Joanne Harris v JK Rowling – the literary spat of the summer

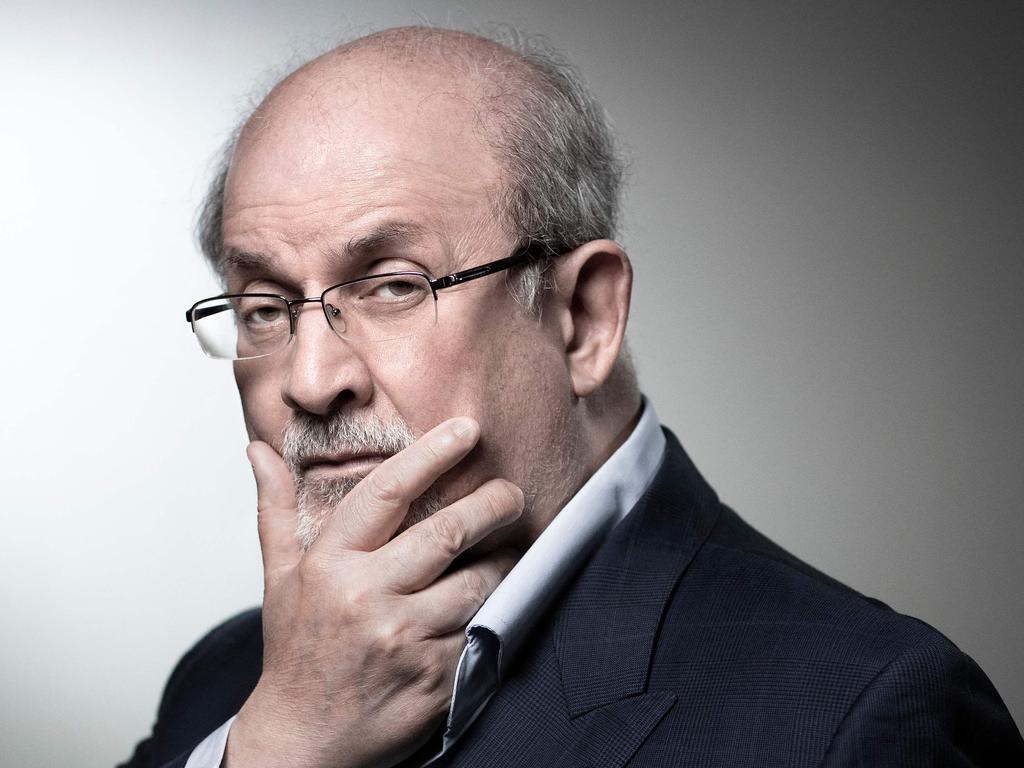

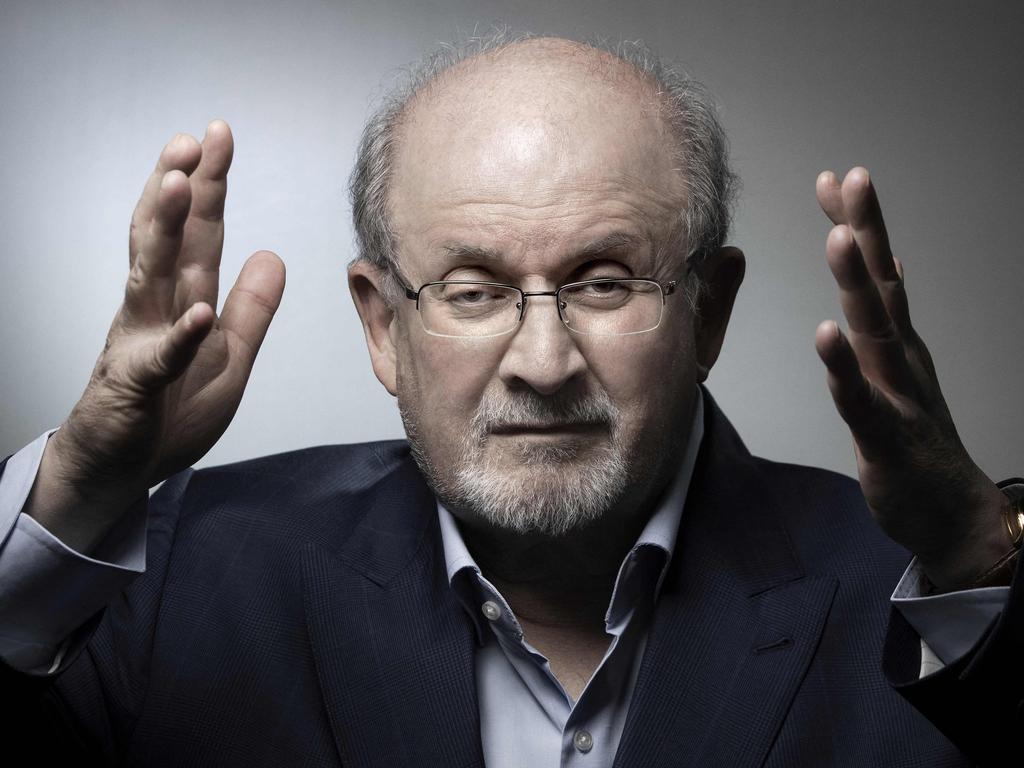

Following the attack on author Salman Rushdie, the writer of Chocolat is at the centre of a row which has split the literary world down the middle.

Wars break out in August. In the literary world hostilities have erupted, conducted with maximum force by open letters and tweets. Let’s call this present conflict the War of the Chairpersonship of Joanne Harris.

Harris is best known for the mighty bestseller Chocolat, her lush 1999 novel, which was turned into a film starring Johnny Depp and Juliette Binoche. But she is also chairwoman of the management committee of the Society of Authors, the 12,000-strong “trade union for writers, illustrators and literary translators”. According to her critics she must leave the post she has held since 2019. In an open letter published on Tuesday, they say her position is “untenable”.

Why? Blame Twitter. It makes intelligent people strangers to sense.

On Saturday, the day after Salman Rushdie was attacked on stage in New York, Harris published a Twitter poll asking if fellow authors had “ever received a death threat (credible or otherwise)”. The answers she provided – “Yes”, “Hell, yes”, “No, never” and “Show me, dammit” – were frivolous given the circumstances. Even Harris thought so, deleting it, then asking the same question in a more sober way. What provoked the furore was that it was seen as a dig at JK Rowling, who had gone public that day, saying she had received at least one “you’re next” death threat on the social media platform after Rushdie’s stabbing.

The subtext to all this is that Harris is a passionate critic of gender-critical feminists, and Rowling is now the most high-profile “Terf” (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) in publishing. Harris, 58, who lives outside Huddersfield, works in a writing shed that is scattered with pink fluffy cushions, which does not conjure up an image of a cultural warrior. She has been with her husband, Kevin, since they were both 16, and they have one grown-up child, Fred, who is trans.

Rowling first fell foul of TRAs (trans-rights activists) in June 2020 when she took issue with an article that referred to “people who menstruate”. She wrote in a well-considered series of tweets: “I know and love trans people, but erasing the concept of sex removes the ability of many to meaningfully discuss their lives. It isn’t hate to speak the truth.” Abuse and threats followed. Some burnt her books in disgust.

Matters reached a new low on the moronic inferno of Twitter in September 2020 when Troubled Blood, Rowling’s Cormoran Strike detective novel, was published. It features a serial killer who occasionally dresses up to commit his crimes – but a review published before the reading public could see the thriller for themselves described the villain as a transvestite. Cue outrage by those already primed to be outraged. The #RIPJKRowling hashtag began trending. Rowling received further death and rape threats.

One wing of the literati swung into action with an open letter saying: “JK Rowling has been subjected to an onslaught of abuse that highlights an insidious, authoritarian and misogynistic trend in social media. Rowling has consistently shown herself to be an honourable and compassionate person, and the appalling hashtag #RIPJKRowling is just the latest example of hate speech directed against her and other women.” It was signed by Ian McEwan, Sir Tom Stoppard, Dame Susan Hill and Lionel Shriver.

A counter-letter appeared four days later, which though it did not mention Rowling, was clearly aimed at the Harry Potter author and her supporters. “Non-binary lives are valid, trans women are women, trans men are men, trans rights are human rights,” the letter said. Its signatories included Jeannette Winterson and Harris. Harris believes that the current criticism of her is because she came out as a supporter of trans rights.

The latest critical open letter – there is a counter-letter supporting Harris doing the rounds too – argues that “in light of the shocking attack on Sir Salman Rushdie, we, the undersigned writers and industry professionals, wish to express our deep disquiet and anger at the Society of Authors’ abject failure to speak out on violent threats towards its members, and the behaviour of Joanne Harris, the Chair of your Board of Management, on Twitter.”

The letter continues: “It has been clear to many of us that the Society of Authors has been captured by gender ideologues who brook no debate and who are not prepared to support authors who fall foul of online bullies.” Katharine Quarmby, a former member of the Society of Authors’ management committee, said she raised the death threats against Rowling in 2020 and 2021 and asked that the society put out a statement condemning them. “This did not happen and has not happened since.”

Harris’s critics claim that the Society of Authors can hardly act as a trade union if it won’t swing into action to protect writers who don’t have the “correct” views. Harris says she supports anyone regardless of their beliefs. Writers such as the former children’s author Gillian Philip disagree. Philip, a writer of fantasy novels, was dropped by her publishers after publicly agreeing with Rowling. She is now a lorry driver. “The haulage industry is far more supportive and inclusive, and a lot less misogynistic, than the world of children’s writing,” she said.

Talk to feminist writers and you hear of book deals rescinded, events cancelled, manuscripts rejected. Talk to older publishers used to such liberal-minded ideas as publishing books you don’t agree with and they are now much more cautious about what they are willing to publish. A powerful example of this new creeping self-censorship can be seen in the comments made by Philip Gwyn Jones, the publishing director of Picador which published Kate Clanchy’s Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me, which was criticised for using “racialised stereotypes”. After the furore he told The Daily Telegraph: “I do worry about some of the younger generation [in publishing] needing to … politically or morally subscribe to every book they are involved with … At its most extreme, it can be limiting and even totalitarian. That’s to be resisted.”

He was soon forced to apologise, Maoist-style, on Twitter: “I now understand I must use my privileged position as a white middle-class gatekeeper with more awareness to promote diversity, equity, inclusivity, as all UK publishing strives to put right decades of structural inequality. I believe in the necessity of this change.” He is no longer Picador’s publishing director.

It is strange that a writer so singular as Harris should be so sceptical of cancel culture, a phrase that she puts in “scare quotes”. She has always had a reputation for being independent-minded, and has done well by doing things her way. In 2012 it was revealed that Harris had become only the fourth British female novelist to top one million sales thanks to the roaring success of Chocolat. Rowling was one of the other three (though at that point eight of her books had topped a million sales).

Harris’s recent books have sold well, perhaps thanks to her unwillingness to bend with literary trends – she has tried her hand at mythology, vampires, gothic horror, cookbooks, short stories, magic realism. Her latest novel, A Narrow Door, is set in a school, drawing on her experience of teaching French – her mother was from France – for 15 years, latterly at the independent Leeds Grammar School.

Her child perhaps explains why she holds some of her positions so strongly. The trans issue must have a personal edge. Fred is a 29-year-old freelance editor whose Twitter handle announces, jokingly: “Undeclared trans in the bagging area.”

This week Harris tweeted: “I’ve known he was trans for awhile, but he came out publicly on June 1st, which is why I haven’t mentioned it before … Anyone using him to attack me is utterly and forever beneath contempt … You want to come for me? Do it. I’m right here.”

Not all of her 168,000 tweets are as combative as that but you can’t help reach the conclusion that deleting Twitter from her phone would be a useful first step to bringing about a ceasefire.

The Times