Why we need the classics — and must strive to teach them

God, spare us the cancellers. Shakespeare, Dante, Homer… they represent all the varied riches of life.

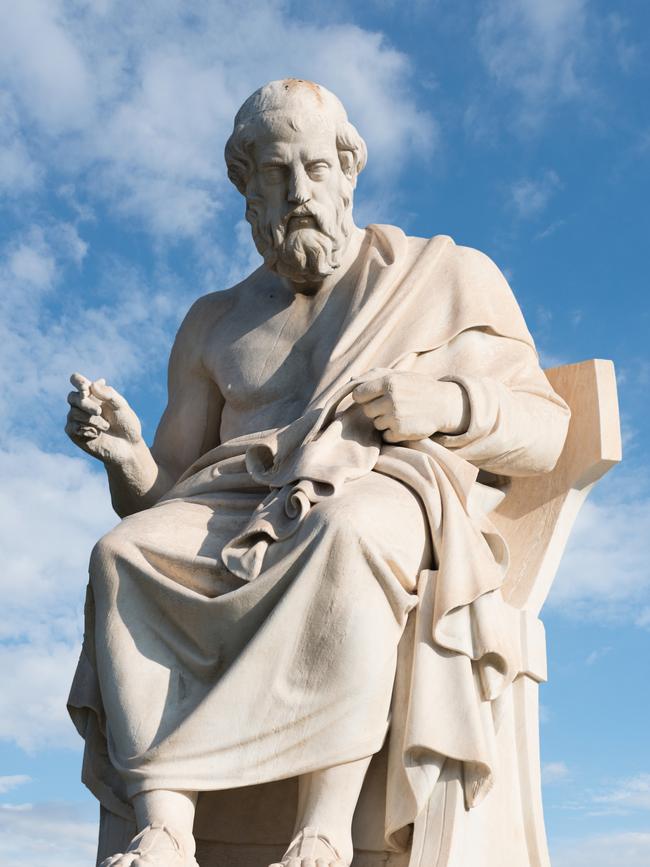

Why are the classics of our literature – indeed of any art form – important, and why should we strive to teach them? The simplest answer to this is to say, in the manner of Henry James, it’s because of the depth of life they represent, the moral aspect of literature by which we recognise it as a symbolic form of truth, or, in the case of philosophy, an explicit engagement with human understanding via the practice of argument, bearing in mind the expressive complexity of this in the case of one of the greatest and most “literary” of philosophers, Plato.

We live in a world pockmarked or bejewelled (depending on which way you want to look at it) with value judgments and more or less universally accepted valuations, which have proved regnant in Western civilisation for want of a better word – allowing for the concomitant sense of the Musee Imaginaire: the Picasso who painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon knew the power of the African masks.

When TS Eliot wrote The Waste Land – published 100 years ago this year – he could repeat shantih from the Upanishads and gloss it as “the peace that passeth understanding” because he was drawing on the tradition of mysticism in Hinduism and knew of what he spoke. Doesn’t he also place the Bhagavad Gita with Dante’s Divine Comedy among the world’s very greatest religious poems?

Every form of culture we know has been Westernised and that is part of our knowledge of it. Ezra Pound was both an iconoclast and a finder of icons, and the poems from the Chinese he imagined and recapitulated from Fenollosa, a part of that still, vast, tranquil landscape of the Chinese for us.

But we are surely not wrong to think that The Dream of the Red Chamber and Romance of the Three Kingdoms might be classic points of entry for forbidden cities we do not know.

Then there’s that classic from – is it 11th century Japan? – which R.P. Blackmur, one of the greatest modern critics, wanted to write about and adumbrates in the introduction to Eleven Essays in the European Novel.

What a confounding and beautiful thing The Tale of Genji by the Lady Murasaki seems to be. “There was an emperor. He lived it matters not when.” Arthur Waley, who translated its exoticisms with a lush musicality and an exquisiteness of rhetoric, warns that the opening is more fairytale-like than what follows. He tells us that this is as fraught a society, as narcissistic, and sophisticated in its shadings and hair splittings over feeling as Proust, the better part of a millennium later. It’s written when we were listening to The Battle of Maldon. The Tale of Genji at the merest glance, unfinished and unfinishable, as French literary theorist Maurice Blanchot would say, is one of those eye-openers comparable in the reader’s development to the moment when as an adolescent you realised that the Greeks had a modernity – that’s how we first perceive it, erringly – comparable to our own.

When we read Jocasta say to Oedipus, “Many a man has dreamt as much” – in the old E.F. Watling Penguin – we get a shock of recognition that is thrilling. We also experience (more particularly if we have a marked interest in drama) the revelation that a sense of dramatic form, unmistakably tragic in intensity and achievement, can be presented in more or less stark modern English.

If we are used to Shakespeare – and we would be if we had had the usual high-school education of the post-war period – the plain modernity of the language would work to highlight the structural brilliance of the dramatic construction. As W.H. Auden said, any Shakespeare play could be shorter or longer, but the opposite is true of Sophocles, the greatest of all masters of that sometimes despised entity, the well-made play. Not just in Oedipus Rex, which we’ve just cited and which Aristotle took as his template in his Poetics, but in all his plays.

For others of us, the Greeks from Homer down were mingled with modernities. Not long after I hit on The Iliad – first in E.V. Rieu’s very novelistic translation – remember how in Iris Murdoch’s The Black Prince the main character says everyone should first read Homer in an unvarnished translation? It doesn’t stop the mind from imagining what the Reformation period translators would have made of the task of translating Homer, given the piercing elegiac quality of “How are the mighty fallen” or the poignancy of David’s lament, “Oh Absalom, my son, my son, would God I had died for thee, O Absalom my son.” And, yes, together with that, we would want the young to know as much of the Bible as they could come at. The narrative urgency of Samuel and Kings, the deep introspective poetry of the Psalms, the near tragedy of Job, the ironic wisdom of Ecclesiastes and its endless elegiac revelation of vanity of vanities, the erotic splendour of the Song of Songs.

It’s a long time since the late Susan Sontag said, in some sorrow, “They don’t even know the Stations of the Cross”. But some rudimentary grasp of the Judaeo-Christian tradition would be handy for someone trying to negotiate the art of the last six or seven hundred years, just as the classical myths collected by Ovid in a work of poetic genius, Metamorphoses – the greatest single influence on Shakespeare with the possible exception of the historian Plutarch. Scholars say that in Prospero’s “Ye elves of hills” they can tell where Shakespeare was pinching from Arthur Golding’s 1567 translation, adored by poet Ezra Pound, and when he was echoing the original Latin. But the Greek myths are handy. It would be nice if the youth of today could quote and translate at least “Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt” – The tears in things that touch the mortal heart. Or, let’s say, “Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes” – I dread the Greeks, yea, when they offer gifts.

If we’re circling the past 700 years it’s good to remember Dante, the anniversary of whose death was last year. Dante belongs with Homer and Shakespeare as one of the greatest writers who ever lived, and his journey through the realms of the afterlife –– in his Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso –– first with Virgil as his guide, then his beloved Beatrice, has a staggering clarity. Dante is one of those great poets who writes plainly; he writes like the Shakespeare of “Keep up your bright swords for the dew will rust them”. Or the Christopher Marlowe of the Ovid translation: “The air is cold and sleep is sweetest now.”

So we have Francesca, early on in the Inferno, describe the moment when Paolo gives himself to her: “La bocca mi bacio tutta tremante” (He kissed my mouth all trembling). “Lasciate ogni speranza voi ch’entrate” is the original Italian of “Abandon hope all ye who enter here”. And there is the cadenced power of the Temple Classics edition, which has the Italian on the other side of the page. “Amor ch’a nullo amato amar perdona” which means “Love which to no lover permits excuse for loving”. And then ultimately, blindingly, in the face of the three interlocking lights of the divinity, “L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle”. The love which moves the sun and other stars.

One trusts that no one will cancel Dante because of the torture and the Christianity, but you never know. His countryman, the close contemporary of Shakespeare, Caravaggio –– one of the greater painters in the history of the world and a master of chiaroscuro and stage lighting –– is in the process of being cancelled because he supposedly killed someone. How this can possibly have pertinence to his painting, with its sometimes extraordinary use of street boys and the tumult and drama of everyday life, one cannot begin to imagine.

And Caravaggio leads naturally enough, out of some affinity of the spirit, to Shakespeare, even if he’s closest in spirit to a play like Measure for Measure, with its fascination for moral paradox as Angelo lusts for Isabella because of her purity. The play contains that oracular speech of the Duke: “Be absolute for death” which includes that almost Zen-like annihilation of selfhood. “Thou art not thyself for thou exists on many a grain of sand” but Claudio’s “Aye but to die and go we know not where” has an extraordinary vigour in its talk of hugging darkness like a bride; and then there’s Isabella’s “Man, proud man, dressed in a little brief authority”.

It is not as well-plotted as The Merchant of Venice – which is a disguised problem play – but it is at least as rich. The Merchant can appall Jewish people, though it contains the impassioned anguish of “Hath not a Jew eyes”; and that very beautiful line of Shylock’s, “It was my turquoise, I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor” has a depth and a poignancy that you would hope would stop the cancellers in their stride. The way in which anti-Semitism is made to seem normative is devastating even if it’s disturbing.

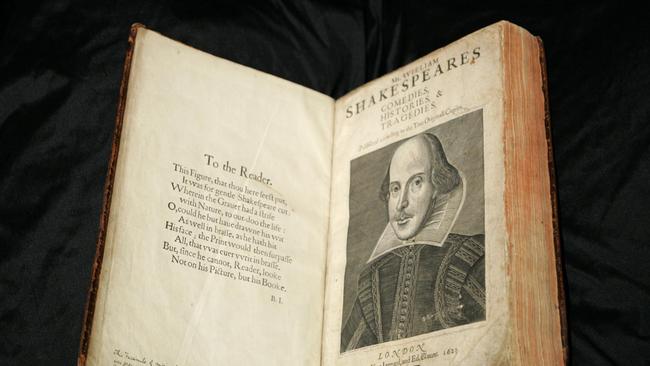

But Shakespeare should be at the centre of whatever way we strive to teach whatever civilisation we have. The history of civilisation is at the same time, as German philosopher Walter Benjamin reminded us, the history of barbarism: Athens executed Socrates and Rome executed Christ and both these events should be central to the story we tell. And Renaissance England, Shakespeare’s England, was an axe-blade world, a world of religious persecution and an exorbitant abuse of power.

When we treasure, as we should, in the lead-up to Shakespeare, such lyrics of Thomas Wyatt as “They flee from me that sometyme did me seek” and “Whoso list to hunt” – they are among the greatest poems in the language – we are also aware of the dissolution of the monasteries, the execution of Thomas More, who wrote Utopia, the fury and bloodshed of establishing a new Gallican form of Christianity in order to consolidate divorce while remaining, as Henry did, a religious conservative.

It’s a good idea, as we come to Shakespeare, to have an attendant awareness of Machiavelli’s The Prince and Montaigne’s Essays. Macbeth is arguably a tragic extrapolation of Machiavelli’s sense of the annihilating conundrums of “virtue”, while Montaigne influences both Hamlet and The Tempest, those twin mirrors of Shakespeare’s art. Shakespeare is a world we must preserve and promote. Think of the moment in Henry VI when Gloucester gives the speech about the chameleon and setting “the murderous Machiavel to school” and we realise we’re already in the presence of one of the world’s great dramatists.

Think of the glory of early Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet with its enraptured representations of young love and the light that breaks from that window. Richard II, which Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, the author of The Waning of the Middle Ages, thought was one of the only genuine representations of that stained-glass world. “Here cousin, seize the crown,” Richard cries to Bolingbroke, of whom he says, “good king, great king, and yet not greatly good”. Think of what Shakespeare had made of a hobgoblin’s vice of a king in Richard III and that extraordinary dream sequence, almost like Dante, which Clarence narrates, “And for a season after could not but believe I had been in hell”. Think too of the sublimity and hilarity of A Midsummer Night’s Dream: an enchanted world “ill met by moonlight” but with Puck setting a girdle round about the earth and all that wonderful comedy when the world of the mechanicals, Bottom and his mates, collides with the fairies and the runaway lovers.

These are four plays you could teach at the start of secondary schools, in Year 7, and we should anthologise the speeches while also teaching the plays with whatever aids, by way of YouTube and film and spoken word recordings, we can muster. The sooner the young learn the thrill of the rhetoric of Henry V (“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers”) and then that contrasting word of Mistress Quickly saying how Falstaff babbled of green fields and cried, “God! God!”, the better.

The latter is a momentary flashback to the world of Henry IV, where Shakespeare complicates forever his sense of comedy and history by creating his greatest comic character but then giving him a heart that is vulnerable to young Prince Hal. Who but Shakespeare could have counterpointed Falstaff, first with the quicksilver dashing Hotspur who would pluck honour from the pale-faced moon and then, in Part II with Justice Shallow, the man with whom so long ago he had heard the chimes at midnight? This is the zenith of Shakespeare’s naturalism.

Where does Shakespearean tragedy come from? Did Shakespeare stumble on Hamlet because he had made Richard II into an actor-prince, a drama queen shattering the mirror of a self he could not stop watching? We have to keep alive the nearly infinite possibilities of how to play and conceive of Hamlet; the extraordinary difficulty of that tragic villain, Macbeth; the gorgeous magniloquence of Othello.

And then there’s the impossible realisation of King Lear. You can see in Lear the impulse towards a purgatorial logic and the possibility of a happy ending that beguiled the 18th century. There’s the “wheel of fire” speech and “we’ll sing like birds in the cage”. All of this is a world away from what he achieved in Antony & Cleopatra – is there a greater moment in the whole of drama than the one in which she says of the asp, “Dost thou not see my baby at my breast / that sucks the nurse asleep?” But King Lear is transitional to the world of the romances, the “mouldy tales” as Ben Jonson called them. There’s the same preoccupation with fathers and daughters: Leontes and Perdita, Prospero and Miranda, Pericles and Marina. Pericles is a staggering work because Shakespeare did not even bother to rewrite the original piece of romance journey work, so it exhibits his late genius the way Michaelangelo presented those figures half-emerging from the stone.

But the romances also show Shakespeare at his most obsessional and his most experimental. Think of that moment when Pericles says, meeting Marina, “I am wild in my beholding”, and declares, “My wife was like this maid”. The language of Pericles is almost baroque, you can see it as halfway to John Milton, but it clearly represents a supreme master, late in his career, doing as he will. “A terrible childbed hast thou had, my dear; / no light, no fire: the unfriendly elements forgot thee utterly, nor have I time / to give thee hallowed to thy grave …”

Of course we need Paradise Lost just as we need that utterly opposite writer, Chaucer. There’s that extraordinary chastity and systematic understatement in Chaucer “Your eyen two wol slee me soddenly, / I may the beaute of hem not sustene” or the end of Troilus and Creseyde “Go, litel book, go litel myn tregedie”.

Of course we need a place for Shakespeare’s great contemporary Cervantes, and it’s instructive to read him in the first English translation done by the Irishman Thomas Shelton (revised, I think, in 1619.) Cervantes is great in any translation but Shelton’s prose comes from before the moment when prose flattened itself for one kind of communicability. The British discovered, when they put it on stage with Paul Scofield as that Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance, the tilter at windmills, that Shelton’s version sounded like blank verse.

Of course Shakespeare illuminates everything in his vicinity. You can see why Canadian critic Hugh Kenner would say that John Donne must have been a lot like Hamlet: this tallies with the very histrionic dash of his extraordinarily great poetry. Jonson, as ever, is the great contrast with both of them. And the greatest of Shakespeare’s contemporaries and successors take fire from him. John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi and Thomas Middleton’s The Changeling are both very great masterpieces.

But God spare us the cancellers. The reasons for cancelling Huckleberry Finn are inane. Huck’s “alright, I’ll go to hell”, is a supreme act of moral courage. American literary critic Lionel Trilling’s account in Jim’s pride in human affection is the definitive liberal response. Heart of Darkness is a parable of colonialism, not a justification. Rudyard Kipling’s Kim is a hymn to the different faces of Indian religion and civilisation.

My own practical business is in evaluating new books. David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld are among the masterpieces that have come my way. One yawning gap with the world of academic’ sometime literature departments is the way they have dropped the ball in relation to contemporary literature. Eliot was not wrong to say that literature was a timeless order modified by every subsequent work of literature, however much this bit of philosophical idealism may be a hard saying.

It should be apparent that great works have been produced that universities have done little to assimilate. Williams Gaddis’s The Recognitions and JR (“Money in a voice that rustled”) are in this category, and so are the long poems of David Jones, In Parenthesis and The Anathemata.

In Australia, a previous generation of academic critics did everything in their power to establish the greatness of Patrick White’s work, which is on par not with Proust and Joyce but with Faulkner and Nabokov and Beckett, and the same is true of Christina Stead in The Man Who Loved Children. Although similar efforts have gone into highlighting Les Murray’s poetic genius, the light is flickering. Yes, Gerald Murnane is seen as a great writer, with those infinite modulations of colour and tone like a Rothko painting, but how long will this perception last?

It’s not hard to wonder about Roberto Bolano or Elfriede Jelinek in The Piano Teacher, Thomas Bernhard in everything. We need constantly to be aware that literature can be a difficult pleasure, something that was not forgotten in the wake of modernism.

We need to be our own library of Alexandria and resist the flames flickering all around us.

This is an edited extract of Peter Craven’s recent Ramsay Centre lecture, Classics: Why we must keep them alive.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout