Ukraine’s fierce convict soldiers are most wanted on frontline

More than a fifth of the prison population of Ukraine is serving in the armed forces as the country deals with a shortage of manpower on the eastern front.

Ukrainian convicts have become so highly regarded on the frontline that recruiting officers now visit prisons daily to enlist men and women for assault units fighting Russians on the eastern front.

More than 8600 prisoners have been released from penal institutions since a law was passed in May last year allowing some categories of convicts, including those charged with murder, to have their sentences ended in return for active service. In the past five months alone, 3500 convicts have joined the army.

In all, the authorities say more than 21 per cent of the prison population is serving in the armed forces.

“Combat units are especially interested in recruiting convicts,” deputy minister of justice Yevhen Pikalov told The Times in Kyiv. “They see convicts as having high levels of survival ability, and less psychological resistance to killing. The highest demand is in the category of those convicted for murder.

“Dozens of brigades send recruitment officers to visit our correctional facilities weekly. Sometimes two or three units will visit a specific facility in a single day.”

President Volodymyr Zelensky signed the law in response to chronic shortages among frontline units. The legislation does not apply to those convicted of multiple murder, sex offences or high-level corruption cases.

Mr Pikalov said that among the convicts who had joined the armed forces, 6 per cent had been sentenced for homicide, 55 per cent for robbery, theft and fraud; 11 per cent for narcotics offences; 9 per cent for serious assault, and; 6 per cent for causing fatal traffic incidents.

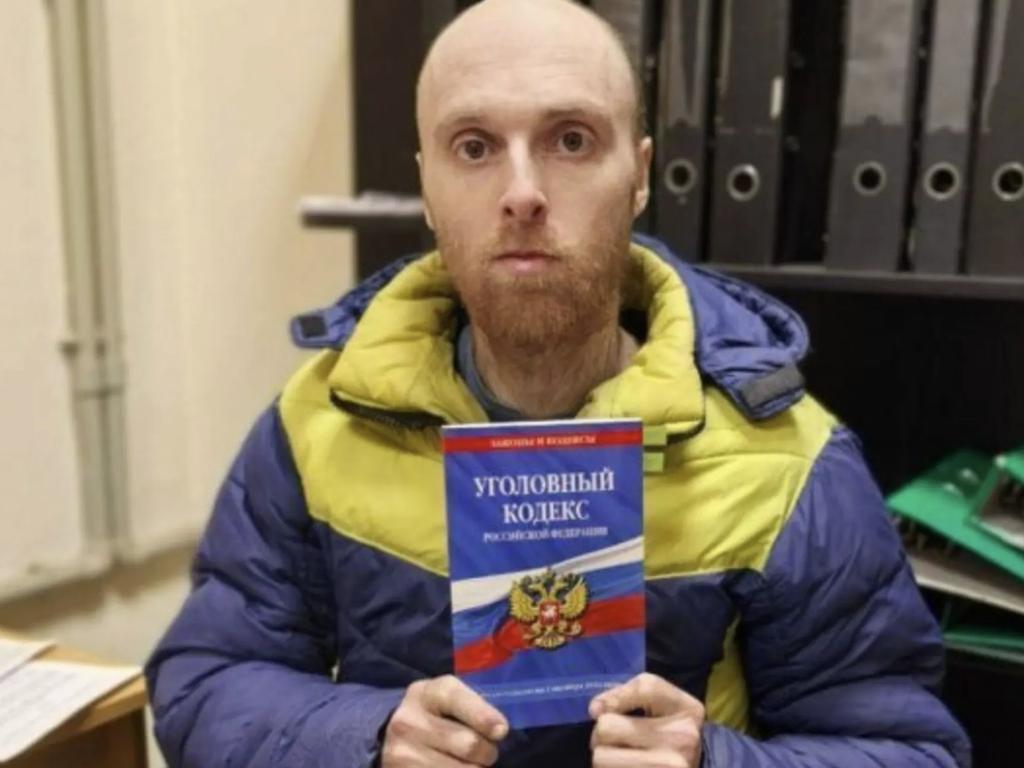

Convicts interviewed by The Times in Ukraine last month expressed a variety of motivations for having joined the army. Most said they had a desire to defend their homeland against Russian invasion. Others said life in the army at least offered a type of freedom not found in prison. Several expressed a sense of redemption they had found through fighting.

Vadym Formaniuk – whose call sign is Makar – had spent 28 years in prisons since he was 15 before becoming a valued member of the 71st Jaeger Brigade, and epitomised this sentiment. “I don’t want my family to remember me for the man I was,” he said. “But who I have become: a soldier serving my country.”

After losing his foot to a mine during a night mission, Formaniuk is attempting to fight a medical discharge and remain a soldier.

The process between a Ukrainian convict expressing an interest in signing up and appearing on the frontline involves several stages. Tuberculosis, HIV and hepatitis C are rife in Ukraine’s prison population, a convict’s medical suitability has to be assessed, and the prosecutor’s office consulted for objections.

Providing the individual is considered healthy enough to fight, and deemed by a military commission psychologically fit for service, the prisoner’s papers are sent to a district court to have his release approved. The convict is then escorted to a training facility.

“The process usually takes between a month or two,” Mr Pikalov added. “But if a unit needs someone specific for a mission, it can only take a week.”

Of the 1300 prisoners declined for service since the program began, 600 were rejected for health reasons, 200 had their applications declined by courts, and 500 changed their minds.

Recruiting officers have also focused on enlisting prisoners from the middle-ranking strata of prison hierarchy known as the Muzhiki. The authorities have learnt that convicts from the prison system’s criminal elite are too resistant to discipline to make good soldiers. The lowest caste, “the untouchables”, are disrespected both in prison and in the army.

Once a convict has joined their unit, their fate depends largely on the attitude of their commander as to how they will be used. Some convicts are grouped together in specific penal units and used for high-risk missions. Others are dispersed among regular sub-units and encouraged to develop their survival skills learnt in prison.

Authorities regard the release program as a success, and have learnt that prisoners volunteering for service often make better soldiers than civilians who have been mobilised into the armed forces.

“It is a good initiative with positive outcomes,” Mr Pikalov said. “We are helping our armed forces increase their numbers, and the social position of prisoners changes once they are seen to be serving their country. Brigades want more convicts to engage with the program. They often prefer working with inmate volunteers over reluctant conscripts.”

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout