Harry Potter was born 25 years ago this week — it has changed so many lives

Like magic, Harry Potter saved JK Rowling’s life. Twenty-five years on, this is the extraordinary true story of how it became a global phenomenon.

Like magic, Harry Potter saved JK Rowling’s life. She had had thoughts of suicide and sought help. She made mistakes, and righted them.

Her first marriage was a high-speed train wreck – she wed in October 1992, it was over in 13 months. From this she took away a daughter, Jessica, and three chapters of a book that, four years later, would be published as Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

The first review appeared 25 years ago this week in her hometown newspaper, The Scotsman, and it would have put a smile on the face of any unemployed single mother, even if they spelled her name wrong: “If you buy or borrow nothing else this summer for the young readers in your family, you must get hold of a copy of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by JK Rowley. This is a book which makes an unassailable stand for the power of fresh, inventive storytelling in the face of formula horror and sickly romance.”

We all know what follows. It all should have been so different, but with uncommon lenience, fate beckoned Joanne Rowling to writing after early and teenage years of dreamy apartness and, later, unanchored days of disorder. School was a grind; she was bright but unexceptional and unambitious, reading widely to shy away from an unpromising future. Oxford University rejected her. Appropriately, she moved into a flat in Clapham – whose omnibus is legendarily filled with ordinary, but reasonable men.

Life at home was unhappy for the young Joanne – her mother was ill, her distant father apparently would have preferred a son. That relationship remains strained. They’ve not spoken in years and he sold his first edition of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, given to him on Father’s Day 2000 with the inscription “Lots of love from your first born”. She might have been only a girl, but he made $70,000.

Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, and Hermione Granger had come to her on a train trip from Manchester to London in 1990, but she had neglected to tell her mother of their birth before her mum died on December 30 that year.

Twenty-five years ago this week, Rowling’s first novel appeared, setting off a phenomenon. Six more would follow. The first novel was sent to the office of a little known London independent filmmaker, David Heyman, whose only claim to fame was that his godmother was Diana Dors, the British Marilyn Monroe. Apparently the book with its “daft” title sat on a shelf unnoticed until a secretary read it and told Heyman how good she thought it was.

Heyman read it and agreed. He encouraged Warner Bros to buy the rights. The seven books became eight films and Heyman produced them all. Interestingly, the title of that first book was changed in the biggest market. The US publisher thought the word philosopher was archaic, too English, and would not be readily understood by young Americans. (Keep in mind that United Artists, a company co-founded by Charlie Chaplin, considered releasing the Beatles’s A Hard Day’s Night film with subtitles lest the Liverpool accent prove too much for that same audience.)

By the time a publishing date loomed for the US edition of Rowling’s first book it had already proved itself a winner, so the author had some clout. At first Warner’s considered another title: Harry Potter and the School of Magic. Rowling would not accept that, but she agreed to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Two years ago, Rowling used that clout in her widely read website to support a woman sacked because she insisted that sex was determined by biology. Rowling wrote: “I refuse to bow down to a movement that I believe is doing demonstrable harm in seeking to erode ‘woman’ as a political and biological class and offering cover to predators like few before it.” A rabid storm of protest ensued, and lining up to condemn the author were the young stars who had made their names (and fortunes) from the Potter movies: Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson and Rupert Grint.

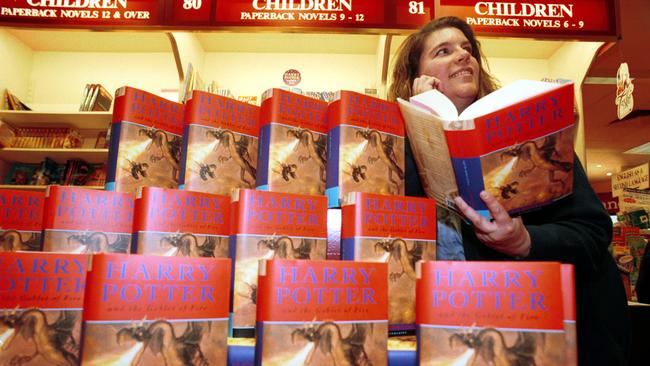

The Bible aside, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is the fifth biggest selling book of all time. It is estimated that Harry Potter books have sold 600 million copies and have been read by many more. In the English-speaking world about a third of us have read at least one of the books. Twice that number have seen a Harry Potter film. The films have earned just shy of $14bn.

Of course, because the films coincided with Peter Jackson’s trilogy depicting JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the two have been endlessly compared. And there is no denying Rowling’s creation has moments that are pure Tolkien.

Both have modest heroes – Harry Potter and Frodo Baggins – but then do so many of the great novels. Frodo has The Ring, and it makes him invisible but comes with burdens; Harry has the Cloak of Invisibility. Frodo had Gandalf in his corner while Harry has Dumbledore (Tolkien’s Tom Bombadil poem mentions “Dumbledors”, a primitive term for bumble bees). There is Wormtail and Wormtongue, Kreacher and Gollum, Dementors and Ringwraiths.

Head to head at the box office, Harry won hands down. But the Potter films were nominated for 12 Academy awards and won none. The Lord of the Rings series was nominated for 30 and won 17, the final instalment winning 11, including best picture.

While Tolkien’s tale may seem more enduring, not everyone would have it that it is superior, including John Carroll, a professor of sociology at Melbourne’s La Trobe University, and a contributor to this newspaper.

The Harry Potter books are serious “works of literary merit – and extraordinary feat of imagination,” Carroll says.

“They are just so rich and vivid. It’s sold 600 million copies. Eight-year-old boys who would never read a book are reading 800-page JK Rowling novels,” he said.

“And it’s not easy prose. She has a very big vocabulary, the grammar makes no concessions to young readers. She has made an extraordinary contribution to a young generation in the age of smartphones. They’ve every reason not to read books. She’s got them reading books. In their millions. And re-reading them, watching the films.”

Carroll believes the films are excellent and in no way detracted from the reading experience.

And, perhaps controversially, he believes Rowling’s works superior to Tolkien’s.

“I think they’re much better. It’s a much richer cast of characters. I think there a much more vigorous and varied narrative thread throughout the seven volumes of Harry Potter – it’s much longer for one thing. Lord of the Rings is mediocre to me next to Harry Potter.”

And no one since has replicated the success of Harry Potter, so it can’t be that easy.

“No, it’s unique and it will continue to be unique, I think,” said Carroll. “It’s an extraordinary feat of the literary imagination. Enid Blyton wrote lots and lots of stuff, but there’s nothing like the size of this single work.”

Carroll observes that Rowling engages with her young audience like never before. “From about No.3 onwards they are more and more just about death. The threat and fear of death. Even Harry’s nickname – the Boy Who Lived – underlines that – and Voldemort’s got “thief of death” in his name. And this is gobbled up by children.”

Carroll believes the generations that grew up reading Harry Potter will go back to it later in life, not to relive their childhood but to re-experience that world. “There is already evidence of 30-year-olds going back to it,” he said.

“If you read seven volumes of that size and you get a habit for reading, it inevitably spills over. What the figures do show (is that) children’s book are still doing very, very well, but there’s a plunge in reading for pleasure.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout