How the America haters in our midst go easy on China

Australian opinion leaders, many of them distressed by Donald Trump and his circle, are set to intensify their own antipathy to the US. At the same time, many also applaud what is still being called ‘China’s rise’. The connection is not accidental.

China’s leader, Xi Jinping, loves a party – his party.

He’s not going to incoming US president Donald Trump’s inauguration party in Washington on Monday (Tuesday AEDT) despite being invited. Why travel so far to stand at the edge of someone else’s limelight?

Xi does, however, see the world’s fascination with – and in places distaste for – Trump as offering the Chinese Communist Party a further opportunity to seize economic, ideological and possibly also territorial ground in what he views as an epic global battle with the US.

Australian opinion leaders, many of them distressed by Trump and his circle, are set to intensify their own antipathy to the US.

At the same time, many also applaud what is still being called “China’s rise” despite its growing economic and demographic troubles. The connection is not accidental. The People’s Republic of China perceives itself as the new centre of global values, displacing the US and thus, it anticipates, the rest of the West as the latter’s commitment to democracy, freedoms and openness is overtaken by other priorities. This is a narrative that has spooled out steadily across recent decades.

Although the US supplanting of what was then still imperial Britain as Australia’s core protector was largely welcomed after World War II, a chill was cast on the US-Australia relationship when the Menzies government introduced conscription in 1964 and the country became more deeply enmeshed in the Vietnam War.

Across the following years, for most Australians, the US has recovered its place in our affections as the irreplaceable security ally and natural partner on many other fronts.

But for others, including among elites such as at universities and in left politics beyond the Labor core, which remains largely supportive, the US has defaulted post-Vietnam into the prime target of their hostility, despite its cultural lures such as music, streaming and movies.

During these same decades, the PRC has emerged as a society that has attracted and sustained respect bordering on admiration, building on the popularity among some Australian elites of CCP chairman Mao Zedong and his Red Guard cult, despite Mao’s responsibility for the deadliest disaster of the 20th century, the Great Leap Forward.

Changed intellectual and institutional settings have helped foster this trend of PRC good, USA bad.

This shift reflects the success of prime Beijing diplomatic goals – to prise Australia from its long closeness to the US and to wedge Australian political parties so they begin to compete for Chinese approval, having been reminded cleverly of the claimed voting priorities of Chinese Australians.

The study of international relations has become overlaid widely in Western academe by critical theory. This concept broadly originates from German thinkers Immanuel Kant (18th century) and Karl Marx (19th), who helped extend Enlightenment views of the universal application of the sciences to human arrangements too, but pushing beyond mere analysis to critiquing societies and international arrangements viewed as repressive and resisting universal principles seen as just.

In the 20th century, Italian Antonio Gramsci and Jurgen Habermas, another German, both influenced by Kant and Marx, intensified their predecessors’ critiques of capitalism and liberalism, and of what they saw as hierarchies of power. They challenged the attainability of objective truth and pushed beyond class struggle towards identity struggle emanating from gender, sexuality and race.

This critical theory overlay increasingly has dominated the study of, and thinking about, the world in which the US continues to play an outsized role and therefore to stand out as the principal target for the constant critiques required for recognition and recompense in our academic and other institutional worlds.

By comparison, in Australia the PRC and the CCP that has become under its dynamic general secretary, Xi, the sole truly autonomous institution in the whole vast country are being studied less.

Two universities have abolished their China studies centres in recent years and few others have sustained former international reputations for their work on contemporary China and its governance as a result of administrative and academic reprioritising.

At our universities there are now disturbingly few experts on China’s economy and its military and security sector, or even its hegemonic ruling party. Honourable and impressive exceptions remain, but they are just that.

In comparison, Australia steadily has developed other organisations that have gained international admiration and influence for their pioneering research on contemporary China and on the relevant settings – led by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute alongside the Lowy Institute.

And the Australian American Leadership Dialogue has played a core role in deepening and broadening the connections and mutual understanding between influential Australians and Americans.

Surprisingly, however, support for such institutions from the government – a prominent and in cases decisive funder – is set to become more conditional following a recent review that would require them to reflect Canberra’s own priorities.

The broader setting is a lack of knowledge and – more surprising – even curiosity about the PRC and CCP, despite the unnerving pace of change wrought under Xi.

The challenges posed by Chinese languages; the limited level of regular coverage of China in most of the mass media and the almost total neglect in social media; the cultural gap; the lack of Chinese friends – living in China or here in Australia – among much of our opinion-forming elite; and the mostly modest personal experience of China combine to create a default acceptance of long-held nostrums and perceptions about the country.

But China has changed greatly, especially across the past decade of ubiquitous politicisation.

In comparison, Australian elites – in common with others, especially in Western countries – have developed an almost pathological obsession with Trump, following every inflection in Trumpist rhetoric and online posts.

This juxtaposition has led to a strange whataboutism – a political tool whereby a critique of Xi or the PRC, say, is required to be balanced by a parallel critique of Trump or the US, as if they were two sides of an identical coin.

When someone’s lack of knowledge of or even interest in a subject such as contemporary China is on the verge of being exposed, that person thus may say defensively, flipping the topic: “Well, look what America did in Iraq” or “Black Americans are treated terribly”.

Such look-over-there whataboutists swiftly leap on a critic of Xi’s brutality on human rights, say, or of his comradeship with Russian leader Vladimir Putin to misdirect the discussion, inventing a straw-man argument by stating that this means the critic of the CCP must also love Trump or endorse every US policy.

So, then, many disturbing developments in Xi’s China tend simply to float past the consciousness of many people, or to be countered by unrelated condemnations of troubling events or rude people in the US.

Such disturbing trends in China include the “smelting of the state race”, as La Trobe University professor James Leibold describes the Chinese project to ensure Han-ethnic culture dominates China’s many other cultures; the reduction of women in public life – none in today’s 24-man politburo; the rapid expansion of the nuclear armoury; the subjugation of Hong Kong; the political mercantilism of trade relations such as Australia has suffered in recent years – dubbed “power trade” by German sinologist Andreas Fulda; the creation of fully CCP-curated “internet sovereignty”; the requirement of students from kindergarten through to postgraduates to study intensely Xi Jinping’s Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era; and the emergence of Carl Schmitt, known as “Hitler’s jurist”, as an influential figure in Chinese legal and philosophical studies.

A further convenient whataboutist distraction for those who are discomforted by critiques of the PRC or CCP is to brand them as hawkish. That those responsible for Australia’s security warn of China’s wide-ranging influence-building efforts and military expansion is used as evidence to condemn as unacceptably militarist or hawkish those who are concerned about China’s totalitarian thrust. Because it is the US that is Australia’s prime defence ally, this hawkish taint is made to appear worse in some eyes, surfing that familiar guilt-by-association-with-America wave.

To a degree, the political right and left have swapped international relations sides in Western countries, most obviously in the case of China, with the right more clearly prioritising human rights and values, and the left the realpolitik of trade and interests.

Foreign policy guru Allan Gyngell wrote an important book that hinged off Australia’s anxiety about retaining a powerful ally, Fear of Abandonment: Australia in the World Since 1942. Today, some elite elements in Australia fear abandonment not so much by the US as by China.

Chinese dissident artists, writers and others who have found homes in Australia are especially perplexed by this environment since they often view themselves as naturally people of the left, persecuted by what has become an overbearing corporate party-state.

Artist and cartoonist Badiucao, now based in Melbourne, who has had millions of online followers, is quoted in Nine Entertainment newspapers as saying “many Australians have a casual relationship to Chinese influence. It is real, it is a threat … There is nowhere to escape for me and many other freedom-loving people in this world as long as authoritarian regimes like China’s keep expanding their power. Silence cannot buy safety or freedom.”

Beijing has long sought to control especially the thoughts and views of those – such as Badiucao – it labels “sons and daughters of the yellow emperor”, people of Chinese ethnicity beyond China’s borders. But China has grown far more ambitious under Xi than just seeking to reel in the Chinese diaspora.

Xi has launched global security, development and civilisation initiatives alongside his loans-based Belt and Road Initiative as core tools for remoulding international institutions and downgrading universal values.

The Decoding China Dictionary says “China promotes a state-centric and relativist conception of human rights ‘with Chinese characteristics’ ” as in Xi Thought – effectively displacing the universal human rights pioneered by the UN.

Xi says: “China has found a path of human rights development that meets the trend of the times and suits its national conditions.”

Strangely, given the roots of the criticism of orientalism by leftist cultural critic Edward Said, a tendency has developed among some in the leftist West to accept, if not tolerate, such behaviour, such positions – as if excused by a form of Chinese cultural exceptionalism, by the alleged requirement for harsh measures to rule such a large population, or by the CCP claims of China suffering uniquely “a century of foreign humiliation” – as justification through a partly confected and elevated victimhood.

Six Australian academics, proposing “ideas and concepts to reinvigorate a progressive approach to Australian foreign policy” in a paper in the Australian Journal of International Affairs in 2022, scarcely mention human rights while claiming that using the phrase Indo-Pacific to refer to our region and “elevating the role of former colonial powers in AUKUS” provide “a potent example of the global right in action”.

The article says that in the Pacific “Australia must ensure that its financing is complementary to China’s, rather than displacing it” and that “a progressive realist posture on deterrence would entail signalling that Australia would not be part of a military response” to a Chinese attempt to seize Taiwan, even though success in such a move “would signal the end of US primacy in Asia”. It adds that “a logic of redistribution (of power) requires giving China a bit more space and the US a little less”.

East Asia Forum, a platform based at the Australian National University, editorialised 10 weeks ago that “the threats to democracy in the West emanate primarily from within, not from Beijing or Moscow”.

And former Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade secretary Peter Varghese, now University of Queensland chancellor, has said in a presentation to Asialink, whose council he chairs, that “constructing a stable China-constraining balance does not turn on the retention of US primacy, although it certainly requires the US to be a keystone of that balance”.

Varghese, highly influential, thus introduces two key concepts to this challenging new international relations discourse: that China may be constrained rather than contained and that “however desirable US primacy has been for Australia, it is not a vital Australian interest”.

In 2024 a group of 50 prominent Australians, including former foreign ministers Bob Carr and Gareth Evans, signed a letter urging “a new detente”, saying: “We support a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region in which the US and China respect and recognise each other as equals”, while Australia pursues “activist middle-power diplomacy”.

Washington has already reshaped its alliance networks from a hub-and-spokes arrangement in which it was always central, to a latticework – probably more sustainable and effective today – in which its allies such as Australia, Japan, The Philippines and South Korea also relate more closely between themselves.

But it remains to be determined not only who else, alongside or instead of the US, will step up to champion democracy and freedom more effectively and how, but also how important these values still are to a significant section of Australians and whether they may have been successfully tainted as American or hawkish.

Meanwhile, there is no ambiguity about Chinese party-state values or interests.

Xi says: “Marxism is not to be kept hidden in books. It was created to change the destiny of human history … All mankind needs a new order that surpasses and supplants the balance of power” – thus dismissing the earnest goal – just such balance – of the Australian international relations establishment.

He says: “A new world order is now under construction that will surpass and supplant the Westphalian system” – international society comprising sovereign states.

The PRC is not seeking to export violent revolution but to rewire the global order from inside.

Xi’s party-state ideology and social system are “fundamentally incompatible with the West”, he says.

Thus “our struggle and contest with Western countries is irreconcilable. So it will inevitably be long, complicated, and sometimes very sharp … To us, war as a means to protect our core national interests is not in contradiction with the path of peaceful development.”

China, he says, “is moving closer to the centre of the world stage”, closer to the dynasties-old concept of tianxia (“all under heaven”), by which nations around China conform themselves to its ultimate supremacy, gaining thereby economic and security benefits.

This is described by philosopher Zhao Tingyang, at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, as China’s “whirlpool formula”. A key part of this goal is to shape how the rest of the world thinks about and behaves towards the party-state so that it determines global goals, institutions and trends, and is not defined by them.

A leading expert on the CCP, Jude Blanchette, who holds the Freeman chair in China studies at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, wrote in The Wire China journal that “Xi wants the world to know what he thinks, for he sees global politics as a battle not only of influence and power but also of ideas and narratives”, and China’s rise as a fulfilment of historical destiny.

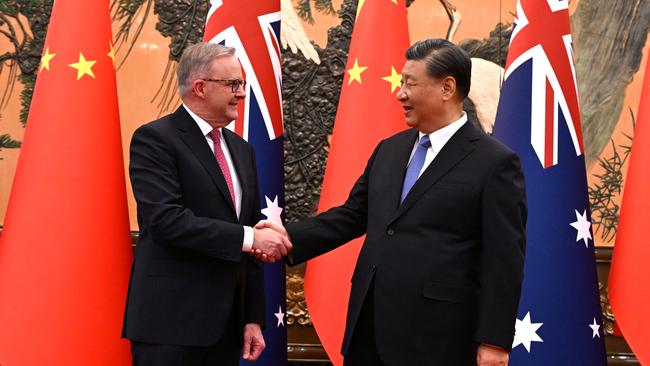

For now, Beijing is claiming to be enlisting Canberra in this enterprise. For instance, Xi lauded, to Anthony Albanese a few weeks ago in Peru, “our collective hard work in the same direction”, while Premier Li Qiang spoke of “ushering in a brighter future of our relations along the right path”.

China Daily editorialised that “Australia might offer some useful reference for those struggling to strike a balance” between China and the US, and celebrated Chinese commentator Hu Xijin wrote warmly of Australia as “the first US ally to make a clear change in its attitude towards China” after Washington branded Beijing its top strategic competitor.

What, then, is Australia’s position in this ideological battleground, which may become even more willing as Trump takes charge?

If the US under Trump chooses to shed or is forced from its expensive but stabilising primacy in our region, will others – Australia? – step up to champion democracy, freedoms and human rights, alongside or instead of the US? If so, what preparations are under way?

Or are those values – inseparable, ultimately, from our interests – to be rebranded as exclusively American or hawkish and thus downgraded to low priority?

In recent times Canberra – and increasingly on a bipartisan basis – has disciplined its political discourse to avoid rhetoric that may antagonise Beijing or that may arouse whataboutist accusations of pro-Trumpism. So public answers to such questions remain elusive or unconvincing.

Surprisingly to some of his old antagonists in both of our main parties, Kevin Rudd – who will be attending Trump’s inauguration as Australia’s ambassador to the US – holds some of the keys to understanding better what we might do.

In his new book, On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World, Rudd says the PRC is launching “the deepest assault on liberal economic theory that the world has seen”, and that the context of its global ambitions include a decline in the appeal of universal human rights, and “democracy in retreat”.

The most striking warning of what failure to uphold such values may look like is portrayed powerfully in the recently completed masterwork of Chinese-Australian artist Jiawei Shen whose story, and that of the painting, are brilliantly captured in the documentary film Welcome to Babel.

His vast four-walled, three-storey high artwork The Tower of Babel chronicles in vivid and striking detail, in places grim and challenging, the turbulent history of communism in the 20th century and its vain efforts to create a utopia, often through cruel tyranny.

Shen’s Cultural Revolution portrait of soldiers in a watchtower over a snow-smothered border, Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland, became an iconic work. Now aged 76 and wiser, he understands especially well that Xi and Trump stand not only in different countries but also in trenchantly different ideological landscapes, although fearing Xi implies nothing for one’s feelings about Trump.

The former will be watching in Beijing an edit of the latter’s inauguration on Tuesday. He will feel he has Trump’s measure. Time will tell.

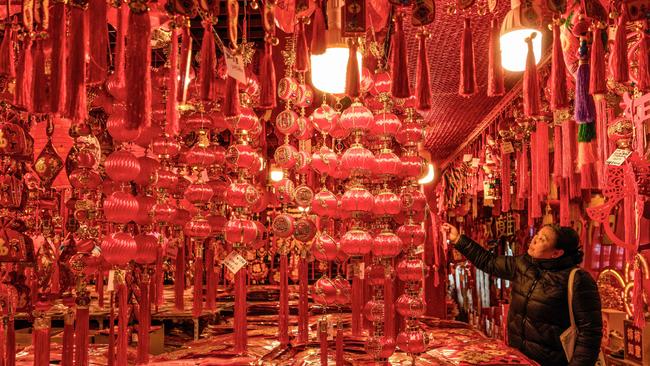

Thus a great deal is at stake for Australia, as Trump triggers an avalanche of elite antagonism, while Xi devoutly presses on towards his epochal goals as the Snake Year – his own Chinese zodiac sign – slithers into sight on January 29.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.