The real estate showman-turned-reality television star had won the 2016 election in unexpected and shocking fashion. He had lost the popular vote to the firm favourite, Hillary Clinton, but thanks to the vagaries of the US constitution had won the electoral college and the presidency.

His enemies claimed he had been propelled into office with the help of Russian intelligence and was an illegitimate president, even a traitor.

Ten days before his inauguration, details of the infamous and mostly fictional dossier on Trump’s Russia ties compiled by the former MI6 agent Christopher Steele, including the story of the so-called “pee tape” recorded in a Moscow hotel, had been leaked to the press.

The day after the inauguration Washington was host to a march by tens of thousands of women, many of them in pink hats topped with imitation cat’s ears, a demonstration intended to convey a posture of collective feminist defiance towards the new president, after his graphic description, caught on tape, of how he liked to engage with women.

Much of Washington, the Democratic Party, the nation’s cultural leadership and especially most of the media – the grand viziers of the American establishment – were ready to resist and even repel this usurpation of power by a man they believed to be a bigot, a charlatan, and most of all deeply un-American; an affront to the nation they believed was theirs.

When, four years later, Trump was defeated by Joe Biden, and even more so when his supporters tried and failed to overturn the result in the January 6 Capitol Hill riot, it seemed like the vindication of the resistance. The alien invasion had been successfully repulsed, the country reclaimed for its rightful leaders.

Eight years after that first inauguration and four years after his successor’s – which he boycotted – Trump is back. Not this time as the pretender in a resisting Washington, the alien usurper of sacred soil. This time he is back as the undisputed ruler himself, riding into a subdued and defeated capital at the head of a new establishment of assorted Republicans, MAGA devotees and Silicon Valley chieftains.

For years now serious commentators have wondered whether America, its tribal partisanship conducted in increasingly intolerant and rancorous terms, might be descending into all-out domestic conflict. Instead, we have the outcome of a (mostly) bloodless civil war, which the rebels have won. When he takes the oath of office, the new model army Trump leads will be in control. This time his election is no temporary aberration. The old regime has signed the surrender papers.

As with all post-war settlements, not everyone is happy with or even fully resigned to the advent of the revolutionary new order. But there is no organised (or unorganised) effort to unseat it. Resistance is futile. Or, at least for the moment, quieted.

The new reality – of Trump’s ascendancy and his opponents’ quiescence – was on vivid display last week at the funeral of one of his predecessors, Jimmy Carter. Trump, denounced by Democratic leaders for the last few years as a fascist, a would-be dictator, sat with the ex (and soon to be ex) presidents, three of them Democrats – Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and Joe Biden – and one Republican, George W Bush, whose disdain for Trump is almost as pronounced as that of any Democrat.

In the pews, Trump chatted and smiled with Obama, the man many still regard as the leader of the Democratic-led establishment. It turns out, according to very reliable sources, that the two men were merely comparing notes on their favourite golf courses, Trump of course explaining exactly why the properties he owns were the best in the world. But the imagery was still powerful.

Obama has told friends the time for resistance is over (even if, by her notable absence from this month’s events in Washington, his wife Michelle is less willing to make a public peace with the new regime).

So when Trump becomes the second man in American history, after only Grover Cleveland in 1893, to be inaugurated for a second presidential term after having been previously defeated, he will take office with unusual authority, a mandate not simply for change but for a new political dispensation.

All presidents change history by virtue of what they do in office. But some presidents change history by dint of their very election; their popular success represents a fundamental shift in the American electorate’s values and aspirations. Trump’s second victory is in that category. His outright win – the first Republican who was not an incumbent to win the popular vote as well as the electoral college since Ronald Reagan in 1980 – and the broadbased nature of his support across ethnicities and geographies reflect a country already demanding a new direction from not just the Biden years but from the bipartisan liberal order that preceded Trump, a rejection of progressive orthodoxies that have driven not just politics in the past four years but the life of the nation.

Americans have turned their backs on much of the globalisation the West had followed since the end of the Cold War: open-border immigration policies, ambitious intergovernmental agreements and national regulations in pursuit of green energy goals, multilateral co-operation through institutions in international security. America First has kicked away all the pillars of the old order, not just in America, as we are seeing in electoral outcomes around the world.

America’s submission to Trump represents also an important cultural moment, a sharp turn away from the race, gender and sexual identity obsessions that have held sway in social and corporate protocols, and have even redrawn the permitted boundaries of language and expression.

As Christopher Caldwell, a conservative commentator, writes in the New Statesman this month, Trump’s victory marks the dawn of the anti-woke era. “While woke did not arise under the Trump administration, it was during its course that it reached a climax: #MeToo in the first year of his presidency (2017); Black Lives Matter in the last (2020) … All Americans, Republican and Democratic, have been surprised by a revolution that is social more than political. They find themselves somewhere in the long, slow process of learning to be a free people again.”

The election of this unapologetically bombastic male, and the elevation with it of people such as Elon Musk and Joe Rogan, can even be seen in part as the reassertion of traditional gender roles and repudiation of what the writer Heather MacDonald has called the feminisation of American culture.

But even presidents whose very election represents an historic shift must, in order to succeed, execute in a way that embeds that shift in the national consciousness, as Reagan did in the 1980s with his radical program of shrinking government and freeing up the animal spirits of capitalism. And here the contrast with Trump’s first term will again be significant.

His rejection by the Washington body politic eight years ago was a foretaste of his presidency. The Russia story, amplified by a hostile media, reverberated for years, forming the basis of a vast federal inquiry into Trump himself, an investigation that ultimately found him innocent of the charges of collusion with Moscow. He was later impeached over another scandal, faced constant leaks from the permanent bureaucracy his administration was supposed to lead and was hounded by an adversarial press.

The resistance effort is muted

This time, though, just as there will be no pussyhat march and no special counsel investigation, there will be no real sustained campaign to destroy him. Most of the media, despite a little hyperventilating about a new friendliness from the Big Tech crowd who control some of the big platforms, will remain adversarial, as they should in a democracy.

But the resistance effort is muted now. So Trump has an unusual opportunity to embed the values his election represents by implementing an agenda that will change the course of the country, and the wider world.

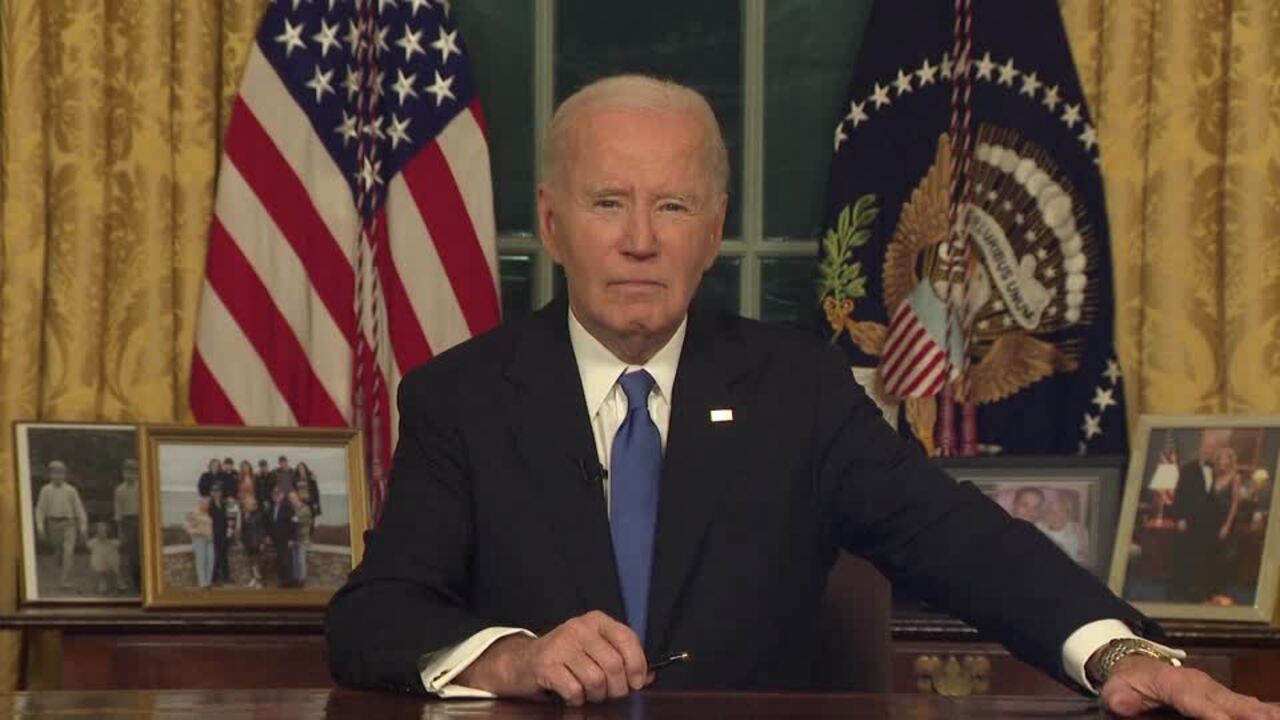

But while circumstances are propitious for a Trumpian populist revolution, two questions tower over the moment: Does he have the skill and self-discipline to seize that opportunity and turn an electoral majority for him and his party into a true change of political direction for the country? And does Trump’s ascendancy bode ill for democracy? With his party brought to heel, opposition cowed, a media sidelined, does America face a decisive turn to a soft totalitarianism, what Joe Biden in his farewell address this week claimed was a new oligarchy, as powerful business interests collude with an authoritarian political leadership to the detriment of Americans’ freedom?

On the first, the early evidence is that Trump already seems more disciplined and focused on executing this time around than in his first administration. That government was characterised by a circus-like quality with a carnival barker at its centre. Key positions were filled by established Republican luminaries many of whom had ideas and plans very different from the president’s.

This time around Trump has assembled a personally loyal team committed to doing his will. As one observer close to him told me this week, his key cabinet and other appointees have been chosen in part because “they’re not going to go off and do their own thing”.

And Trump aides have already indicated that on Day One, Monday (January 21, AEDT), the president will hit the ground with a ferocity of purpose. He is set to issue a slew of executive actions, a strategy of “shock and awe” across a range of policy areas. These will include immediate measures to clamp down on illegal immigration and begin deporting illegal migrants already here, beginning with those convicted of crimes.

There will be measures to expand oil and gas production and bolster US energy supply to generate growth. He is expected to announce various measures to roll back the woke cultural hegemony, banning biological men from competing in women’s sports and ending the promotion of gender ideology in education and the military.

His foreign policy team have been instructed to get to work quickly on bringing a settlement to the Ukraine war. According to one senior foreign policy specialist close to Trump, this could include getting Ukraine to agree to give up eastern parts of the country to Russia, at least temporarily, a move they say would enable Trump to go to Vladimir Putin with an ultimatum: accept this or face intensified US support for Kyiv.

Expect more creative, and doubtless destabilising, threats as part of his signature negotiating style. His warning about annexing Greenland is designed to persuade Denmark to grant the US access to mineral and other rights there and to permit an expanded US military presence to strengthen its posture in the Arctic as part of its global tussle with China, which has been expanding its own reach there.

The same applies to his pressure on Panama over the canal. Trolling Canada about being the 51st state is designed to get Ottawa to lift some of its trade practices. There will be similar threats to the EU and pressure on NATO to deliver more military spending. Despite Trump’s sentimental soft spot for Britain (and the royals), the Starmer government will not be immune to similar economic and defence pressures.

But we can overstate Trump’s ability to get things done, even in this moment of revolution. Domestic politics remain riven. Although he is the first Republican in 20 years to win the popular vote, his victory over Kamala Harris was narrow, just 1.5 percentage points. Republicans won seats in the Senate, yet their majority there is still just 53-47; in the House of Representatives they lost seats and are left with an impossibly thin margin of 219-215.

Economic constraints will matter too. His three major economic initiatives – a big tax cut to renew the cuts originally implemented in 2017, tariffs on imported goods, and sharper restrictions on immigration – each present serious economic risks.

The US fiscal deficit has ballooned to nearly 7 per cent of gross domestic product and there are signs in financial markets that, with inflation persisting, the tolerance of investors for more government debt may be waning.

Tariffs will hurt American consumers and could inaugurate global economic warfare. Tough restrictions on immigration, let alone mass deportations, will limit labour force expansion, a vital component of growth.

Fears he will abuse federal law

There are of course legal constraints to Trump’s authority too, and it’s here where his critics’ darkest warnings about democracy will be tested.

They fear an emboldened and empowered Trump will squash dissent and silence critics using the long arms of law enforcement. The choice as FBI head of Kash Patel, a MAGA firebrand who has talked of criminally prosecuting government employees and journalists, is seen by some as ominous. (I am told there have been discreet inquiries made by more than one prominent journalist to the British embassy in Washington about the possibility of political asylum in the UK.)

It would be foolish to dismiss the idea that Trump might seek to use the awesome power of federal law to go after opponents – after all he believes, with some justification, that that is what Joe Biden spent four years doing to him.

But fears of a Trump Gestapo knocking down doors of political opponents and reporters in the night are overblown. While political control over law enforcement is a reality of the American system, little things like constitutional rights and independent courts are a firm guardrail against abuse.

What about that Trump-friendly Supreme Court, the ultimate arbiter of justice? It is true that a majority of the nine justices were appointed by Republican presidents (three of them by Trump himself) and that the same court last year found that Trump (actually, all presidents) was immune from criminal prosecution for official acts.

But this is no Trump rubber stamp.

Just last week two of the six conservative justices, including the chief justice John Roberts and Trump’s handpicked Amy Coney Barrett, sided with liberals to deny Trump’s efforts to have his criminal conviction in the infamous Stormy Daniels case thrown out. In other cases in the past year these two have indicated a strong distaste for overweening executive power, a vital check on any temptation by the president to excess.

That will leave Trump himself to answer the most important question of all: Does he want to use this extraordinary opportunity to effect a genuine political revolution, with the opportunity to bring a fractured nation together again around the values that made America great?

Or does he use his moment of unrivalled authority to pursue vendettas against opponents, place his own personal interests and vanity above the needs of the country, and further coarsen and embitter the public discourse?

Given what we know of the man, you wouldn’t bet against the latter. But don’t rule out the possibility that this revolution actually succeeds.

The Times

When Donald Trump was inaugurated as president for the first time eight years ago, the atmosphere in Washington was a little like that of a hostile and restive capital being occupied by an invading army.