October 7: A family’s tale of escape as Hamas terrorists attacked the Nahal Oz kibbutz

The October 7 terrorist attacks in Israel shocked the world. In this gripping first-hand account, Amir Tibon describes how his family’s safety hung in the balance for hours.

The October 7 terrorist attacks in Israel shocked the world. In this gripping first-hand account, Amir Tibon describes how his family’s safety hung in the balance for hours.

6.29am, October 7, 2023

At first, there was only a whistle. A short, loud shriek coming through our bedroom window, indicating the descent of a mortar from the skies above our house. “Amir, wake up, a mortar!” my wife, Miri, said.

In an instant I was awake, adrenaline pumping. We leapt out of bed and, wearing only our underwear, sprinted out of our bedroom and down the hall, towards the open doorway of our safe room. One second, two seconds, three seconds. We reached the safe room, an above-ground bunker built of thick concrete, and shut its iron door.

That first explosion was followed by more. There had been no siren; nothing to warn us but the whistle. Something unusual was going on. We were surprised and disorientated, but not fearful – not yet. As residents of Nahal Oz, a community of just over 400 people on the Israeli border with the Gaza Strip, we had experienced situations like this before.

Unlike most of Israel, which is covered by the Iron Dome missile defence system, Nahal Oz, which was founded in the 1950s, doesn’t enjoy such protection; it is so close to Gaza that the system’s automatic interception hardware doesn’t have enough time to calculate the route of an incoming mortar.

OCTOBER 7: A YEAR ON

Australia is not the same country — but too many are in denial

Since the October 7 attacks, Australian values have been traduced. What is happening affects the entire country and the collective impact is profound.

After ‘51 days of hell’, former hostage haunted by fear for husband

Aviva Siegel longs for Keith, her beloved husband of 43 years, left behind by a deal that was struck to set her free. Her heart remains in Gaza: in a filthy room, with a weakened Keith, somewhere in the territory’s miserable ruins.

Attacks on Jews at record levels

Australia’s Jewish community has suffered its most traumatic year since records were first kept, with more than 1800 anti-Semitic incidents reported across the country, a staggering 324 per cent increase on the previous year.

No longer ‘one and free’: Nation torn apart by vile ignorance

Not since the Vietnam war, more than half a century ago, has a foreign conflict so divided the nation.

Australia has been weak when we needed to be strong

Labor’s doublespeak and equivocation have made the nation less safe as a result.

‘Genocide’ the modern-day blood libel to demonise Jews

The anniversary of the October 7 massacres compels me to reflect on the toughest 12 months of my long, happy and deeply fulfilling life as a Jewish Australian.

Two enemies, two paths – and one deadly objective

Iran relies on violence to achieve its goal of destroying Israel and its people, while the Palestinian threat is more subtle.

The tweet that captures the cowardice of Labor

There is deep sorrow still on this anniversary of October 7 among Jews of the left like me, deep sorrow and pain. And there is a sense of betrayal.

‘They’re here’: a family’s tale of escape as Hamas terrorists attacked

The October 7 terrorist attacks in Israel shocked the world. In this gripping first-hand account, Amir Tibon describes how his family’s safety hung in the balance for hours.

The nagging thought haunting the families of the Hamas hostages

A year on from the October 7 attacks, with more than 60 hostages still in captivity inside Gaza, families are stuck in a world of questions without answers.

Look around, and you’ll see Hamas’ goals of October 7 fulfilled

Israel is fighting on every front, anti-Israel protests are global, diplomatic pressure on Israel is building and its allies are losing patience. Division and mistrust between Muslim, Jewish and other populations are growing around the world. There is only one way to turn it around.

The real-life horror movie our politicians refuse to see

Raw footage, running for about 45 minutes, captures the unspeakable horror of October 7: innocent people being murdered, beheaded, hunted down, raped, kicked, bashed, burnt alive. Here’s what Australia’s leaders had to say when I asked if they had seen it.

We need to talk about the crisis in Western civilisation

The October 7 pogrom unleashed a wave of sympathy across the West – for the perpetrators.

To the political left, some kids matter more than others

In my life I never imagined a situation where the government of a free, functioning democracy such as Australia would be unable to tell right from wrong. Would be so comfortable walking in step with the wicked, unable to take a stand against evil.

Notes from a long war: Israel one year on from the October 7 massacre

This war on the ‘villa in the jungle’ was launched to test a thesis. It has been disproven at a very high cost.

In exile: how Jews became a perpetually persecuted people

Without a homeland, their community was at the mercy of monarchs, popes and prime ministers. For the writer, tracing the history of Sephardic Jews in Europe was to walk in the forever-moving footsteps of his forebears.

Our safe room has a metal plate that can cover the window to prevent shrapnel from flying in, as well as a shrapnel-proof door. The room has a security function, but families on the border use it for another purpose: this is where our children sleep. Nahal Oz is so close to Gaza that when a mortar is launched toward the community, you only have seven seconds to take shelter. When you’re inside the house, that means running to the safe room and shutting the door. For families with small children, the choice is clear: if there’s a mortar attack during the night it’s better for the parents to run to the children’s room than the other way around.

Our two daughters seemed undisturbed by all the drama. Galia, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed three-year-old, was dozing. Her little sister, Carmel, almost two, had glanced at us with sleepy green eyes when we’d first dashed into her room but then found her pacifier and returned to sleep.

This wasn’t the first time they had experienced their parents running into their bedroom as explosions mounted in the background. We never made a big deal out of it, so neither did they. It was part of our lives.

In the 1950s, the country’s leaders, such as then prime minister David Ben-Gurion, believed that civilian communities like Nahal Oz, located directly along the border, were a crucial part of the young nation’s defence strategy. Military bases, the thinking went, could be easily relocated if the country’s borders were redrawn, but civilian communities were a more durable presence. This made them critical for Israel, a country surrounded by hostile neighbours – some of whom would have liked nothing more than to redraw the new Jewish state right out of existence.

Like the young idealists who’d founded Nahal Oz, Miri and I were Zionists in the most basic sense. For us, two liberal, left-leaning Jews, Zionism meant only one thing: securing Israel’s existences as a Jewish and democratic state. The kibbutz movement was mostly moderate in its view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, advocating for decades in favour of a compromise that would allow Jews and Arabs to share this land, with agreed-upon borders. Borders that, of course, would need to be protected. Miri and I firmly believed that peace with the Palestinians would require ensuring that they had a state of their own, just like our Israel, a place where their own civilian communities, with their kindergartens, schools, clinics and homes could afford them a stable and enduring connection to the land that Israelis and Palestinians both cherish. We moved to Nahal Oz in 2016, drawn to this haven of green fields only an hour from Tel Aviv.

Hiding in our safe room on the morning of October 7, we read on our phones that Hamas, the Palestinian terror group controlling Gaza, had not just attacked our community but also fired mortars and rockets at dozens of other places across Israel. I sent a message to our neighbourhood’s text messaging group to ask if everyone was OK. “Did Israel assassinate some senior mehabel in Gaza overnight?” one of my neighbours asked, using the Hebrew word for terrorist. What else could have caused this barrage of mortars and rockets?

At 6.45am another neighbour asked if anyone else had a problem with their electricity. As if on cue, we lost power too. Everyone started writing that they were in the same situation.

Suddenly Miri and I heard a chilling sound: automatic gunfire in the distance. In previous rounds of fighting our only concern had been to evade the mortars; we had never experienced a cross-border infiltration by Hamas. But that was exactly what this noise suggested. Moreover, while the mortars were continuing to fall, their pace was slowing. Was the bombardment ending because the attackers were about to enter our community?

The gunfire grew closer. And then it was inside our neighbourhood, right near the window of our house. We heard shouting in Arabic and immediately understood what was going on. Our worst nightmare was playing out: Israel’s defensive line – the network of fences, cameras and other security apparatus that we believed would protect us from the army of terror on the other side of the border – had been breached. Hamas fighters had broken through the fences within view of the Israeli military. More than 3000 attackers had stormed the border simultaneously at more than 30 locations. They’d crushed the fence with bulldozers, blown up portions of it and sent armed drones to destroy the security cameras and remotely operated machineguns along the border.

7.10am

A neighbour sent a message to the group: “Hamas has invaded the kibbutz.” Another wrote: “There’s gunfire in the neighbourhood, they’re here.” A third replied: “Where’s the army? How come nobody is coming?”

We heard bullets smashing through our living room window. One of the terrorists was standing right outside the safe room window, shouting to the others. I’d learnt Arabic during my military service almost two decades earlier, and I had retained enough to understand: he was instructing them to search for ways to get into one of the houses – presumably ours.

We were now in grave danger not from the mortars but rather from the men on the ground. Would they be able to break into the safe room? These rooms were built with one threat in mind: rockets and mortars. The metal plate on the window was strong enough to block bullets, but would the door stand up to an assault?

Without knowing whether the terrorists were inside the house or outside it, we knew any noise we made would increase their determination to break into the safe room and find us. We had to assume that nothing would stop them from murdering us if they had the opportunity. The only other option – that they’d try to kidnap us and drag us back with them into Gaza – was just as terrifying. And so our mission was to calm the girls, who were now awake.

Carmel sat in the dark and asked if she could go out and play. Galia yawned. The gunshots had woken them up, but they didn’t ask about the loud noises at first. They couldn’t see our faces in the dark or tell how worried we were. “Girls, I’m sorry,” Miri said softly. “It’s too dangerous to leave the room. We have to stay here and be very quiet. But if you want, you can continue sleeping a little longer.” To our astonishment, that’s what they did.

I called my colleague Amos Harel, a veteran military correspondent and defence analyst forHaaretz, the Israeli newspaper where I’ve worked as a journalist since 2016. A few minutes before we’d heard the first shots being fired in the distance, Amos had warned me that this wasn’t a regular attack. “There’s talk of a cross-border infiltration, be on alert,” he texted me.

On the call Amos told me he would update his contacts in the military. But he warned that what was happening in our kibbutz was taking place simultaneously in many other places – including local IDF (Israel Defence Forces) outposts as well as the largest city in the border region. “They’re in Sderot,” he explained, “in the kibbutzim, in some military bases. No matter what, don’t leave the safe room.”

In the first few minutes of the mortar attack Miri had collected bottles of water and brought them to the safe room. But we had no food and no electricity, so we couldn’t charge our phones – our only sources of light. We also couldn’t use the bathroom, so we decided the girls would both wear diapers when they woke up, while the two of us would relieve ourselves on towels.

The messages in our neighbourhood text group were getting worse. “I have mehablim inside my house,” one neighbour wrote. “They came in white SUVs, dressed in uniform as if they’re Israeli soldiers.” I knew that this neighbour, who volunteered in the Israeli police, had security cameras in his home and could probably see the terrorists from inside his safe room.

The most difficult message to read was that of Sharon Fiorentino, a mother of three young daughters living across the street from us. Sharon’s husband, Ilan, was the security chief for our community. “I’m scared to death,” she wrote to the neighbourhood group at 7.29am. “Ilan is out there fighting them.” One by one, neighbours wrote that the terrorists were entering their homes.

When we had first heard the rockets that morning, I’d sent a quick text message to my parents in Tel Aviv. My father, Noam, is a retired Israeli army general who once commanded IDF forces in Lebanon and the West Bank. “Mehablim infiltrated the kibbutz,” I wrote. “We’re under fire.” My father immediately called my cell phone. In a terse whisper I told him our house was under attack. He said he was texting his contacts in the military. “Stay quiet,” he advised before hanging up. Shortly afterwards he called back, having had no confirmation of action from the military. “We’re coming to get you out of there,” he said.

8am

The girls woke up again. Gunshots could still be heard outside, but the house itself sounded quiet. Carmel asked, again, if she could go out to play. We explained that it was still too dangerous. Again, she and her sister responded with maturity, their acquiescence surprising us.

Even so, I suspected that we would only be able to keep them silent and calm for another hour. I hoped the attack would be over by then. Help had to be coming soon. Close to Nahal Oz is a military base, manned by close to 200 soldiers. How long, I thought, will it take for those soldiers to arrive? “We’ll be out of here soon,” I told Miri, perhaps as much for my sake as for hers. “The military knows what’s happening.”

I had no idea how grim the situation was at the base at that exact moment. Two hundred Hamas attackers had succeeded in capturing it by 8.30am. Dozens of soldiers had died, including almost 20 female field observers, or “spotters” – tasked with following Israel’s vast network of cameras along the border. In the weeks leading up to October 7 these soldiers had warned that they’d seen worrying scenes on the cameras. Hamas, they had reported to their commanders, was training for a big attack on the border communities. But their warnings were dismissed. And with the base now out of commission, there was no chance of a military force arriving quickly enough to save us.

8.30-11.30am

The girls were still quiet, playing silently with their dolls in the dark. By now there were barely any mortars falling. As the hours passed, though, we continued to hear shouting in Arabic and there was still gunfire – sometimes close to our house, sometimes further away.

Our situation was dismal but a quick glance at my phone made it clear that others in the kibbutz were facing even greater danger. In one home, the Idan family – father Tzachi and mother Gali, both 49, and their children – had Hamas terrorists pounding on their safe room door. They told the family to open it, and when the Idans refused the attackers began to force their way in. Although the locking mechanism of the safe room door in some homes was strong enough that it couldn’t be opened from the outside no matter what, with many others that wasn’t the case.

Tzachi held on to the handle with all his might, and a fight for the door ensued. The terrorists shot at it, hoping the blasts would kill Tzachi or at least force him away from the door. In the midst of the fight over the handle, a bullet penetrated the door and flew into the room. Tzachi yelled “Who’s hurt?” and realised a second later that it was his daughter Maayan. Gali touched Maayan in the dark and felt blood streaming from her head. She knew immediately: her 18-year-old was dead.

Once they’d breached the door, the terrorists yelled at the survivors to move to the living room. One of the terrorists placed a phone with an active Facebook Live broadcast in front of them, documenting the horrific scene. The whole world could now see the helpless family in the hands of Hamas. In the livestream Gali and the children could be seen lying on the floor with Tzachi seated next to them. The children were weeping and Gali was trying to console them, fighting back her own tears.

12pm

In our safe room Carmel began wandering around, looking for something to do in the dark. Then she stepped on an object and, for the first time that morning, started crying. I took her in my arms and hugged her.

I told Miri that this was all my fault: it had been my idea to come and live here, and now our lives might be ending because of it. “I never should have brought us here,” I said. I had been drawn to this beautiful place despite knowing that it was one of the most dangerous kibbutzim on the Gaza border. Miri tried to comfort me. She said the decision to move was one we had taken together. She said she loved living in the kibbutz where our daughters were born, and raising them here. “We both chose this place,” she reminded me. With nothing left to say, I told Miri how proud I was of her – as a mother, a partner and a friend. “I love you, I love our daughters, I love our life together,” she replied. For all we knew, these could be the last words we said to each other.

In the car, en route to our kibbutz from Tel Aviv, my mother drove while my father, armed only with a pistol, called several senior generals who had served under his command. None answered. As they entered the Gaza border region, a young man and woman appeared in front of them. “We saw a couple dressed for a party, wearing clothes that you don’t usually see on a Saturday morning,” my father later recalled. He and my mother let them in. “They got in and sat in the back. We asked where they’d come from and if they needed help. They were out of breath, but the woman said, ‘They shot everyone. Everyone’s dead’.”

With two unexpected passengers – Bar and Lior – now in their Jeep, my parents turned around and drove away from Sderot, heading towards the nearest city, Ashkelon, about 20 minutes north. My parents listened to Bar and Lior explain their ordeal; they described how terrorists had descended on the Nova music festival in the Negev desert and killed people as they’d tried to escape. My parents listened in disbelief and horror, growing more panicked about our safety. They dropped the traumatised young couple at Ashkelon before heading back to the border area.

As they approached Nahal Oz, my mother took a left onto 232 – the road that Bar and Lior had first taken in their attempt to escape the music festival – and then stopped the Jeep in its tracks. A biblical scene greeted her: the road was strewn with corpses. Bodies of Israeli citizens – men and women – and bodies of armed men, some of them Israeli soldiers and policemen, some of them Hamas fighters.

“I’ve never seen so much death in one place before,” my father later explained. My mother turned off the Jeep’s engine. My father wasn’t sure if they could keep going: clearly the area was extremely dangerous. Finally my mother spoke. “What if I told you about a couple,” she said, “who are less than ten kilometres from the home of their son and granddaughters, and can go and try to save their family – or they can stop and wait for someone else to do something?” It was a rhetorical question. “I’d say they have to go to their granddaughters, and they’ll never forgive themselves if they don’t,” my father said. And that was it.

10.30am

My mother turned on the engine and nosed the Jeep forward, steering between the bodies and burnt-out vehicles strewn across the road. Minutes later they had to stop again, this time at the entrance to Kibbutz Mefalsim, 10 minutes north of Nahal Oz. Here the terrorists had failed to get past the gate. By the time my mother stopped the Jeep outside its front gate, Mefalsim’s defenders had been fighting off Hamas attackers for more than two hours – and now, as my parents quickly discovered, they had driven right into the middle of that firefight. Thankfully they had pulled up next to a bomb shelter on the opposite side of the road to the entrance of the kibbutz, and managed to dash out of the vehicle and into the shelter.

With the battle raging outside, they agreed that my father should continue and my mother should stay behind: it was too dangerous for her to continue on this journey. From inside the shelter she sent a text informing me that my father was getting closer.

1pm

A Maglan force, an elite Israeli military unit, was now in touch with Nissan Dekalo, our kibbutz’s deputy security chief, who, it transpired, had been battling terrorists non-stop inside the kibbutz since 7am. Amid the fighting, Nissan had directed the incoming force to the side gate, where my father met them.

He introduced himself to the commander, Eshel, and requested permission to join the force, adding that he wanted to help them clear the kibbutz from terrorists and reach his family. Eshel and Nissan divided the kibbutz into four zones, and the soldiers, along with my father, were organised into teams that would comb and clear these areas.

2pm

The batteries of both our phones had long since died. The only sources of light were Carmel’s glow-in-the-dark dummies. The girls were growing impatient. I couldn’t blame them. I made them a promise. “If we all stay quiet, then Saba” – Hebrew for grandfather – “will come and get us out of here.” I knew how much they loved their grandparents. Little Carmel giggled joyfully, forcing us to remind her to stay quiet.

Things were quieter outside our home now, but then we heard the start of a gunfight in the distance. Something was different. This wasn’t the out-of-control shooting of the morning

hours; now there were short, controlled bursts of gunfire. “The military is here,” I told Miri.

On the other side of the kibbutz my father and the Maglan team were progressing. One of the first homes they’d reached was that of Eitan and Dganit, a couple in their sixties who had “adopted” us after we moved to Nahal Oz in 2014. When the couple opened their safe room door, my father was relieved. From the backyard of the next home, he could see our front door in the distance. He calculated that it would take the team 30 minutes or more to reach us.

4pm

As much as my father wanted to run to our home, he knew he was under the command of Eshel. They all had to remain patient and focused: they had to assume there were still terrorists inside the kibbutz. As he neared our house, my father saw our two cars completely destroyed by gunfire. There were bullet holes in the buggy on our porch. He told the soldiers, “This is where my son lives.” My father hit the metal of our safe room with his hand. Inside, we heard a bang and then a familiar voice.

Galia was the first to speak up. “Saba is here,” she said happily. My father shouted for us to open the front door. “I’m opening,” I yelled – but it took me a second to move. Even after waiting for hours in desperate anticipation of his arrival, I was still surprised to hear him, and I was worried too. What if a terrorist was hiding in our house, waiting for us to emerge?

I took a deep breath. I told Miri to put her body in front of the girls. I felt my way through the darkness to the door and I unlocked it and opened it. The light overwhelmed my eyes.

My father embraced me. We stood there, holding each other. Tears streamed from my eyes. For almost the entire time that we had been locked in darkness, I had known that he was on his way – but it was still unbelievable that he was here, standing in front of me.

Postscript

On the far side of the kibbutz was a corner home on a knoll that overlooked Gaza city. It belonged to Yaniv Zohar, a news photographer who had worked for the Associated Press; he lived there with his wife Yasmin, their two daughters Keshet, 20, and Tchelet, 18, and their youngest son, Ariel, 12. The Maglan commandos didn’t have much reason for optimism as they entered the home: the door was broken and the windows smashed. Finding the living room empty, they moved deeper into the house. They crept down a dark hallway that led to several bedrooms. When they opened the safe room it was completely dark and silent. The door was closed but unlocked. They saw blood on the floor, dozens of bullet holes all over the walls, and four bodies huddled together: Yaniv, Yasmin and their two daughters. They were all dead, killed by close-range gunfire. The commandos covered their bodies with blankets.

On the morning of October 7, Ilan Fiorentino, our fearless head of Nahal Oz security, had received a phone call from a woman who lived on the other side of the kibbutz. Her 12-year-old son Ariel, she said, had gone for a morning job and been caught in the middle of the mortar attack. He was pinned down and afraid to make his way back home. She asked Ilan if he could help. Ilan took his car and found the boy hiding along the road. He wanted to take him back home, but realised the mortar fire was too heavy. So instead he took him to his own house and told his wife Sharon to take the boy with her to the safe room. Then Ilan turned around and went out again with his M16 rifle. While the sound of gunfire echoed across our neighbourhood, Sharon sat in the darkness of their safe room, hugging her daughters with one arm and holding Ariel’s hand with her free hand.

At 6.30pm, just after we had been released from our safe room, Sharon and 12-year-old Ariel Zohar walked through our door and started asking questions.

On October 11, four days after the attack, we received the news we had all so hoped wouldn’t come: Ilan Fiorentino, our neighbour and protector, was dead.

About 1200 Israeli civilians and soldiers and dozens of foreign workers died in the attacks. More than 300 were murdered at the Nova music festival. There are currently 101 hostages held in Gaza, 35 of whom have been declared dead. Israel confirms it has killed more than 17,000 Hamas fighters since October 7, with the Hamas-controlled Palestinian authorities claiming as many civilians have also lost their lives. More than 100,000 Israelis have been displaced from their homes including along the northern borders. Many have been taken in by kibbutzim across the country.

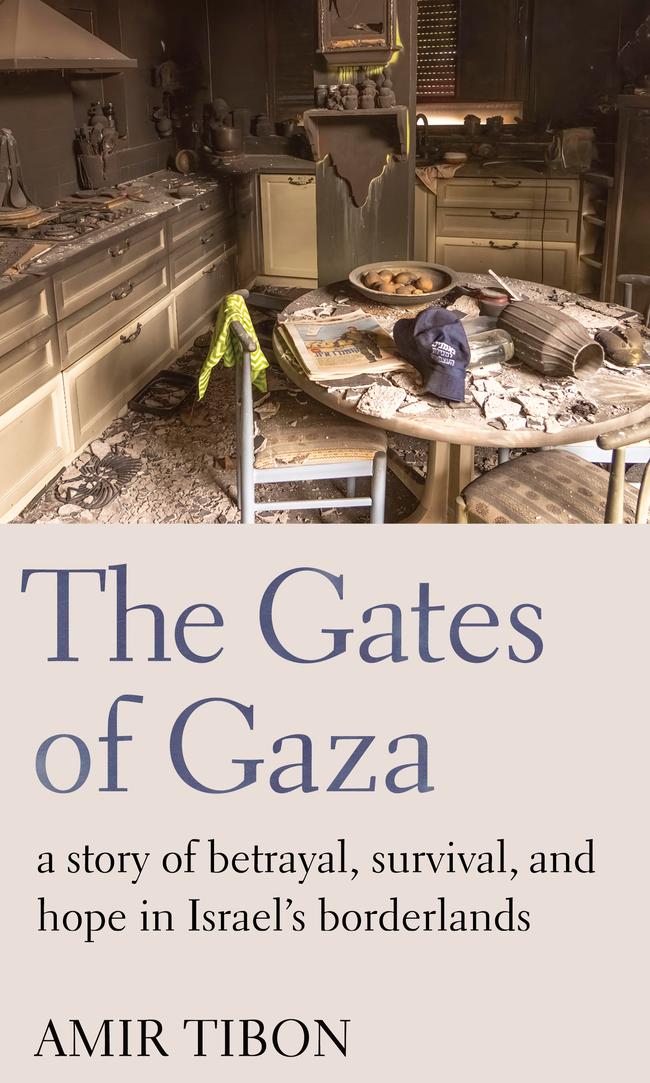

The Gates of Gaza by Amir Tibon (Scribe, $36.99) is out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout