I thought a DNA test would reveal my heritage – instead it shattered my world

I was at the airport when an email landed from the genealogy website Ancestry.com. This could be fun, I thought. I never could have imagined what I was about to read.

When I was a little girl, my mother placed everything she knew I valued in a cardboard box that had once, according to its fading label, housed an old-fashioned punchbowl … In went my black-and-yellow Richmond Football Club beanie, a vinyl single of the team anthem, a lacquered set of chopsticks my Uncle Alec had brought back from Japan, a spoken-word album called The Littlest Angel (it was voiced by the glamorous film star Loretta Young; my mother and I loved to listen to it together) and my pale pink autograph book. My late brother’s coin collection was added later. In red felt pen, right under the now-ironic words printed on the lid “Please Use Care”, Mum wrote: “DIANE’S TREASURES”.

The box has accompanied me to at least 30 addresses across three states since she packed it. It’s sitting in front of me now, bent out of shape, split down the sides and held together with faded duct tape. Part One of my life, neatly packed in a busted old punchbowl box. Only now is it clear that this is less a collection of sentimental keepsakes than a carton of mid-century secrets, an analogue breadcrumb trail that could only be followed in the digital age.

I was at Tokyo’s Haneda airport after a work trip in October when an email landed from the genealogy website Ancestry.com. Over dinner a few months earlier, a friend had talked about her DNA test. “It’s really interesting to see where your ancestors are from,” she enthused. I knew my mother’s side were German, my father’s English. Me? I’m a slighter, shorter knock-off of my tall, fair mother. This could be fun, I thought.

“Your Ancestry DNA results are in!” the subject line read, as I settled into an airport lounge chair. It had taken so long, I’d assumed my saliva was sitting in a lost-property warehouse. I went to the bar and ordered a glass of champagne.

There’s an acronym for what I was about to learn via email as planes took off and landed, passengers circled the snack bar and my world shifted on its axis: it’s called NPE, meaning Not Parent Expected. After swiping through the attached maps with Britain and much of Germanic Europe coloured in (as expected), discovering likely personal traits (correct, I don’t have a unibrow and I do have a pet), I landed on my genetic matches – a list of 18,000 people with whom I share DNA. At the top were first cousins I’d never heard of called Leonie and John*. Their surname was Anderson.

Since 2000, when direct-to-consumer genetic testing became available, more than 40 million people worldwide are believed to have taken DNA tests. Some are suspicious about their parentage, others want to find out what medical conditions they’re at risk of, and some are just keen to explore their heritage. Many have been surprised. A staggering 5-10 per cent of those tested discover a parent or parents they weren’t expecting (this includes children born as a result of sperm donation and adoption). A 2023 Israeli study found that up to five per cent of people learn they have a father other than the man who raised them.

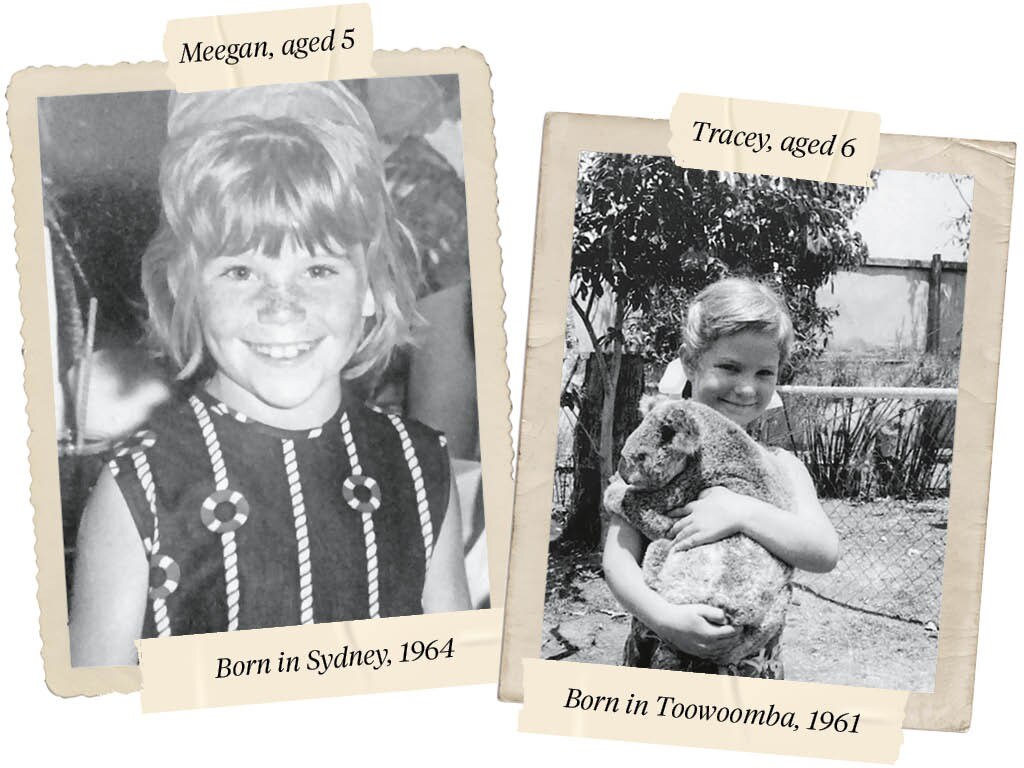

Personally, I was hoping to find an exotic explanation for my fair skin and pale green eyes (my father’s eyes were deep blue and his hair black), and always at the back of my mind was the colouring of my late brother, Geoff, born 18 months before me. Geoff’s hair was sandy and his face sprinkled with freckles. Two older brothers – born 11 and eight years earlier – more closely resembled my father.

Waiting for the DNA results, I wondered if I’d find a chunk of Scandinavia coloured in on the maternal side of the Ancestry map. I didn’t. As it turned out, my fair colouring had been determined in a love affair in Melbourne’s working class western suburbs.

The thread running through Diane’s Treasures– the chopsticks, the Tigers memorabilia, my late brother’s stuff, the opening page of the autograph book (“By hook or by crook, I’ll be the first in this book”) was a close friend of my parents whom my brothers and I called Uncle Alec. He was a constant presence in our house. Though I was born into a family of Footscray supporters, Uncle Alec and I were tied together with black-and-yellow ribbon. He called me his “Tiger mate” and, in AFL-mad Melbourne, it was Alec and I against the world. He was warm and funny and freckly. When I was eight years old, we moved from Melbourne to rural Gippsland and I never saw him again. His surname was Anderson.

Two nights after the bombshell from Ancestry landed, I hit the message link next to Leonie’s name on the website. “Hi Leonie, I hope you don’t mind me contacting you but I just got my DNA results from ancestry.com and you (and John Anderson) show up as first cousins of mine! I’m intrigued.” I offered some personal background, then asked if she was related to an Alec Anderson. “He’s my only Anderson point of reference in Melbourne,” I wrote, “and that’s from way back in my childhood.”

I said I understood if she didn’t want to respond – though in reality that was something I dreaded to the point of nausea. With my mother and father long dead, Leonie was the only person who could shed light on my origins. I saw her response at 2am. “Alec was my uncle,” she offered, along with historic addresses that matched the ones I had.

It couldn’t be chance that I was a first cousin of Alec’s niece and nephew. And it dovetailed with my freckly skin.

The jury was in: Alec was my father.

The mental health consequences of learning, via a consumer website email, that you’re not who you thought you were – that your parent is not your biological parent – has been a concern of medical professionals since companies began offering the tests. (On its website, ancestry.com warns consumers of potential surprises and directs them to a range of support services.)

To be honest, I was shocked more than surprised. That Alec might turn out to be my father had become a punchline to friends as I waited for the test results, not only because of my late brother’s colouring but also because the father I’d grown up with showed little interest in me, his only daughter. This indifference when I was a child turned into open hostility as a young adult. “You’re not even mine,” he snapped in one highly-charged phone call soon after my mother died. It was such a hurtful and ridiculous claim (that I had no way of verifying then), I wrote it off as another example of his growing vitriol and eventually forgot about it.

“Why do you talk to him?” a GP asked when I sought help for my grief. “I have to,” I said, thinking he’d misunderstood. “He’s my father.” As for Alec, I’d been joking about his potential role, but there it was, an overwhelming tally of DNA centimorgans and segments.

My father hadn’t always disliked me. Very early memories of him, while patchy, are fond ones. I remember riding on his back through the water at our fishing shack on Port Phillip Bay and sitting behind him on the couch brushing his hair. But at some point everything changed. Dad was an exceptionally talented musician. He not only played honky tonk piano like the greats of his day but could also pick up a trumpet or piano accordion and make it sing. I was in awe of his talent. “Can you teach me?” I’d ask, perched on the piano stool. The answer was always a curt “No, I can’t.” Maybe he didn’t know how to teach what came to him so naturally (he’d never had a music lesson). But to a 10-year-old girl, it was painful rejection.

That a possible explanation lay in a piece of DNA coding was at once weirdly comforting and utterly frustrating. When he’d discovered I wasn’t his daughter, why had he stayed in the marriage? And having made that decision, why did he take it out on me? Was I the problem? Could I have been a better daughter? Around and around and around these thoughts went.

Grief, the late psychiatrist Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross declared, has five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. I skipped the denial phase and headed straight to anger – at those who knew the truth but had chosen to keep it a secret; at the man who’d raised and resented me; at an NPE support group that, when I said I was a journalist, wanted me to sign a non-disclosure agreement before letting me join. But mainly I was angry at myself for taking the stupid damn test.

For my exceptional mother, Shirley, I only felt sadness. We were a team from day one. “She kept you under her wing,” recalls an old friend of our bond. To guide me through my teenage boyfriend dramas, Mum would share stories of her past loves – just not Alec, the one best forgotten, the one that produced me. She was human sunshine, but under the surface there must have been a deep well of shame. Telling me the truth would have risked unravelling the family she’d stitched together. Options for women were fewer then – and secrets easier to keep before science started blabbing.

The Israeli study into the psychiatric consequences of an NPE found that the respondents who cope better with misattributed parentage are the ones who talk about it, who don’t hold onto the shame. In the sleepless days immediately after my discovery, I couldn’t stop talking about it. I blurted it out in a work meeting, workshopped endlessly with friends and all but bailed up strangers in the street. My job for years had been to write news and human-interest stories; maybe the need to share this one was instinctive, like I was telling someone else’s story. I don’t know. Some days I was sad, others angry; sometimes I was both in the space of 30 minutes. And I needed sleep. “You look like shit,” a friend declared.

If it were a TV documentary, this is the bit where I would track down Alec, who would tell me he’d never stopped thinking about me, and we would hug it out wearing Tigers beanies. But he died in 1997. My mother had died suddenly 17 years earlier. The man who raised me died in 2000. So there is nobody alive who knows what happened – or who will admit to knowing – and, for the sake of my sanity, that’s a fact I’ve had to stuff into a brand new box and put away.

Nearly eight months have passed since the Ancestry email landed. With the benefit of time, some counselling and eventually, sleep, I’ve arrived at Dr Kübler-Ross’s “acceptance” phase. I’m glad I did the test. No new brothers and sisters have surfaced – Alec had no more children after marrying – but the truth has been liberating. Of course I’ll never know all of it. I’ll never know if Alec kept track of my life, if he knew I’d waited in vain for him in Gippsland when Richmond finally made it to a Grand Final (he’d promised to take me if the Tigers ever made a Grand Final), if he ever saw my stories. With no more information to go on, it has come down to a choice between living in the past and looking to the future. I have a career, a wonderful husband, an adorable old dog, an incredible chosen family of friends, and a life I wouldn’t change. I’ve even found some empathy for the man I knew as my father.

Leonie and I still correspond regularly and earlier this year we met, both of us nervous, in a sun-speckled cafe near her home in Melbourne’s outer suburbs. We share a love of ’60s music and dogs, and didn’t stop talking for four hours. She had printed out the Anderson genealogy for me – my ties to a family with whom I share ancestors but almost no history. Had she not responded to my initial message, I’d be floundering, certain only of who I wasn’t, not who I am. I will always be grateful to her.

Early in our email spree, I pointed Leonie to my Instagram page and a picture of my brother Geoff and me sitting with Mum, all of us dressed in our Sunday best. Geoff died of cystic fibrosis just short of his 19th birthday, and long before DNA testing. “Ginger Meggs!” a friend had remarked in the comments. Those freckles of his reminded me of Alec’s face; the cheeky smile reminded me of Alec’s mischief in convincing me to be the only Tiger in a family of Bulldogs. Geoff looked nothing like my older two brothers – but he did look like the man I now believe was our warm, funny, freckly father. “No mistake there,” said Leonie.

In the absence of science, and fed up with secrets, I’m calling it: Shirley, Alec, Geoff and I are a biological family of four.

We live in a box in the garage.

* Not their real names.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout