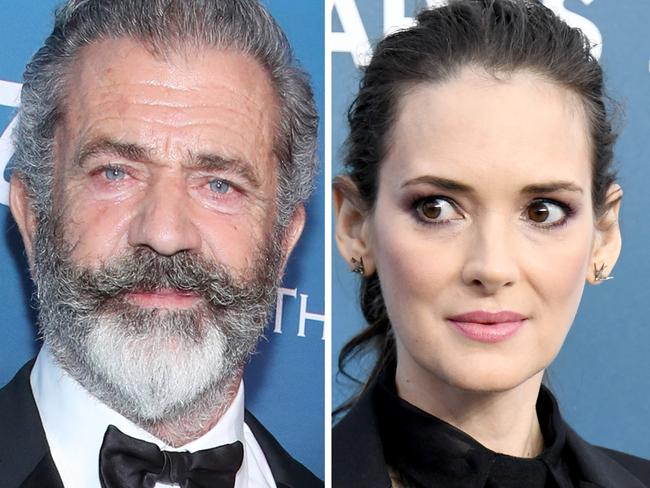

Mel Gibson’s mouth lands him trouble again as Winona Ryder speaks out

He’s our greatest acting export since Errol Flynn ... but when Mel Gibson stuffs up, he doesn’t do it by halves.

Mel Gibson, actor and director extraordinaire, is in the news again and not looking good.

Why? Because Winona Ryder in an interview with London’s The Sunday Times last month repeated the claim she made in 2010 that the star of the Lethal Weapon films and the director of Braveheart had been anti-Semitic to her in an especially repellent way. “Why you’re not an oven dodger, are you?” she says he asked her, a flip reference to the Holocaust. Ryder claims he also said to a gay friend of hers, “Oh, wait, am I gonna get AIDS?”

A representative of Gibson has said the allegations are “100 per cent untrue’’ but Netflix has dropped him from the sequel to Chicken Run, the animation feature in which he first voiced the role of Rocky the Rooster back in 2000.

It is, alas, true that the most famous actor to make his name in Australia since Errol Flynn does have form in both these areas.

In 2006 Gibson was pulled up for drunk driving and he said to the arresting officer: “My life is over. I’m f..ked. Robyn’s going to leave me” — referring to his first, Australian, wife who bore seven children to him. And then, “F..king Jews … the Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world. Are you a Jew?” Later, though, in an interview with respected American broadcast journalist Diane Sawyer he apologised for what he called his “despicable” behaviour, “blurted out in a moment of insanity”, and said he wanted Jewish leaders to help him “discern the appropriate path for healing”.

He’s a weird and wonderful customer, but we shouldn’t let the weirdness dispel our sense of the wonder. After Gibson broke off with the woman with whom he seemed to have a marriage made in heaven he took up with Russian pianist Oksana Grigorieva. He talked in a rage about her, how if she were “raped by a pack of n.....s” it would be her own fault.

When Gibson stuffs up, he doesn’t do it by halves; he seems to open his mouth and say the worst thing in the world to contemporary liberal sensibility and the awfulness of what comes out goes way beyond the bounds of decency from any point of view.

Yes, but the man who years ago said to an interviewer, pointing to his bottom, “This is just for shitting,” has had an utterly remarkable career in artistic terms all — or almost all — controversy aside.

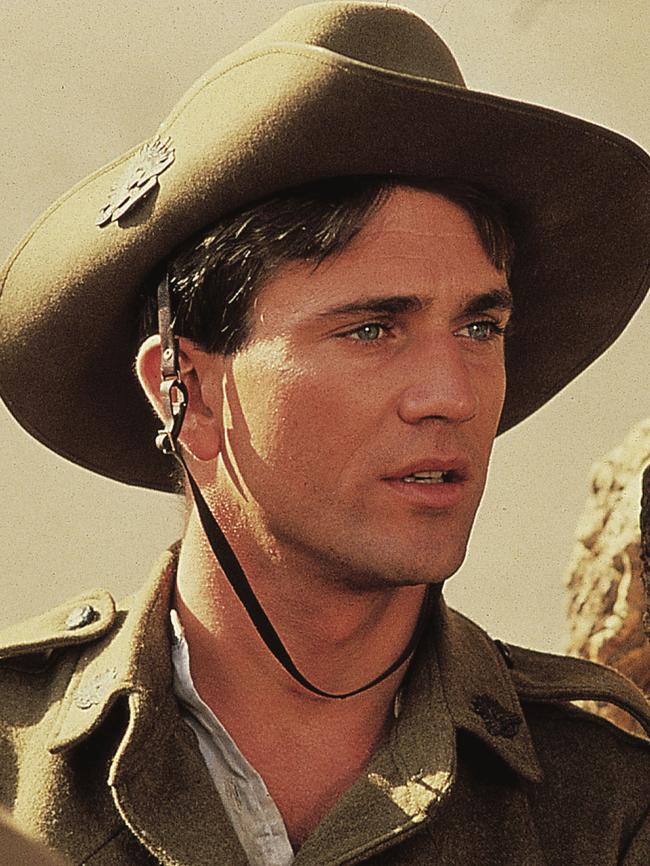

He made those notable Australian films Gallipoli (1981) and The Year of Living Dangerously (1981) — the Indonesian one from the Christopher Koch novel — with Peter Weir, one of the inventors of the reborn Australian cinema and then from far-off Australia he gained the world’s attention with the Mad Max trilogy. American critic Vincent Canby said he didn’t know what star quality was but whatever it was Gibson had it.

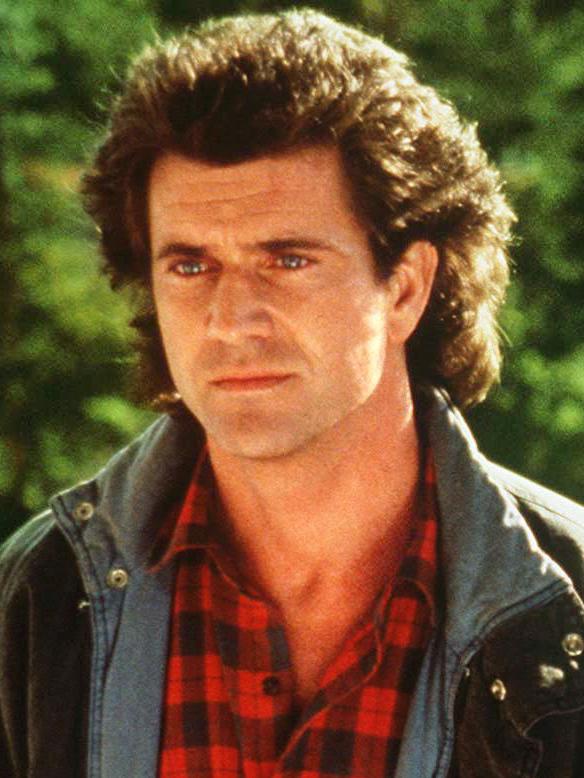

And that quality led pretty directly to the fabulously successful Lethal Weapon films, which made it abundantly clear that Gibson was a leading man in the grandest Hollywood tradition. That the man who played Fletcher Christian to Anthony Hopkins’s Captain Bligh in The Bounty was a star with a mesmerising presence, like Australia’s Flynn in that respect. Yes, but he also had things in common with that other Fletcher Christian, Marlon Brando — a unique and ornery artistic sense of destiny that soared eccentrically where it would.

At the end of his stint at the National Institute of Dramatic Art, in a coupling the world might come to envy, Gibson played Romeo to Judy Davis’s Juliet. He did Death of a Salesman with that great London Jewish actor Warren Mitchell (who went from playing Alf Garnett to becoming an Australian citizen and doing a famous Queensland King Lear with Geoffrey Rush as his Fool).

For all his moments of occasionally shooting off his mouth, Gibson has always been an actor’s actor, a director’s director. In 1996 he set about playing the title role in a film of Hamlet directed by Franco Zeffirelli, with Glenn Close as the Queen, Alan Bates as the King and, as the Ghost, arguably the greatest Shakespearean actor of his generation, Paul Scofield. Gibson’s performance is discernibly in high Australian and has the weird antipodean quality of being almost laconic, a man of action trapped in a box of language. Scofield said of him that he was “not the sort of actor you’d think would make an ideal Hamlet but he had enormous integrity and intelligence”.

Gibson brings to mind the line in the song, “If you’ve lit up the occasional candle, you’re allowed the occasional curse.” Within a few years he had won best director and best film Oscars for Braveheart, in which he also starred.

Whatever you think of this song to medieval Scotland, which ends with the characteristic Gibson touch of a disembowelling, it does everything it sets out to do. He was attacked by gays for the scene in which another distinguished actor, Irish-American Patrick McGoohan, as the tough old Edward I, Longshanks as he was called, hurls his son’s male lover out a window. It has an astonishing brutal power and the gay lobby seemed to be barking up the wrong tree because Edward II’s effeminacy is emphasised as long ago as Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II. Besides, as Gibson says, he wanted to show the old King as a psychopath.

But Gibson has always walked to his own strange drum. Who but he could make The Passion of the Christ and have the dialogue of the Gospels translated back into the Aramaic Jesus presumably spoke, despite the fact the original scriptures are in the form of Greek that was the lingua franca of the Roman Empire. It doesn’t matter because the upshot, which has the visceral violence of all of Gibson’s work, a spectacular transcendence of sadism that takes away the breath, ensures this lunatic endeavour in a reconstructed ancient language is arguably the most concerted attempt to take the foundation myth of our civilisation since Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St Matthew. Apocalypto, too, has that atavistic violence of ritual horror and it too reconstructs an ancient language, that of the Mayans.

But there is also the black magic of language in all Gibson’s work. It’s there in a different way in the Lethal Weapon scripts and the wry way he tilts them.

Is his Jesus film anti-Semitic? No. Does it matter that he grew up, during all those days of being at St Leo’s in Wahroonga, inducted into a form of Catholicism that adheres to Sedevacantist, the belief that post-Vatican II the Catholic Church hasn’t had a true Pope, the chair of St Peter is vacant. Well, it’s not my variety of Catholicism, but it takes all types.

Of course it’s creepy when he says of Broadway critic Frank Rich: “I want to have his intestines on a stick …” (because Rich criticised his father). But Gibson is always in danger of shooting himself in the foot because of the individuality, the eccentricity, of his obsessions. It’s good he could return to directing with Hacksaw Ridge. He’s a man whose dark side turns to gold. The Passion of the Christ is the top-grossing R-rated film of all time and the supposed right-wing fiend has given millions to preserve the Mesoamerican rainforests. At the end of the day Gibson has brought a lot more credit than disgrace to the Australia he once called home.

Scofield may have been right that he wasn’t one of nature’s Hamlets but think of what a Macbeth he might be.

That sense of fated uncontrollable violence, of sanity as the impossible tightrope, a vision of blackness and death, of enemies without and within, and through it all the mystery of marriage. Why don’t we invite the man who has showered NIDA with gold to come back to Sydney and do Shakespeare’s murder and marriage play with his old histrionic sparing partner, Judy Davis? What a lethal weapon of a Macbeth he could make.

Winona Ryder should dine out on someone less prone to volcanic self-murder.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout