Cut! Life is too short for these bloated epics

We are accustomed to thinking of our culture as chronically distractible, our attention spans nuked by iPhones and TikTok. And yet modern cinema swarms with leviathans.

Martin Scorsese’s last film, The Irishman, was 3hr 29min long. James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water was 3hr 12min. The director’s cut of the Marvel film Justice League goes on for more than four hours. The last James Bond film, No Time to Die, was the longest in the franchise’s history at 2hr 43min.

Cinema is a model of epigrammatic restraint compared with TV. It would take 90 hours to watch all of Mad Men. Succession - much praised for the modesty of its three series - lasts 30 hours and boasts a final episode that is the length of a feature film.

In my role as this newspaper’s podcast critic I am weekly crucified on the altar of human self-indulgence. A new podcast can take a full day to listen to. Joe Rogan, the form’s most successful exponent, regularly records episodes three or four hours long. Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History features five-hour episodes. Even the popular coprological whimsy Who Shat on the Floor at My Wedding? lasts ten hours in total.

What is going on? An important factor is the declining power of gatekeepers: the editors and producers who once guarded the public from the excesses of creative narcissism. A good radio producer would chop Rogan up into neat half hours (and cut the stuff about aliens). But Spotify and YouTube do not employ radio producers.

The effect is most pronounced online, where “creators” access fans directly and feed the ravenous faithful hours of audio via podcasts or thousands of words via Substack newsletters. But even venerable publishing houses are dispensing with the sorts of editors who spent months cutting, pruning and (industry secret) rewriting books. A couple of weeks ago Penguin Random House laid off several of its most famous senior editors - exactly the formidable types capable of restraining garrulous authorial egos.

Instead, the power of the “personal brand” is ascendant. Become famous enough and nobody will be able stop you going on for as long as you want. The Running Grave, JK Rowling’s new book (as Robert Galbraith) is nearly 1,000 pages long. Crossroads, Jonathan Franzen’s last book was 600 pages (and is the first instalment of a promised trilogy). Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light was an 800-page advert for the benefits of a cold-blooded editorial massacre. It is no accident that the most famous directors make the longest films - Nolan, Scorsese, Cameron.

Once, people working in the creative industries used to talk (sometimes over-optimistically) about making art. Today, the buzzword is “content”. There is a difference. Art implies something individual, daring and well-formed. Think of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope or David Lean’s Brief Encounter. Content is the endless, formless stuff pumped into the culture to satisfy commercial demand - the same demented imperative that led to unwieldy Victorian serialised novels which went on acquiring new chapters and improbable plot developments for as long as readers flocked to the relevant magazine.

In the 21st century everything successful must become a franchise. Every commercially reliable author, character, podcaster or director is milked for as many hours or words of content as possible. Familiarity breeds excess.

Underpinning that excess is a yearning to create a cultural “event”. Films, books and new TV shows can easily sink unregarded into the fragmented confusion of modern entertainment. Size is a signal of importance (and easier to achieve than genius). Virtually every other film and novel aspires to be “iconic” or “epic”. For in an age of three-minute TikTok videos and 280-character tweets, length has acquired undue status as a sign of seriousness.

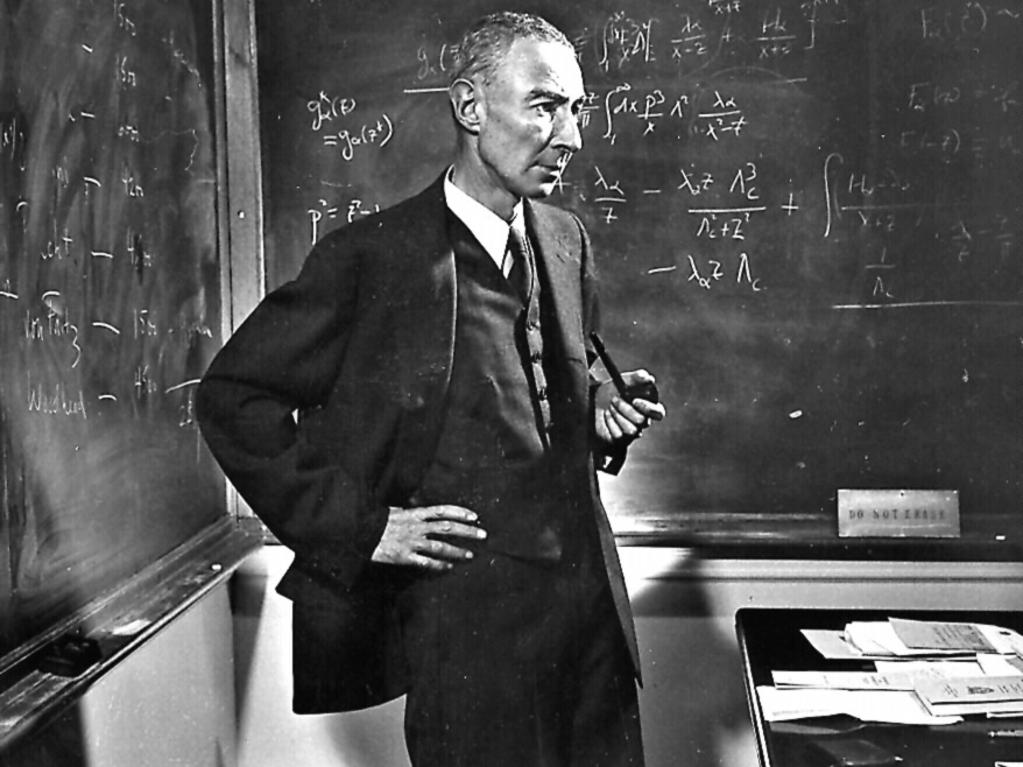

Film critics have been gloating over young audiences sitting through the three hours of Oppenheimer as if art was merely an endurance test. In fact, much overlong modern content is the opposite of a challenge. It’s comfort food. More time revelling in the familiar tics, tropes and preoccupations of Superman or Scorsese or Mantel.

The notion that scale can be substituted for profundity is a recurring mistake in the history of culture. Ask the composers of 19th-century grand opera. Or the painters of the vast, unregarded historical and mythological canvases which millions of tourists will traipse heedlessly past in museums across Europe this summer. It is Vermeer with his modest paintings of light effects of domestic interiors who is responsible for this century’s blockbuster Old Master show.

Who now watches the epics of Cecil B DeMille? Not many. But Brief Encounter (a profoundly sane 1hr 40min) has lasted.

Brevity is so often more profound than garrulousness. Although I suppose I would say that in a 900-word opinion column.

THE TIMES

A three-hour film about a man getting his security pass revoked, with a nuclear explosion halfway through. Ungenerous, I suppose, to Christopher Nolan. But I was not feeling generous as I limped out of Oppenheimer on Sunday evening, my legs stiff, my brain numb and my eyes double-glazed with boredom. I concede that the film has its moments (well, it has a good nuclear explosion). People I respect seem genuinely to have enjoyed it. But would anyone dispute that it could have been shorter?