Robert ‘Nosey Bob’ Howard: hangman who went down swinging

When capital punishment is legal, a judicious killer is required. What sort of person could do such a thing? Robert Howard took his job seriously.

If capital punishment is legal, then a judicious killer is required. It begs the question: what sort of person could do such a thing? Perhaps more importantly, what does it do to them?

The most notorious hangman in Australian history was Nosey Bob, active in New South Wales for 28 years. During that time he dispatched 61 men and one woman.

Thus he had a public servant job, which came with a pension. He was also the object of horrified fascination, not least because of his appearance: Nosey had no nose.

The mutilation was due to a horse-kick, said the press, and it rendered Howard unemployable as a cab-driver. He had a family to support, and needed a job with security, no matter how unpleasant. Previous hangmen had begun by flogging convicts, or were criminals themselves. Usually they did not last long, the job driving them to drink.

Howard was unusual in his longevity; and as Rachel Franks notes in a book-length study of his life, he was hardly a common hangman. He showed humanity, in a period of legal and cultural transition. No longer did the Bloody Code rule, with frequent hangings as pop spectacle. Charles Dickens found them “inconceivably awful”, due to the “wickedness and levity” of the spectators. Due to agitation by Dickens and others, judicial killing went behind jail walls, with even campaigns for abolition.

Howard also took his job seriously. A successful hanging is a dark art, requiring skill. Slow strangulation, even for monsters, is eschewed, the ideal being a clean neck fracture. To achieve it requires calculations as to weight, and length of rope. With a drop too long, heads could roll. It might be quick, but decapitation was messy, and tended to upset the attending journalists.

Accounts survive of Howard carefully preparing his ropes. He also dressed like an undertaker, expressing his regret to the condemned. Even Abolitionist pressmen found him convivial, verging on media tart. Yet the price he paid was ostracism, having to train his horse to go down to the pub to fetch his liquor. He dealt with his unpopular job with resilience, being a devoted family man. For hobbies, he gardened, invested in real estate and fished, being hell on sharks.

In telling this story, Franks has several major problems. Howard could sign his name, but was otherwise illiterate. He left no personal documents, far less diaries or letters. Franks’ impeccable archival research helps, but what is known of Howard comes mainly via profiles in the sensational press, such as Truth. His job defined him, as did his disfigurement – otherwise his life would not make a biography.

A 400-page book requires a narrative structure, and here the information is organised chronologically. It comprises a life as told in 62 deaths, Howard’s “patients”. To read them is a Newgate Calendar of colonial infamy. People got drunk, lost their temper, committed robberies which went wrong, or baby-farmed (lethal childcare). Not only murders were capital offences: though all-male juries were reluctant to convict, rapists too got the rope.

Howard thus dealt with the Mount Rennie Outrage, larrikins in a gang rape. He hanged Chinese people, and Indigenous outlaws such as Jimmy Governor, and some who seem in retrospect innocent. The one woman he “scragged” was Louisa Collins, called the Borgia of Botany. Others in his line refused to work with women, with Melbourne’s Thomas Jones preferring to cut his throat rather than hang baby-farmer Frances Knorr.

With Collins, the execution went wrong. “Nosey” told the Sunday Times in 1896 that he was holding her up as she stood on the trapdoors, and that without him she would have fallen.

“I could not leave her,” he is recorded as saying. In fact, the trapdoor jammed, and when Collins finally fell, her head got partially severed. Even an experienced hangman could make mistakes; and while Howard’s record was good for his time, some of his patients died with great suffering.

The cumulative effect of this book is that the reader becomes almost inured to the slaughter, death after death. The point is made that hanging is inhumane, distasteful even in agitprop, no matter what the political allegiance. So is capital punishment, so wisely abolished in this country.

What Franks crafts here in this valuable book is a chronicle of colonial crime.

It is also an acute character study of a man with a uniquely degrading job. Howard took lives for a living, but did not let it destroy him. His stoicism and kindness were admirable; and yet the horror persists.

Perhaps the ultimate argument against hanging is that Howard remains someone with whom few would care to drink.

Lucy Sussex is a writer, editor and researcher.

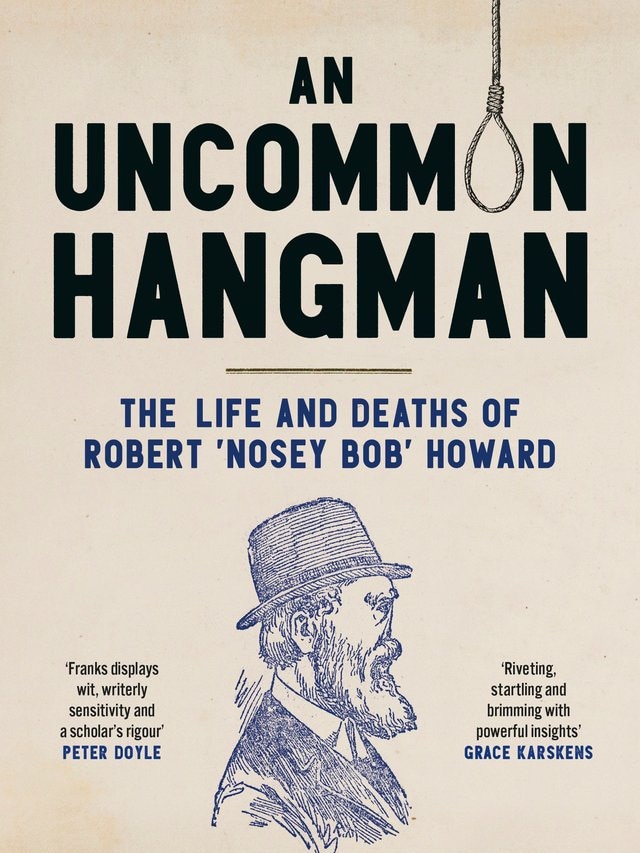

An Uncommon Hangman: the Life and Deaths of Robert ‘Nosey Bob’ Howard

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout