A gag will never achieve progress

The left’s new puritans hold convictions that brook no discussion. But without debate, how will warring tribes ever reconcile?

It is a sign of the confusion of the liberal left that even the group of 152 writers who signed a letter to Harper’s magazine in defence of the principle of free expression ended the day unable to agree even on their own letter.

The author and trans activist Jennifer Finney Boylan signed up but then apologised for doing so when it turned out that JK Rowling, a writer accused of transphobia by the trans lobby, was a fellow signatory.

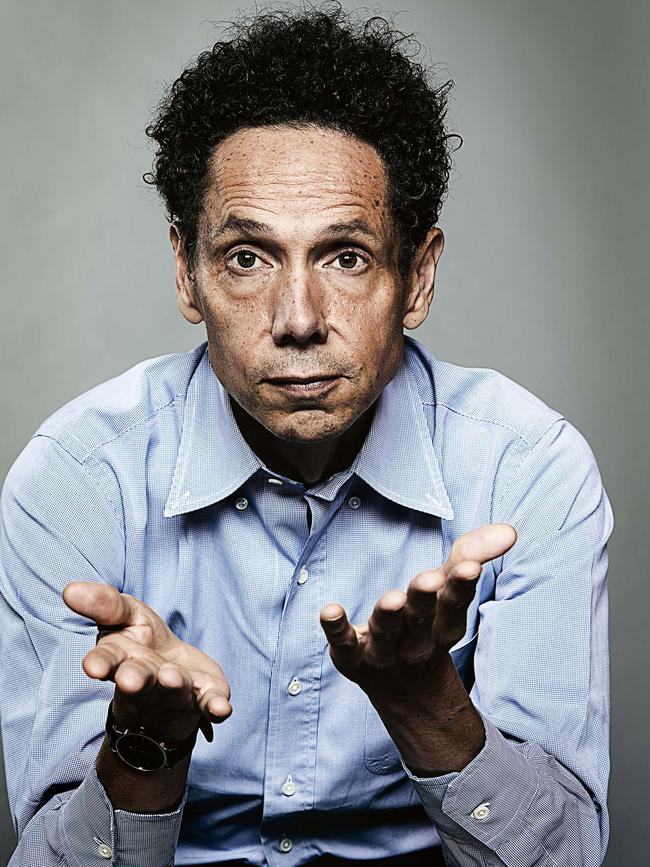

This precious reaction prompted a pithy response from Malcolm Gladwell, another signatory, who said: “I signed the Harper’s letter because there were lots of people who also signed the Harper’s letter whose views I disagreed with. I thought that was the point of the Harper’s letter.”

In that characteristically witty remark, Gladwell encapsulated a conflict, bitter and self-righteous, that is tearing the liberal left apart.

On the face of it the Harper’s letter is, as another signatory, Anne Applebaum, acknowledged, a rather anodyne statement. Who would really disagree with the standard liberal piety that “we need a culture that leaves us room for experimentation, risk-taking, and even mistakes”? Indeed, any letter that manages to bring together Noam Chomsky and David Frum, whose most famous coinage as a speech writer for George W. Bush was “axis of evil”, has to be pretty vague.

For the generation of liberals who came to maturity during and after the progressive conflicts of the 1960s, there is nothing controversial in the letter stating that “the way to defeat bad ideas is by exposure, argument and persuasion, not by trying to silence them”. Yet this is now precisely the point at issue. A new generation that has left the campus and joined the workforce believes progress is achieved by silencing unwelcome voices rather than by defeating them in debate. And for a philosophical debate within liberal culture, it is getting acrimonious.

The consequences are seen every day. In America last month, James Bennet, the opinion editor at The New York Times, had to resign because he chose to publish a piece by a Republican senator calling for US President Donald Trump to use troops to restore order in American cities in the wake of the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota. Rather than disagree with the view and argue back, The New York Times cancelled the employment of the man who commissioned the article.

The actress Halle Berry recently dropped out of playing a trans character after referring, in an interview on Instagram, to a woman transitioning to become a man as “she”. You could taste the fear when Berry apologised, as “a cisgender woman”, for the unintended offence caused (cisgender means a person whose gender identity corresponds to their biological sex at birth). Two years ago, Scarlett Johansson ducked out of the lead role in a biopic about a trans massage parlour operator after also coming under fire. Last week, the psychologist Steven Pinker was the subject of an open letter asking him to stand down from his various posts on account of a tendentious set of accusations about racial politics.

Even dead men are not immune from these threats. The musical Hamilton faced calls for cancellation on the grounds that the show depicts Alexander Hamilton, one of America’s founding fathers, favourably, when he had, in truth, married into a slave-owning family. Writers, musicals and statues are all in the line of fire if they do not embody the sanctioned thought. The brilliant Killing Eve actress Jodie Comer is currently receiving all sorts of stick for dating an American man who votes Republican.

The change in culture has been in gestation a long while. In 2018, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt published The Coddling of the American Mind, which traced the origin and development of this shift back to excessively protective parenting. There is a crooked line, they argue, between banning peanut butter from the school canteen and a language purified of offensive ideas.

Lukianoff and Haidt describe how the liberal ideal of free expression was gradually trumped by the desire for correct utterance in a safe space. As the range of phrases deemed to be harmful grew, so did a desire to eradicate the offending vocabulary from public life.

In a pseudonymous article for Vox magazine, one academic declared: “I’m a liberal professor, and my liberal students terrify me.”

New infringements were identified, such as micro-aggressions — word choices or actions that connote or encode hidden violence. Students began to demand a “trigger warning” before being exposed to texts that might recall a previous trauma. The claim that a text triggered an undesirable emotional response became enough, in itself, to castigate the author. The emotional response took the place of any literary standard for evaluating the text. There were calls at Columbia University for Ovid’s Metamorphoses to come with a trigger warning, since it might prompt students to relive sexual assaults, while an undergraduate at Rutgers University suggested Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway deserved one, because it might cause those with suicidal inclinations to act on them. I have always been afraid of Virginia Woolf myself, but not that afraid.

This was a culture, wrote Lukianoff and Haidt, in which every negative detail was picked out and magnified; in which excessive offence was sought and taken; in which students assumed their own fragility but trusted their own feelings implicitly; and that divided the world into good people and bad. This is the sensibility on display in the online conversation between liberals of different stamps.

How remarkable it is that, rather than vent their ire at actual sexists and racists, there has been so much vitriol directed at the admirable and kind JK Rowling, a woman of impeccable intellectual generosity whose personal philanthropy is testament to the sincerity of her liberalism. Instead, she becomes the victim of the call-out, the desire to cancel that is made so immediate and so easy in the rapid world of online shaming.

This sensibility, which at its most extreme leads to the desire to stop children reading Harry Potter, is usually disparaged as “woke”. But there can be no reconciliation within the liberal left without a little mutual understanding. Woke has been around since at least as early as 1943, when an official from the United Mine Workers, quoted in an article in The Atlantic, used it as a metaphor for the pursuit of justice: “Waking up is a damn sight harder than going to sleep, but we’ll stay woke up longer.” When, in 1962, The New York Times published an article of “phrases and words you might hear today in Harlem”, the African-American novelist William Melvin Kelley wrote an accompanying piece entitled “If you’re woke, you dig it”. Barry Beckham’s 1972 play Garvey Lives! gave a character the lines: “I been sleeping all my life. And now that Mr Garvey done woke me up, I’m gon’ stay woke. And I’m gon’ help him wake up other black folk.”

Woke, in other words, has impeccable origins in the desire for equality between people of all backgrounds. A desire shared, no doubt, by every one of the 152 signatories to the Harper’s letter, and not just the leading black intellectuals among them, such as the historian Nell Irvin Painter, the poets Reginald Dwayne Betts and Gregory Pardlo, and the academic John McWhorter. Though the cancel culture has tipped into aggressive and at times preposterous illiberalism, the response cannot be to seek to cancel it. Far better to try to understand it.

It is an axiom of cultural argument that, in any dispute, it is worth considering whether both sides might not be right. The subtitle of The Coddling of the American Mind is instructive: “How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure.” And the conflict really is the clash of competing good intentions. Racial epithets that were once in common use on television cannot now be used, and this is progress. If it is now illegal to discriminate against people on the grounds of irrelevant criteria of personal origin or gender, then this is progress too. Our language and the ideas we use it to express should be invigilated, and vicious discourse stamped upon. The question that divides the two sides in the liberal fight is how.

The historian Henry Maine once said that the whole of human history could be summarised in the move from status to contract. Power that was once inherited and assumed has slowly been tamed and distributed more equally. This is the bedrock of the argument that we are living through. The standard liberal response to debate is that it should be essentially self-policing. “He who knows only his own side knows little of that,” as John Stuart Mill wrote in On Liberty, a book-length treatment of the dangers of the cancel culture. The truth, he argued, will emerge out of a series of spontaneous encounters, and this is the only argument that can hope to reconcile the warring liberal tribes. Let us talk and the truth will out.

People in public life do enjoy power and status, but the way that gets called out is by letting them speak and allowing their foolishness to become plain. Or as that other star of musical theatre, Thomas Jefferson, put it, when he inaugurated Virginia University: “This institution will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.”

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout