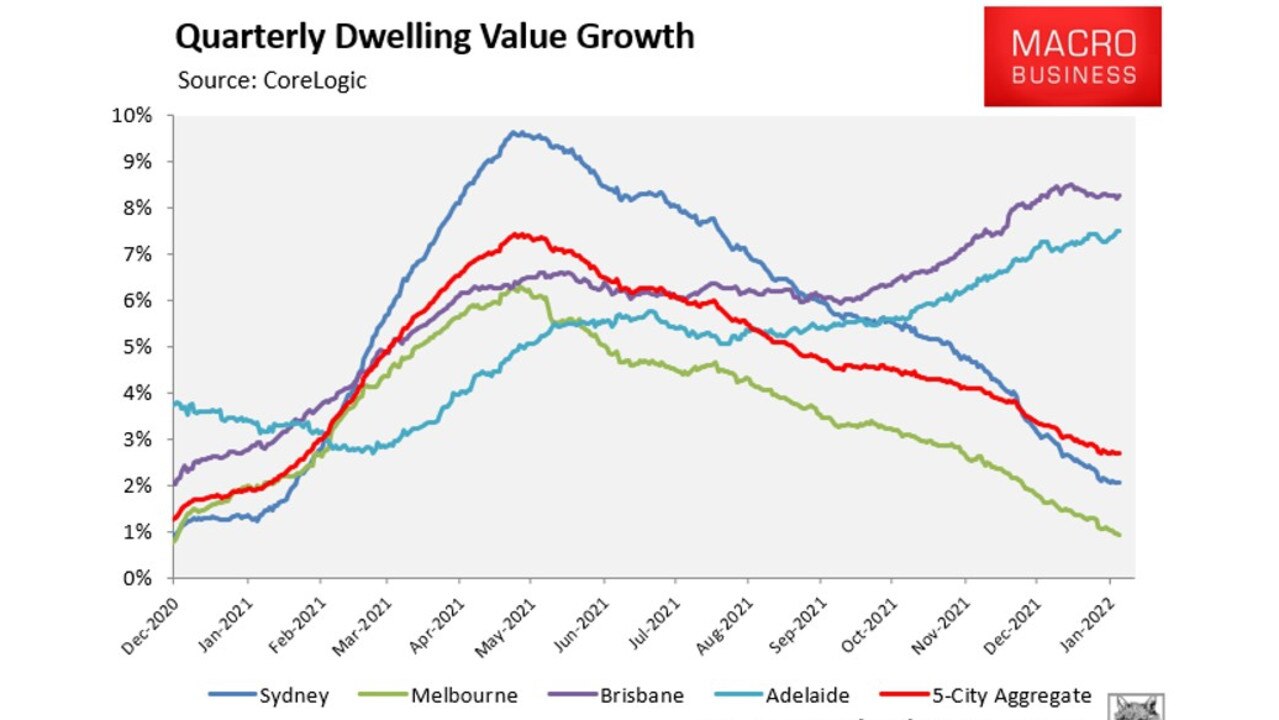

After rising a whopping 22 per cent in 2021 – the strongest annual growth since 1989 – Australia’s house price boom has begun to run out of steam.

Price growth across Australia’s two largest and most unaffordable housing markets – Sydney and Melbourne – slowed significantly over the second half of 2021 – a trend that has continued into January 2022.

This slowing momentum across our two largest cities has, in turn, pulled down national dwelling value growth, despite smaller markets like Brisbane and Adelaide still running strong.

Fixed mortgage rates on the rise

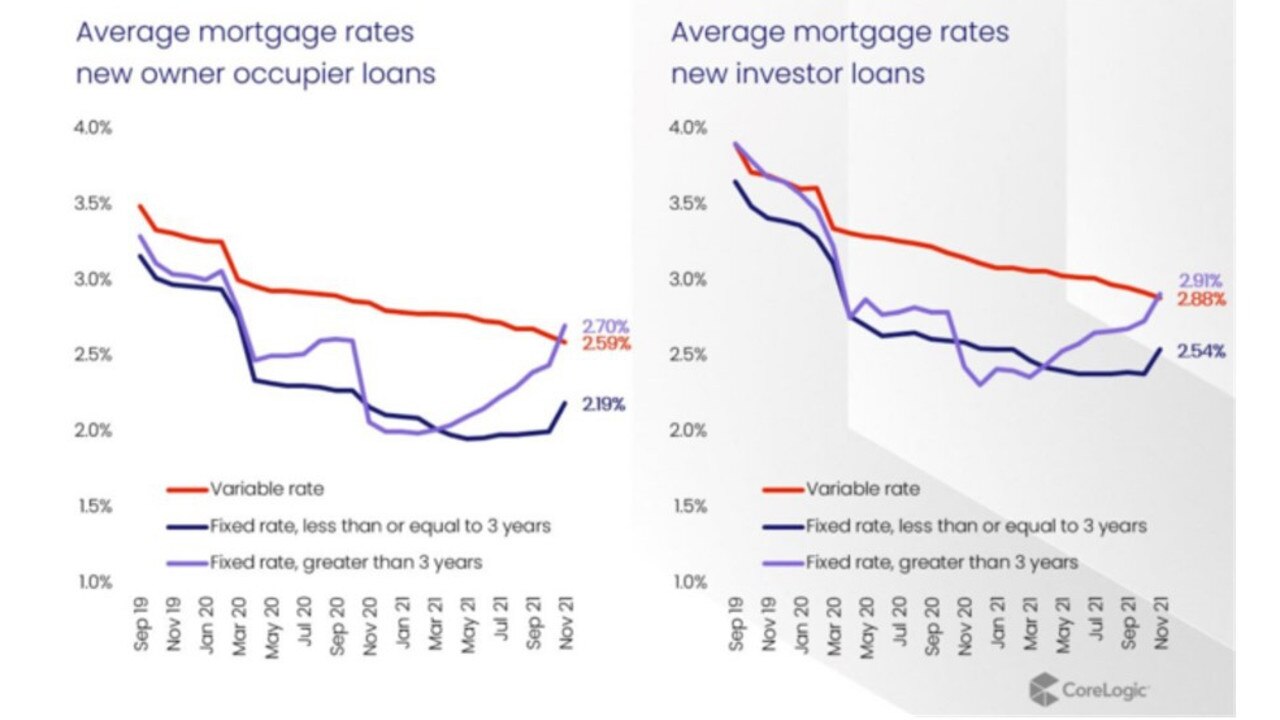

One of the key drivers behind this loss of house price momentum is rising mortgage rates.

Although the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has kept the official cash rate on hold at a rock bottom 0.1 per cent, in turn keeping variable mortgage rates at their current record low levels, fixed mortgage rates have crept higher in response to the RBA tapering its quantitative easing program.

A year ago, an owner-occupier homebuyer could obtain a fixed-rate mortgage with greater than three year’s duration below 2 per cent. Now average rates on these same mortgages have risen to 2.7 per cent, according to CoreLogic.

It is the same story for fixed rate investor mortgages of greater than three year’s duration, which have risen from an average low of around 2.4 per cent a year ago to 2.9 per cent currently.

Smaller increases have also occurred for shorter duration fixed rate mortgages across both owner-occupiers and investors.

Inflation to drive variable mortgage rates higher

The bigger story surrounds variable rates, which comprise the majority of Australian mortgages.

The RBA has consistently argued that inflationary pressures would only emerge gradually and modestly. Accordingly, the Bank issued guidance that it would not lift the cash rate until late 2023 once underlying inflation is sustainably within its target band of 2 per cent to 3 per cent.

The RBA’s guidance, in turn, suggested that variable mortgage rates would remain on hold for at least another 18 months.

This week’s consumer price index (CPI) inflation data for the December quarter obliterated the RBA’s expectations.

The RBA had forecast that underlying (core) inflation, which adjusts for the impact of irregular or temporary price changes in the CPI, would be 2¼ per cent/yr at Q4 21, thus implying a quarterly growth rate of around 0.6 per cent over the December quarter.

Instead, underlying inflation smashed expectations, coming in hot at 1.0 per cent over the quarter and 2.7 per cent year-on-year.

Markets and analysts believe this higher than expected inflation will force the RBA to raise the cash rate later this year, in turn lifting variable mortgage rates from their current record low level.

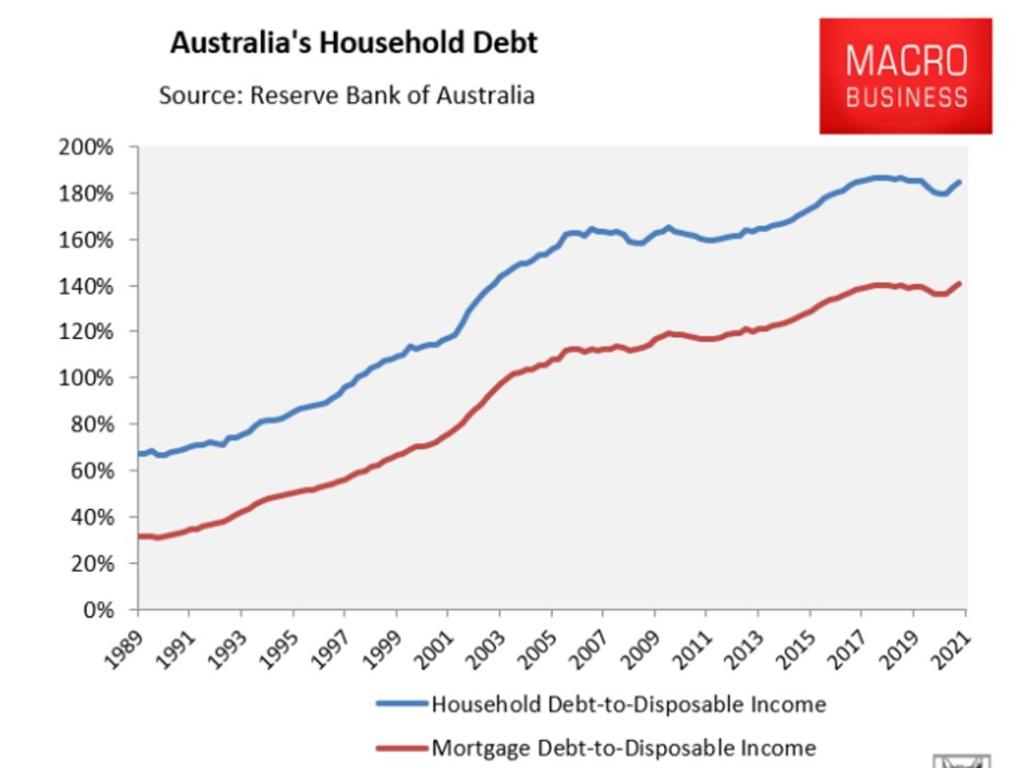

If this happens, it will place strong downward pressure on Australian property prices given our household’s gigantic stock of debt (ranked second highest in the world).

The cratering of mortgage rates to record lows over the pandemic was the key driver of Australia’s current housing boom. Therefore, it stands to reason that raising interest rates would have the opposite effect in delivering a house price correction.

My view is that the RBA will wait for next month’s Q4 wage growth data before changing its interest rate guidance, since this will indicate the degree by which inflation is being domestically generated rather than imported.

Interest rates are a demand management tool. As such, there isn’t much sense in raising rates to counter imported (cost-push) inflation.

Australia’s wage growth was only 2.2 per cent in the year to September 2021, and the RBA has indicated that wage growth needs to move above 3 per cent before it will trigger sustainable inflationary pressures.

More Coverage

Given the tightness in the Australian labour market, which has seen both unemployment (4.2 per cent) and underemployment (6.6 per cent) fall to their lowest levels since 2008, there is a good chance that wage growth picked-up in the December quarter.

If wage growth solidly beats expectations in Q4, then the RBA will very likely bring forward its guidance for interest rate rises, in turn sounding the death knell for the Great Pandemic Property Boom.

Leith van Onselen is Chief Economist at the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.