The book is under assault

Encyclopedias, atlases, and dictionaries are disappearing. Generations are now growing up ignorant of the stories through which their ancestors gained an understanding of life’s vicissitudes.

Is the book under threat? If so, does this matter? Surely, the sight of teenagers, not to mention their elders, spending as much of their waking lives as they dare on their mobile phones should give us pause.

Obviously, the book is under assault for the attention of the Western mind from online reading and chitchat. Google has made a swath of traditional books obsolete. Encyclopedias, atlases, and dictionaries are disappearing, and many overview guides of history, biography, and literary criticism are becoming dusty unconsulted relics, whether they remain useful sources or not. Bookshops disappear. On public transport, where once commuters would read romance novels, today most live on their smartphones. Many university bookshops went, over 20 years from the 1990s, from being richly and broadly stocked, with textbooks in the small minority, to becoming little more than gift shops spotted with narrow functional course guides, if that. Mind, this was less to do with emerging online habits than humanities’ academics losing their nerve in setting books for their courses, as their authority within the academy diminished, and with it the power to run courses as they wished.

On the other hand, book sales remain solid. According to Nielsen Book Data, Australian print book sales rose steadily until 2010, declined slowly over the next seven years, then recovered to 2010 levels during the pandemic. Pandemic reading has favoured escapist fiction especially crime, self-help and children’s books. Serious nonfiction has struggled.

In the early days of the e-book many prophesied that the end of the printed version was nigh. But e-book sales plateaued. It seems that for most, in most situations, a preference endured for the tactile pleasure of the solid object, and the ritual of turning pages. Bookshops report new generations of younger readers buying books – a fact that distinguishes them from print newspapers and the ABC, largely dependent on a dwindling, ageing population of devotees.

The key marker in the book’s favour is its authority. The Bible is not just the catalogue and repository of Western religion, but the commanding symbol of authoritative truth. The belief endures, however often misguided, that if something is written in a book it has to be true, compared with something as ephemeral as a passing flash of online information, or even a newspaper article, skimmed one day, lighting a fire the next.

Cookbooks illustrate. Their sales have continued to thrive. In purely rational terms, one might expect that in a crowded and messy kitchen, a recipe read on an iPad, or even a smartphone, would be more practical. But some special aura seems to surround the printed word as contained in a large and weighty, hardback book which is stylishly designed and illustrated. In this domain, the object, in its very facticity, is preferred.

The significance of the book is a separate matter from its current uncertain popularity. Our culture is itself a living library, carried by the book. Classical Athens marked the transition from knowing Homer and the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides through oral transmission – performance – to reading the authoritative texts on papyrus scroll. Euripides was known to have had a large library. Alexander the Great always slept with his copy of Homer, edited by his teacher Aristotle, under his pillow, as he crossed much of the known world, founding 70 cities, carrying his missionary ideal of Greek culture with him as he went – an ideal deriving from that culture’s Bible, The Iliad. Even in Palestine 300 years later, Alexandrian Hellenistic culture was predominant – the Gospels being written in Greek.

The English language today, at its most fertile and pungent, is largely the creation of two books, the King James Bible and Shakespeare, complemented by the Book of Common Prayer. Almost the entire literary canon that has followed, from the early 17th century on, has been shaped by their presence. And that presence has been reflected far beyond the canon, from standard marriage vows to the speeches of Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill.

The pre-eminent book in the wider Western tradition is the Bible. Jesus himself was a creation of four stories, with negligible evidence about his life, or even that he lived, outside them. He is the product of a text. The thousands of magnificent churches and cathedrals that grace the Western world are projections from that same text, as is much of the greatest of Western art, from Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Donatello’s Magdalene, to Raphael’s Sistine Madonna and Transfiguration, to Michelangelo’s Moses, Poussin’s Autumn, Bach’s Passions and cantatas and Mozart’s religious music.

There may be a more profound indebtedness to the book. George Steiner argued in a 1985 essay titled Our Homeland, the Text, that the Jewish home is in the text, not in a physical place, Israel. The Jews, through centuries into millennia of persecution, of being repeatedly expelled from where they were living, into a state of near permanent uprootedness, survived because of the Torah – the Hebrew Bible, the voluminous works of interpretation that flowed from it, and the Law that was inscribed in the holy writings. There was such commanding authority within the texts, binding the people together in a shared self-understanding and mission, that they developed an indomitable inward-looking character and resilience that could withstand their outcast condition of near permanent exile.

The very exclusion from the normal communal activities of village, city, and country, including politics, may have contributed to the vitality concentrated on religious observance and learning. Pre-eminent veneration for the scholar and the book followed. It has been speculated that the extraordinary contribution of secular Jews over the last century and a half to Western science and arts, the professions and business, has come from the release of suppressed energy built up over generations, formed by prodigious reserves of mental discipline and inward concentration.

The other rich cultural source for the rise of the West, Athens, ran parallel with Jerusalem in its dedication to knowledge and truth. The Greeks created the epic drama, the tragedy, comedy and satire, philosophy, anthropology, history, and much of mathematics and science as it has come down to us – all transmitted by text. They built the first great library, in Alexandria.

The authority of the book has often worked in negation. Since Babylonian times, books that were considered powerful enough to inspire treasonous or blasphemous acts have been burned. Major book burnings through history have been common and include Muslim attack on the Library of Alexandria, Luther burning Catholic edicts and texts, Spanish Inquisition destruction of heretical, especially Protestant writings, and the widespread 1930s German burning of mainly Jewish writings.

The book in the online age has retained, perhaps surprising, powers. Recent studies across many countries are showing that the best predictor of adult success in life is the single factor of child reading engagement and ability, often correlating with the number of books kept in the home. It is not the more commonly assumed influences of quality of school attended or the socio-economic status of parents. Parents today would be better advised to spend their energies trying to foster a love of books in their children, rather than worrying about the credentials of this school or that. What is a genuine worry is that, over the last 20 years, reading books for pleasure has dropped off precipitously as children enter their mid-teens.

At issue in the singular importance of reading, I suspect, is not just fluency in manner of phrasing and vocabulary. The cadences of speech and the rhythms of language help frame the way the world is seen and interpreted, through the critical developmental period in which the mind and its imaginative capacities are being formed. Further, thinking in a logical, orderly manner draws on blueprints of how to develop an argument or a narrative thread, more amply experienced in reading a book than in short texts. However, serious reading is a solitary, meditative endeavour requiring time and silence, all of which is under pressure from the hectic noise and restless urgency of online culture.

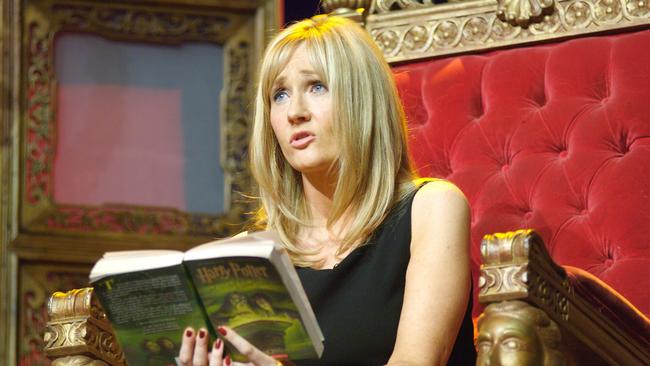

Maybe the greatest current hope for the book is children. Sales of their books continue to boom. It is not just romantic nostalgia to admire the 10-year-old tucked up in bed at night with a book. Here, JK Rowling’s influence is hard to overestimate. Worldwide sales of Harry Potter are in the order of 600 million. There was the astonishing sight of long queues of children lined up to get the next volume when released, some of whom had slept near the bookshop doors overnight. Moreover, excellent film versions have not eclipsed the original books.

And the Potter texts are difficult, making no concessions to young readers, in either vocabulary or syntax. How many million eight-year-old boys who might otherwise never have voluntarily taken up a book in their lives, now devour 800-page volumes? One may hope that for many, a lifetime habit has been established. Imaginations have been fed from a cornucopia of themes and characters, including deeply serious questions led by the motif, as Rowling’s seven volumes develop, of death, its threat and possible overcoming.

The gravest context today for celebrating the Harry Potter phenomenon is the absence at the centre of our culture: I mean, familiarity with the Jesus story, and with it, the treasure trove of archetypal Old Testament tales ranging from Abraham and Isaac to Joseph’s travails and the Moses saga, a corpus fundamental to the Western imagination. Generations are growing up ignorant of the stories through which their ancestors gained an understanding of life’s vicissitudes, from birth, through growth, to setback and triumph, joy and tragedy.

The ominous, indifferent silence that has descended over The Bible today has spread. In the contemporary university, it has been followed by a turning away from the secular classics, from Plato to Machiavelli, from Jane Austen to Henry James. There may be something to the 19th-century anxiety, expressed eloquently by Dostoevsky, that the death of God would bring in its wake a profane contempt for Raphael, and all he symbolised in the mainstream of Western high culture. This degradation is illustrated today in art that has no higher ambition than to shock and to smear. There is congruence here with George Steiner’s fear that the this-worldly politics of Israel, with its necessary mundane challenges and moral compromises, might erode the spiritual strength of the Jews.

I am more optimistic, but only in the longer run. Serious engagement with the great classical texts, secular and religious, comes in historical cycles. The Bible endures. It will always be there, as will, in English, the magnificent language of the King James translation. Shakespeare is still a vital presence, in schools, on stage, and in film. One side benefit of new technology is that books can now be printed at the press of a button, single or multiple copies, meaning that titles are available that would have previously gone out of print.

Above all, there is widespread inner yearning to know the deep truths about the human condition. Harry Potter illustrates. It will endure long after the passing of the political idiocies of the moment, such as its author has suffered from.

My own experience teaching the old masters of Western art to generations of students, most of whom were secular and with little knowledge of the sources, was that they would respond quickly even to Christian stories, once the eternal themes of mother and child, life calling, flawed character, hope and envy, hatred and cruelty, death and its possible meaning, had been unpacked. As long as teaching took on the big life questions, students would become deeply engaged. Once having entered the realm of serious inquiry, the path back to the book brightens.

John Carroll is professor emeritus of sociology at La Trobe University.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout