Coronavirus: How COVID-19 spread through northern Italy

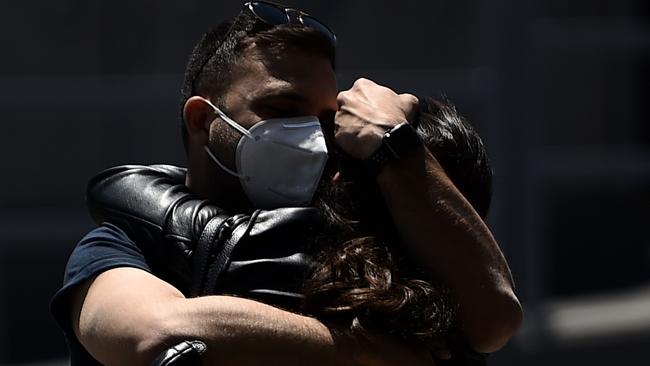

It was already too late for Italy when the first COVID-19 patient was diagnosed. Families were torn apart but a stunned nation can take solace in small acts of heroism

When a doctor in the small northern town of Codogno decided that his patient’s pneumonia was something more serious, Italy’s coronavirus outbreak became official.

Mattia Maestri, dubbed “Patient One”, was a 37-year-old marathon runner whose positive test on February 20 earned him the dubious distinction of being the country’s first confirmed COVID-19 case. When Italy’s first death was reported the following day in Vo’ Euganeo, another small northern town, the government swung into action. Vo’, as it is known in Veneto, and 10 other towns in neighbouring Lombardy, including Codogno, were locked down. All residents were confined to their homes except to shop for food.

But it was too late. It is now clear that COVID-19 had been spreading in northern Italy for weeks. “We think about five people were suffering as far back as mid-January,” says Marcello Tirani, a regional health official.

Maestri was far from being “Patient One”, however. By tracing and testing people in contact with him, then their contacts, the regional authority has estimated that 388 people had already had the virus by the time his infection was diagnosed. Moreover, cases were spread far wider than the 11 locked towns.

The day they were shut down, Camillo Bertocchi, the mayor of Alzano Lombardo in the province of Bergamo, decided with the mayors of neighbouring communities to cancel their carnivals in case they spread the virus. But it was already there.

“By the end of that day we heard of seven cases in our local hospital,” Mr Bertocchi said. Yet the dithering went on. Officials, fearing damage to local industry, failed to put up road blocks. “We were ready,” Bertocchi says. “But then we waited four days for the order to come and it didn’t.”

The quarantined towns ousted the virus. By contrast Alzano Lombardo and Nembro became the centre of Italy’s unfolding trauma.

As their country became the first to go into full lockdown, Italians charmed the world by singing from their balconies. But sufferers were dying alone before being loaded into sacks and buried with a quick prayer by a masked priest. In hospitals and care homes, doctors without protection were dropping like flies. The cull of medics has reached 167 as the total toll rises to 33,601, overtaken only by Britain and the US.

“People were dying so fast — I knew locals who lost a father, mother and brother in the same week,” says Fabrizio Dadone, 58, the commander of the carabinieri paramilitary police in Alzano Lombardo.

Crematoriums were overwhelmed. Dadone and colleagues had to load coffins into army trucks to be taken to crematoriums that had capacity.

“It was a warm, sunny day but dark inside the chapel which was packed with coffins, each one labelled with a name, date of birth and death,” he says. “No one spoke. I realised that in the coffins there were people I knew.”

That day, March 23, the officers loaded 84 coffins. “I’ve worked on murders, suicides and road accidents but to see that number of dead was hard. Not even in a war … ” his voice trembles and he pauses.

“At the time you don’t think but afterwards you can’t help but imagine all those people dying alone.”

Days after the bodies were removed, urns of ashes were returned, which the carabinieri had to deliver to more than a thousand mourning relatives in the province of Bergamo.

The carabinieri were busy. “We dropped off oxygen canisters to the homes of sufferers, then picked them up when the person recovered or died,” says General Antonio de Vita, the force’s commander in the Lombardy region. “We also delivered food parcels. Grandparents would call us and ask us to drop off Easter eggs to their grandchildren.”

Small acts of heroism were required in care homes, where the disease proliferated. Virus patients were sent from hospitals into care homes to free beds. Some homes told staff not to wear masks for fear of scaring residents.

Late on March 17, an ambulance went to a care home in the small town of Villa Bartolomea, in Verona, where 39 of the 70 residents had been killed by COVID-19. Maria Vanzetta, 55, a nurse says: “We entered to find two scared staff with an 86-year-old woman in agony who had trouble breathing, was cold to the touch and had blue legs.

“We knew she was about to die and that she hadn’t seen her family in weeks. I decided to stay with her. It’s tough to talk through the mask and emotionally draining to think you are the last person they will see but I spoke to her and caressed her.”

Days later Vanzetta got a call from the woman’s daughter, Marina Lovato.

“I had to find the nurse,” says Lovato, 59, who works in a day care centre for the elderly. “I realised that she, like me, is called Marina.

“When she told my mother her name that night I hope my mother heard, and was calmer in the belief it was me with her.”

Nurse and bereaved daughter now speak once a week.

Italy may officially have lost more than 33,000 people to coronavirus but a comparison between total deaths in March and April and the number in previous years suggests the real figure may be about 19,000 higher.

Italy was meant to see the impact of its March 10 lockdown after two weeks but the contagion curve failed to dip. Sufferers were giving it to their families at home.

Many companies defined themselves as “essential industries” and continued to work. Mobile phone tracking in Lombardy found 40 per cent of people still on the go.

The country began to reopen on May 18 after warnings that its GDP would contract by 10 per cent this year. Yet when shops and restaurants reopened in Rome, customers failed to show. Some are shutting again.

Thousands of furloughed staff failed to see any promised state payments thanks to the sluggish bureaucracy. Author Beppe Severgnini says Italy could either rediscover the energy that helped it to rise from the ruins of the World War II or sink into a bitter downturn that would strengthen populists such as Matteo Salvini.

“Italy is at a crossroads,” Severgnini says. “During lockdown I was impressed. There was no armed protest, no attacks on 5G towers. Every Italian decided it made sense. It was the sum of 60 million decisions. But now my son, who runs a restaurant, has six employees who waited for furlough payments.

“Italy is good at emergencies and challenges and we will come up with creative solutions. But if disillusion kicks in, Salvini will have a ball.”

There have been glimpses of that creativity. Veneto president Luca Zaia ignored the experts to insist that the 3300 inhabitants of Vo’ would all be swabbed. The tests revealed dozens of positives, half of whom were asymptomatic. All were ordered to self-isolate. “We avoided a slaughter,” he says.

Mass testing and isolation of sufferers was introduced across the region. Veneto avoided the mass contagion of neighbouring Lombardy, where testing was slow to start.

Growing up near Venice shaped Zaia’s determination to halt the virus. “Quarantine was born in Venice,” he says. “It’s part of our identity — back when ships arrived and no one got off for 40 days, not even cats. I’d already thought of quarantining Chinese kids coming back from the new year in China — and was massacred for suggesting it.”

Vo’ continues to lead the way. Andrea Crisanti, a virologist at Imperial College on secondment to the University of Padua, tested all Vo’s residents twice more, then took blood samples. “Nowhere in the world is there such a well-studied group,” he says. “We know who got infected and what symptoms they had and with blood testing we can compare that with the antibodies they produce.”

Next comes DNA testing of every Vo’ resident to see if there is a genetic reason for who gets the virus and who gets it badly.

“We know women are more resistant to TB and some people have protection against HIV,” he says. “Let’s see if we can predict who is at risk with coronavirus.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout