Without a Jewish homeland these became a perpetually persecuted people

Without a homeland, their community was at the mercy of monarchs, popes and prime ministers. For the writer, tracing the history of Sephardic Jews in Europe was to walk in the forever-moving footsteps of his forebears.

When Abraham, son of Isaac Israel Ergas, arrived in Tuscany in 1594, Spain, from which the Jews had been expelled in 1492, must have seemed a distant memory, destined, like all memories, to eventually fade away. Yet centuries later, my grandmother would talk about Sepharad, the Hebrew name for the Iberian Peninsula, as though time could not dim the sweetness of its blossoms’ wafting scent, the beauty of its sun-lit mornings, the stillness of its star-filled nights.

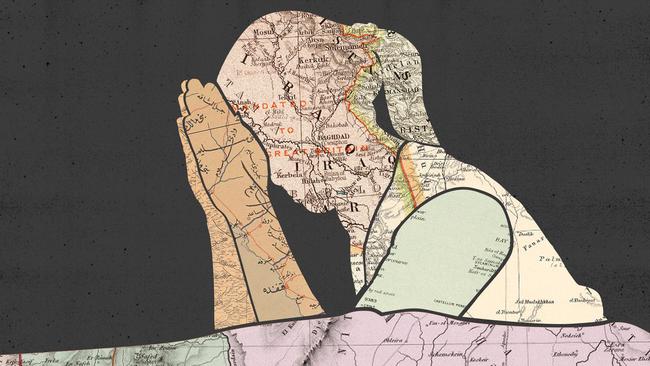

Sepharad was a land she had never seen and would never see. But it wasn’t a place in space, the sort of place one could visit, or to which one could return; it was a place in time. Marked on no map, it existed only in the collective consciousness of what had once been a people. But it was as real as real could be, because it was always there, an inexhaustible, inextinguishable heritage transmitted from generation to generation. And most of all, it was where our journey, with all its blessings and all its pains, had begun.

OCTOBER 7: A YEAR ON

Australia is not the same country — but too many are in denial

Since the October 7 attacks, Australian values have been traduced. What is happening affects the entire country and the collective impact is profound.

After ‘51 days of hell’, former hostage haunted by fear for husband

Aviva Siegel longs for Keith, her beloved husband of 43 years, left behind by a deal that was struck to set her free. Her heart remains in Gaza: in a filthy room, with a weakened Keith, somewhere in the territory’s miserable ruins.

Attacks on Jews at record levels

Australia’s Jewish community has suffered its most traumatic year since records were first kept, with more than 1800 anti-Semitic incidents reported across the country, a staggering 324 per cent increase on the previous year.

No longer ‘one and free’: Nation torn apart by vile ignorance

Not since the Vietnam war, more than half a century ago, has a foreign conflict so divided the nation.

Australia has been weak when we needed to be strong

Labor’s doublespeak and equivocation have made the nation less safe as a result.

‘Genocide’ the modern-day blood libel to demonise Jews

The anniversary of the October 7 massacres compels me to reflect on the toughest 12 months of my long, happy and deeply fulfilling life as a Jewish Australian.

Two enemies, two paths – and one deadly objective

Iran relies on violence to achieve its goal of destroying Israel and its people, while the Palestinian threat is more subtle.

The tweet that captures the cowardice of Labor

There is deep sorrow still on this anniversary of October 7 among Jews of the left like me, deep sorrow and pain. And there is a sense of betrayal.

‘They’re here’: a family’s tale of escape as Hamas terrorists attacked

The October 7 terrorist attacks in Israel shocked the world. In this gripping first-hand account, Amir Tibon describes how his family’s safety hung in the balance for hours.

The nagging thought haunting the families of the Hamas hostages

A year on from the October 7 attacks, with more than 60 hostages still in captivity inside Gaza, families are stuck in a world of questions without answers.

Look around, and you’ll see Hamas’ goals of October 7 fulfilled

Israel is fighting on every front, anti-Israel protests are global, diplomatic pressure on Israel is building and its allies are losing patience. Division and mistrust between Muslim, Jewish and other populations are growing around the world. There is only one way to turn it around.

The real-life horror movie our politicians refuse to see

Raw footage, running for about 45 minutes, captures the unspeakable horror of October 7: innocent people being murdered, beheaded, hunted down, raped, kicked, bashed, burnt alive. Here’s what Australia’s leaders had to say when I asked if they had seen it.

We need to talk about the crisis in Western civilisation

The October 7 pogrom unleashed a wave of sympathy across the West – for the perpetrators.

To the political left, some kids matter more than others

In my life I never imagined a situation where the government of a free, functioning democracy such as Australia would be unable to tell right from wrong. Would be so comfortable walking in step with the wicked, unable to take a stand against evil.

Notes from a long war: Israel one year on from the October 7 massacre

This war on the ‘villa in the jungle’ was launched to test a thesis. It has been disproven at a very high cost.

In exile: how Jews became a perpetually persecuted people

Without a homeland, their community was at the mercy of monarchs, popes and prime ministers. For the writer, tracing the history of Sephardic Jews in Europe was to walk in the forever-moving footsteps of his forebears.

So it must have been for Abraham Ergas, too. Spain’s expulsion of the Jews, who had been in Iberia since at least the 3rd century AD, had been brutal. Machiavelli was hardly soft-hearted, but even he denounced Ferdinand of Aragon’s decision to expel the Jews as an act of “miserable cruelty”, which relied on “the excuse of religion” to despoil innocent victims. The Jews, having refused to convert to Christianity, were given virtually no time in which to liquidate their possessions. Stripped of their belongings, prohibited from taking with them coins, jewels or precious metals, they were left desperate and destitute.

Historians still argue as to the expulsion’s causes. Contrary to widely held myths, Spain’s Christian kingdoms had been seen by Jews as a place of salvation, a refuge from the massacres that marked the final centuries of Islamic rule in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula. As Jews fled the Almohad caliphate, Abraham ibn Daud (1110-1180), a great pioneer of Jewish philosophy, hailed the generosity of Alphonse VII of Castille (1155-1214) who had “freed the enchained, fed the hungry, sheltered the weak and the weary”.

But there were few signs of that generosity in the summer of 1391, when Christian mobs attacked Jewish communities throughout Castile and the Crown of Aragon, killing hundreds and forcibly baptising thousands. Even then, the change was not uniform: in Valencia, for example, the middle decades of the 1400s were a Jewish golden age. But the completion in 1492 of the “Reconquista” – the wrenching back of Spain from the Moors – heralded a sharp inward turn, in which the newly consolidated kingdom sought to unify its disparate peoples by eliminating its historic religious diversity.

Hence the ultimatum: convert or leave. Some of the wealthiest Jews accepted baptism, with many becoming “conversos” – that is, Christians who practised Judaism in secret, living permanently in fear of being denounced to the Inquisition. But around 100,000 Spanish Jews would not renounce the faith of their ancestors, preferring death or exile.

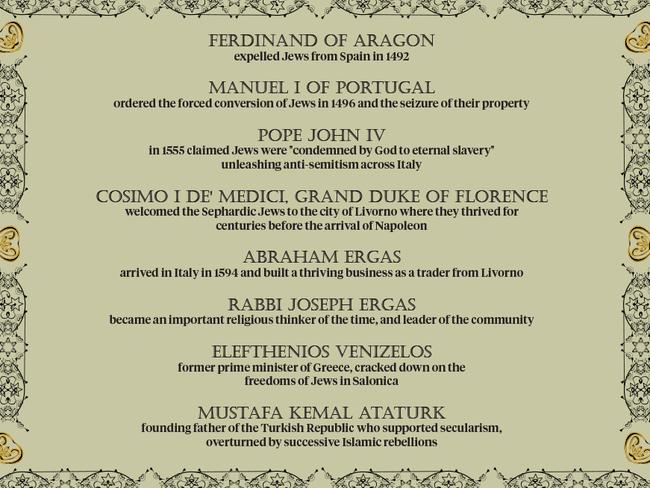

FIGURES OF INFLUENCE:

Lacking the funds needed to travel, the vast majority sought refuge in nearby Portugal. Unfortunately, that proved a fleeting haven: in 1496, King Manuel I ordered the forced conversion of all Jews and the seizure of their property. As converts, the exiles were now fully subject to the Inquisition – and within a few decades, the auto-da-fés, in which alleged “Judaizers” were burned alive, were blazing. Desperately seeking to flee, the exiles crowded into vessels that were always at risk of capsizing or, worse, being captured by pirates, who butchered their victims or sold them into slavery.

Yet the departing “Sephardim” – that is, Jews of Iberian origin – did not leave empty-handed. They brought with them a set of common languages they would never relinquish. Along with liturgical Hebrew, there was Castilian, that evolved over time into a richly poetic language known as Judeo-Spanish, as well as a written language, used mainly for religious and scholarly purposes, called Ladino.

Every bit as important, they had, in their Iberian centuries, forged a unique, strongly held and enduring model of appropriate behaviour – that is, of the character to which one should aspire – that combined piety with commercial flair, prodigious erudition and unstinting statesmanship on behalf of the community.

Those assets would prove vital when 15,000 Sephardim finally reached Italy’s shores. Their timing could scarcely have been less propitious. Sicily, then under Spanish rule, had expelled its Jews in 1492; Naples and Calabria followed in 1510. Shortly after that, papal attitudes towards Jews hardened, culminating in Paul IV’s 1555 bull Cum Nimis Absurdum, which claimed that the Jews had been “condemned by God to eternal slavery”.

The consequences were appalling. In almost every part of Italy violence against Jews, including the kidnapping and forced conversion of Jewish children, was accompanied by measures that herded Jews into ghettos, required them to wear distinctive clothing, drastically limited their range of occupations and subjected them to incessant persecution.

There were, nonetheless, exceptions. Convinced that a Jewish presence would enrich his small state, Ercole I d’Este (1431-1505), Duke of Modena and Ferrara, wrote to the Iberian Jews stuck in the port of Genova, telling them that “We would be very happy if they and their families came here to live.” But nowhere was as welcoming to the exiles as Livorno (or, as it is known in English, Leghorn).

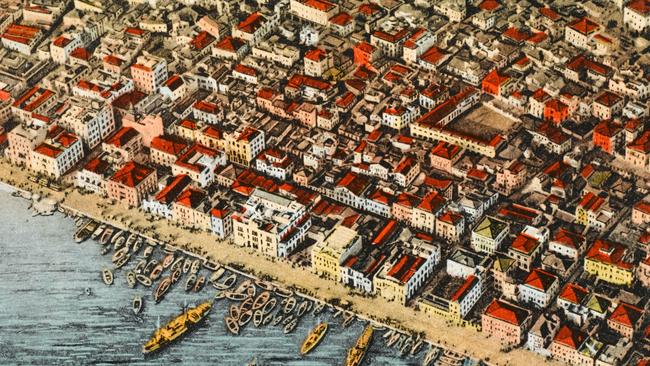

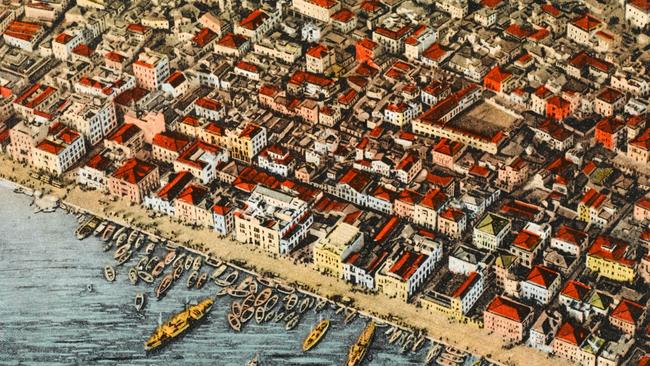

It was originally a fishermen’s village, but Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519-1574), Grand Duke of Florence, and his successor Francesco I, transformed it into a vast port city, rationally designed along Renaissance principles. The problem was that the city had virtually no inhabitants, much less inhabitants who could put its costly infrastructure to good use. To remedy the shortfall, the Medici rulers issued a series of decrees, referred to as the “livornine”, which bestowed upon those Sephardim who moved to Livorno unparalleled freedoms, privileges and protections, including full citizenship and sweeping powers of self-government. The results of the livornine, which remained in place for centuries, did not take long to materialise. As Francesca Trivellato, from Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, shows in her path-breaking economic history of the city’s Jewish community, Livorno’s Jewish population rose from a mere 134 Jews in 1601 to 2400 at the end of that century, before nearly doubling again. With Jews accounting for slightly more than 10 per cent of its population, Livorno became the second largest Sephardic city in the West, surpassed only by Amsterdam.

Settling into that environment, Abraham Ergas quickly made his mark. By 1600, he was on the board of lay officials in nearby Pisa that governed the Jewish community. Once he became a standing member of the board, he brought a slew of relatives to the Tuscan port, laying the foundations of a dynasty. Even more important, the extended family, which remained closely connected with the increasingly far-flung Sephardic diaspora, built a thriving business that – in Trivellato’s words – imported “grain from the Aegean Islands, wax and dates from northern Africa, and colonial goods such as muslins, pepper, and tobacco”.

At a time when it could take years for commercial correspondence to reach its destination, the Ergases sought and relied on an ever broader range of trusted agents. As early as the 1620s, they were active in Istanbul, before expanding to Tunis. Establishing a base in Aleppo, the family’s network stretched to Goa, where their Hindu agents exchanged Liguria’s coveted coral, whose price increased fourfold over the course of the 17th century, for the East’s diamonds and spices.

The risks were enormous; so too could be the losses. “With regard to your request for early information,” wrote the partnership of Ergas and Silvera to Carlo Niccolo Zignago in Genoa, “we will say, as you know well, that those who trade from one distant place to the other never know what might happen.”

But Livorno’s laws made the mishaps easier to absorb and overcome. Investing heavily in the Bank of England, the Ergases became substantial enough to have votes in the election of its governor and deputy governor. With a coat of arms that boasted a lion rampant, bearing a crown, they formed part of an affluent, but still strictly observant, commercial class.

Proud as the community was of its prosperity, it placed an enormous premium on learning. “Get wisdom, get understanding: Forsake her not and she shall preserve thee,” said Proverbs; and the road to wisdom lay in Torah.

That road was, however, fraught with difficulties, compounded by the longstanding belief that some types of knowledge, and especially the kabbalah, had to remain esoteric. Rabbi Joseph ben Emanuel Ergas adamantly rejected that belief. Instead, his Shomer Emunim HaKadmon (Keeper of the Ancient Faith), which is still used in Orthodox instruction, sought to explain esoteric truths to a broader public, deploying Aristotelian methods of rational analysis. With ready access to printing, little censorship and high levels of male literacy, the resulting controversy helped advance the debate from Rabbi Ergas’s Aristotelianism to the newer interpretative approaches that emerged in the second half of the 18th century.

By then, however, Livorno’s sun was setting. Devastating natural disasters, wars in Europe and on the fringes of the Middle East, the mounting power of Britain and a shift in the entrepot business to Marseilles, all combined to marginalise the Tuscan port. After Napoleon annexed Tuscany to his empire in 1808, a half-century of stagnation gave way to decline.

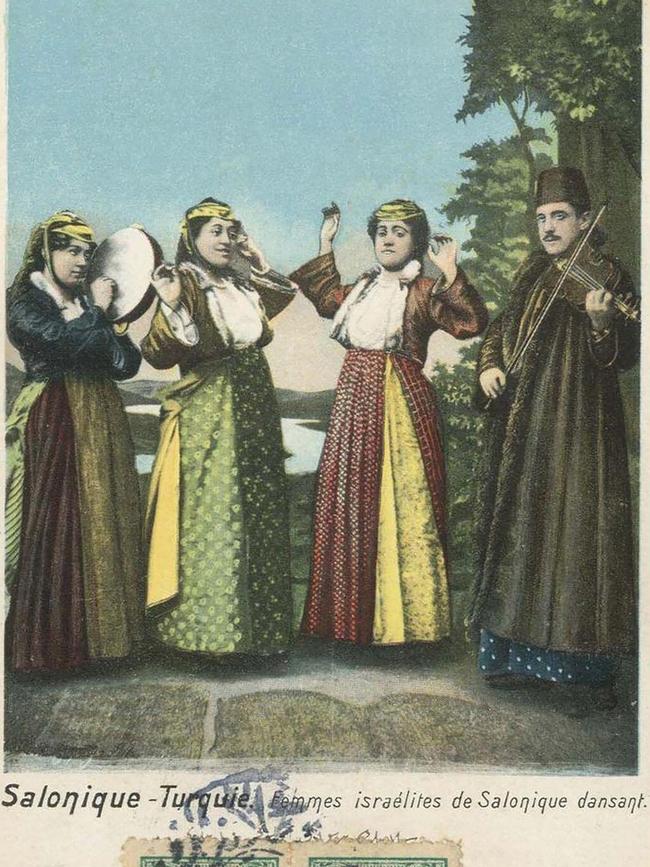

It was, as a result, once again time to move, albeit by choice rather than compulsion. The primary destination was Salonica, which, like Livorno, was a port city with a longstanding Sephardic presence. In the 1450s, Sultan Mehmed II had forced the Ottoman Empire’s Greek-speaking (“Romaniot”) Jews to resettle in Istanbul, dramatically reducing the city’s population. It therefore took very little time for the Sephardim, who began to arrive in the late 1590s, to outnumber the other ethnic groups. Already by 1613, they accounted for 68 per cent of the inhabitants, making Judeo-Spanish Salonica’s lingua franca.

Ottoman rule was generally permissive. In North Africa, “dhimmitude” – a humiliating complex of Islamic rules which kept Jews and Christians in strictly subordinate positions – was applied with severity. In Salonica at least, those restrictions had little sway. There had been dark moments, including the decrees of Sultan Bavezid II (1447-1512) that required all Jews to become Muslims. But they were short-lived, revoked for fear of rebellions or of economic collapse.

It was, however, only in the 19th century that the city truly came into its own. The arrival of the Livornese, including a branch of the Ergases, injected a more secular, West European culture, along with a renewed commercial orientation. At the same time, great reforming sultans were seeking to modernise the Ottoman Empire, not least by dismantling barriers to trade. Consolidating a liberalising course that had been set in 1826, the 1838 Anglo-Turkish Commercial Convention eliminated all local monopolies and slashed tariffs.

After similar treaties were signed with other European countries, the volume of Ottoman trade exploded, increasing sixfold from 1840 to 1873. Meanwhile, the empire’s terms of trade (the ratio of the price of its exports to the price of its imports) had nearly trebled, enriching exporters while fuelling a massive surge in imports of manufactured goods. Salonica, with its import/export businesses, freight agents, insurance brokers and shippers took on the allure of a boom city.

But it was also a city of contention. A thriving press, mainly written in Judeo-Spanish, broadcast points of view that stretched from complacent conservatism to ardent leftism. The city’s Socialist Federation, the most important socialist party in the Empire, published incendiary broadsheets and organised massive demonstrations at which its founder, Avram Benarova, addressed crowds of up to 20,000 Salonica workers in Judeo-Spanish, confident that Salonicans of all ethnicities would understand him. Visiting the city in 1911, Labour Zionist (and founding Israeli prime minister) David Ben-Gurion proclaimed it “a Jewish labour city, the only one in the world”.

Yet far from being revolutionaries, Salonica’s Jews were intensely loyal to the Ottoman Empire. The 16th century Hebrew prayer for the government, the Noten teshua lamelakhim (“He who gives salvation to the kings,” Psalm 144:10), which in most other Jewish communities was discarded in the 19th century, continued to be recited in synagogues. Even when Sultan Abdul Hamid II suspended the recently enacted constitution and increased the emphasis on the Empire’s Islamic character, Jewish leaders responded by multiplying the proofs of allegiance. And both the Zionists and the radical reformers saw the future as lying in a modernised, federalised empire, not in its dissolution.

In reality, however, the empire was in inexorable decline. Buckling under the furies of ethnic nationalism in the Balkans and of Russian expansionism, crippled by a persistent fiscal crisis and by a legacy of low literacy that impeded modernisation, the empire’s calamitous defeat in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 presaged its impending collapse.

That defeat’s consequences for Salonica were devastating. The city, which had prospered under the Ottomans, became part of Greece, placing a frontier between Salonica’s merchants and the trading routes in and through the empire that had been their lifeblood. Cut off from its traditional networks, a prominent business leader warned, “Salonica would become a head severed from its dismembered body”.

But the threats were not merely commercial. There was, in effect, a long history of Greek hostility to Jews. Even greater emphasis had been placed on Orthodox Christianity in Greek nationalism than on Islam in late Ottomanism: in 1822, the first constitution of independent Greece proclaimed that “those indigenous inhabitants of the state of Greece who believe in Christ are Greeks”, thus excluding Jews. Antisemitic riots had occurred during and immediately after the Greek War of Independence; despite efforts by the authorities, they periodically recurred, often in conjunction with accusations of ritual murder. When Salonica became Greek, memories were still fresh of pogroms in 1891, which had prompted major relief drives in the city.

There was a further factor too. Until the first decades of the 20th century, Salonica and its surrounding region had been a home to Jews, Greek Orthodox Christians and Muslims, with each group large enough that no other group could prey on it. But the Balkan Wars, the First World War and then the Turkish War of Independence induced a vast “unmixing of peoples” that culminated in the “Convention on the Exchange of Populations” signed by Greece and Turkey on January 30, 1923.

Under the terms of that Convention, Muslims residing in Greece would be forcibly moved to Turkey, while most of Turkey’s Greek Orthodox Christians would be forcibly moved to Greece. In theory, the shifts were a “repatriation”; but as Bernard Lewis, the eminent historian of Turkey, put it, “this was no repatriation at all, but two deportations into exile: of Christian Turks to Greece, and of Muslim Greeks to Turkey”.

The result was an abrupt change in the demographic balance. Greece’s Muslim population shrank from 20 per cent to 6 per cent of the total, making the Jews the most prominent and geographically concentrated minority. Moreover, many of the Orthodox Greeks who had been relocated from Turkey were sent to Salonica, eliminating what had once been the city’s Jewish plurality. In Anatolia, those Greeks had largely been shopkeepers and artisans; now they found their former occupations dominated by Jews. Poorly housed and deported without compensation, they provided fertile ground for a wave of populist antisemitism.

No one did more to fan that populism’s flames than Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936), after whom Athens’s international airport is named. As Greece struggled with mass democracy, Venizelos, a much admired international statesman, was not above using the demonisation of minorities to muster electoral support and deflect public attention from the country’s mounting problems.

Pandering to the antisemitic press, which constantly blamed Greece’s woes on a Jewish conspiracy set out in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Venizelos’s successive governments enacted one discriminatory measure after the other. Salonica’s Jews were placed in a separate electoral constituency, limiting their impact on election outcomes; Sunday was made a compulsory day of rest, despite the fact that in Salonica, businesses had always shut on Saturday; restrictions were imposed on the use of Judeo-Spanish.

It was therefore unsurprising that attacks on Salonica’s Jews became more common, climaxing in a 1931 riot that set fire to large parts of the city’s Jewish district. And it is unsurprising too that around a third of the city’s Jewish population, mostly the better off, emigrated in the first decades of Greek rule – my grandparents, who moved to Istanbul, being among them.

But far, far worse was still to come. On April 9, 1941, Salonica became the first Greek city to be occupied by the Wehrmacht. Elsewhere in Greece, and particularly in Athens, the Nazis’ attempts to deport Jews met with widespread, intense and often highly effective resistance, including from the most senior Orthodox prelates. Not in Salonica.

With the local authorities collaborating eagerly from the outset, all Jewish properties were seized and looted – in theory to rehouse the Christian refugees from Turkey. As it became clear that sweeping deportations were planned, dozens of Jewish families desperately sought to hide. Only five managed to do so, the others being promptly denounced to the occupiers. The Germans consequently had a free hand: between March 15, 1943, and August 10, 1943, 45,200 Jews, including almost all of the remaining Ergases, were packed into sealed freight trains and sent to Auschwitz. Not even five per cent survived – one of the lowest survival rates in Europe.

In the 1930s, there were 56,000 Jews in Salonica. When the war ended, there were 450. The few survivors were lost in a city of ghosts, where their neighbours, who had often benefited from the spoliations, viewed them with fear and resentment. Promises were made, but of the 11,000 premises that had been stolen, only 300 houses and 50 shops were eventually returned to their rightful owners. Other than that, there was no restitution, nor for decades any public recognition of the catastrophe. In any event, the dead were gone and nothing could bring them back. And gone with them was Jewish Salonica, the “Madre de Israel”.

What remained for us was across the Bosporus, in magnificent Istanbul. Led by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk – whom my family worshipped – the recently founded Turkish Republic had embarked in the 1920s on an extraordinarily far-reaching program of secularisation, promising tolerance for all of Turkey’s faiths.

In some respects, the promise was fulfilled. But Ataturk’s sweeping reforms prompted a fierce reaction, with major rebellions, that were blamed on Islamism, in 1925, 1930 and 1938. The Kemalist regime responded with massive repression, banning all Sufi brotherhoods, lodges and schools, imposing (and savagely enforcing) martial law and using its expanding air force to pulverise rebellious villages.

However, it also responded, particularly at a provincial level, by enacting measures that conflated Islam and Turkish citizenship – as if only a good Muslim could be a good Turk. Inevitably, the primary cost of that conflation fell on Turkey’s Jews.

In effect, the population exchange, along with the genocide of the Armenians and Assyrian Chaldeans during the First World War, had, as in Greece, dramatically altered the demographic mix: whereas 20 per cent of Anatolia’s population was non-Muslim in 1914, by 1925 the non-Muslim proportion had shrunk to just 2.5 per cent, or one in 40. With Jews now the most visible minority, myriad forms of usually petty, but never harmless, administrative discrimination hit them especially hard.

The extent of that discrimination increased sharply in the 1930s. Ataturk died in 1938, but he had gradually withdrawn from active direction well before then. During his decline, vicious and exceptionally durable forms of antisemitism developed, in some cases associated with nationalist fantasies of a primevally pure Turkish race, in others with Islamism. Once Ataturk died, those elements of the country’s leadership that had always prized ethnic homogeneity above all else, and had never shared Ataturk’s sympathy for Jews, felt emboldened and empowered.

The result was the Varlık Vergisi Kanunu (Capital Tax Law) of 1942. Enacted to help finance increased military preparedness, the Capital Tax was, in theory, a non-discriminatory levy on assets. However, its assessment was entirely at the discretion of local bodies, whose decisions were not subject to appeal or review. Those bodies acted on the understanding that it was above all a tax on the accumulated wealth of Turkey’s Jews, which, as well as raising revenue, would advance the “Turkification” of the nation’s economy.

Taxpayers were given only days in which to settle the amounts assessed; those who could not were obliged to pay off their debt by performing hard labour at work camps set up in the harsh climatic conditions of Eastern Anatolia.

With the levies assessed at many times the value of taxpayers’ assets, thousands of Jewish families, including my own, were ruined. Left unable to pay, they were, wrote the journalist Feridun Kandemir, “despite advanced age, stuffed like cattle into freezing cold wagons with broken windows and no lights or heaters”. Only non-Muslims were deported; nor were there any Muslims among the casualties, be it those who died in the camps or those whose health was fatally broken by the ordeal.

After the war, there was some discussion of restitution and compensation. However, nothing was done – and given the horrors that had occurred elsewhere, the episode was glossed over. As those it had affected concentrated on making a new beginning, the Capital Tax sank into the past. But with trust shattered, and Islamist antisemitism steadily gaining ground, Turkey’s Sephardim – who retained an undying love for the country – yet again packed their bags.

There are, in the end, two ways of looking at the history of the Sephardim – or for that matter of the Jews. There is what Salo Baron (1895-1989), a great historian of Judaism, called “the lachrymose conception”, which all too easily becomes “enamoured with tales of ancient and modern persecutions”. And then there is that which sees centuries of “bold innovation, intellectual creativity, and against-the-odds collective survival”, allowing a minuscule group, “without sovereignty or territory, and often without coercive power, to sustain a national existence”.

It is true that the Haggadah – the text recited on the first two nights of Passover – reminds us that “there are, in every generation, those who rise up against us to annihilate us”. But it is every bit as true that in each generation there have been those who helped oppose the murderers, often at enormous cost to themselves. And just as there have been periods pervaded by death and despair, there have been golden ages and countless fresh starts, each time with extraordinary accomplishments along the way.

In that sense, the challenge is to face the past without being trapped in it. Perhaps that is why the Hebrew Bible imposes seemingly inconsistent demands. We are repeatedly told to remember – with the hammering insistence of “Remember the days of old, consider the years of ages past” (Deut. 32:7) – because Israel knows what God is from what he has done in history. We are, however, also warned against looking back, for fear of being transformed, like Lot’s wife, into a pillar of salt. We must, in other words, remember: not so as to grieve but for the sake of more surely looking forward, into a future that remains to be made.

God, said the Kabbalists, in mystical and mysterious terms Rabbi Joseph Ergas tried to explain, made the universe by shrinking the divine presence, leaving room for humanity to shape its destiny. In this renewed period of anguish, may it be one suffused, as Sepharad will always be for me, with the sweet scent of blossoms, the beauty of sun-lit mornings and the magical stillness of star-filled nights.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout