DNA and the gift of finally knowing Dad

Two girls are born in different states, three years apart. More than half a century later, they ask for the same birthday present. What follows will change their lives.

Hope was a fading commodity when Tracey Howell decided to find her father. A blank space on her ageing birth certificate, the nameless man had never featured in her first half century. And by the time her 57th birthday neared, and she had located and then lost her birth mother, “I’d kind of lost faith in humanity”.

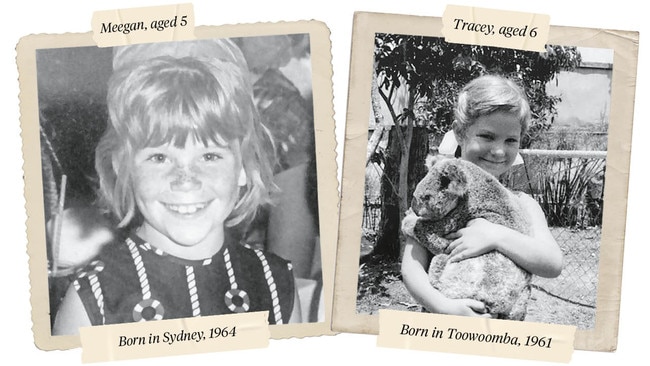

But a trace of that faith somehow lingered and five years ago she began a tentative search for him. “I thought one of them must have been OK,” she says of the birth parents she never knew existed until she was 25. In an unexpected conversation in her old family home in Toowoomba, she had learnt from the couple who raised her that she was adopted as a baby. The news floored her, but the urge to track down her birth parents would remain for decades.

In early 2018, by then a wife, mother and grandmother, Tracey asked her husband Graeme for a DNA testing kit for her birthday. “Deep inside,” she says, “it was, ‘What if I found my father?’” While the test was much more straightforward than the path that had brought her here – she just had to spit into a small plastic tube and cover it with a cap pre-filled with stabilising fluid – even when she posted it back weeks later, she did not really believe she would find her father. Yet she sat down in her Queensland home soon after and wrote a letter. Lengthy and tentative, it outlined her life and her loves, but more than anything it was infused with longing. As she signed it and sent it out into the world, she had no idea of the emotions that would follow.

Meegan Hall’s birthday was also approaching. An ebullient teacher with a huge love of family, she had devoted her career to youngsters. “I’m an only child. I grew up overseas and interstate, away from family,” she says from her memento-filled home on Melbourne’s outskirts, a warm space where the framed war record of her great grandfather dominates a dining room wall. Born in Sydney in 1964, she had an itinerant start. Her father’s army job took his small family around Australia and Asia, their loop only halting in Melbourne so that Meegan could complete her education. “When I used to complain that I was an only child, my mum used to joke, ‘You’ve probably got siblings all over the place because your dad was such a lad.’”

By the time she was approaching middle age, her mother had died, her father had remarried and moved to Tasmania, her adored boys were adults, and she had time to explore her genealogy. Keen to know more about her mother’s side, and hoping to unearth distant cousins, for her birthday in April 2018 Meegan also asked her husband to buy her a DNA test.

Tracey did not open her kit for weeks. With a life packed with children and grandchildren, and busy, fraught days as a child welfare officer, around Mother’s Day in 2018 she finally found the time to send her DNA on a journey that might lead to nothing. That she would even take this step on some level seemed extraordinary. In her 61 years she has known the love of a long marriage and the devotion of three children, but she is also marked by her early years. She too had an itinerant start, moving around Queensland for her father’s work. She remembers her childhood as harsh, her mother as cruel. “When she called me a bastard regularly I really didn’t know what she was talking about.”

Married at 19, she left her home town the following day. Only when she was pregnant did the mother who raised her reveal in a brusque conversation, still traumatic to recall, that Tracey was adopted. But she provided scant details.

The floods that ravaged Queensland in 1977 destroyed most official records of Tracey’s origins. Only when she was in her early 30s did she finally receive her birth certificate from the state government. From that precious document she learnt her mother’s name and that she had given birth to her at 16. Her father was 19, of English descent, but unnamed. On the only document that linked Tracey to her birth, the space set aside for her father’s name was covered with an instruction: “Not to be used for official purposes”.

Tracey’s father remained as unattainable as a shadow, but her mother might now conceivably be found. And then, like that, she was. After just two phone calls she was talking to the woman who gave her life. They soon met, joyously, and her newly discovered mother even moved towns to be near Tracey and her family. But the joy was short-lived. “We were struggling but we set her up in a flat, and I think she only stayed for two or three months and she sold the lot without even telling us. Without even telling her grandchildren, she left,” she says. “She wasn’t a good woman.”

By the time her birth mother died several years later their brief connection was all but severed, although Tracey maintain a good relationship with her newly found grandmother. She was no closer to learning about her father, however, apart from one snippet gleaned from her birth mother that she protected zealously. “When I asked her about my father, the most information I ever got was that I was conceived in Queens Park in Toowoomba.”

When Meegan received her DNA results in July 2018, she was initially perplexed. She’d been searching for maternal links. But most of the distant relatives to whom she was connected, and who had also provided their DNA samples, were from her father’s side. Amid her mix of German, Irish and British ancestry, one anonymous link was particularly intriguing. An unknown woman who had also submitted her DNA for analysis was a tight match to Meegan genetically – and much closer than a cousin.

“I thought, she can’t be my sister, that’s not right. She’s not my mother. Maybe she’s my aunt? Maybe one of my grandparents had another child?” On a weekday in August 2018, Meegan messaged the faceless genetic match through the company that had arranged their tests. “After getting my DNA results… they put me in touch with you!” Although her tone was cheerful, she had no idea how they might be linked.

Days later, the woman replied. “I was conceived in Toowoomba. I don’t know who my Dad is but my grandmother points to him being a Shaw from Toowoomba, born 1942-1944 and possibly an electrician.” Only three years older than Meegan, she was neither her mother nor her aunt. “I was adopted out, and I really doubt if my birth father was even aware of my existence… I’d love to hear any further information you can give me. Thanks so much, Tracey.”

After the two women spoke by phone, Meegan called her father. “I asked him, ‘Would you have had unprotected sex in Queens Park in Toowoomba in 1960?’ And he said, ‘Oh, probably.’”

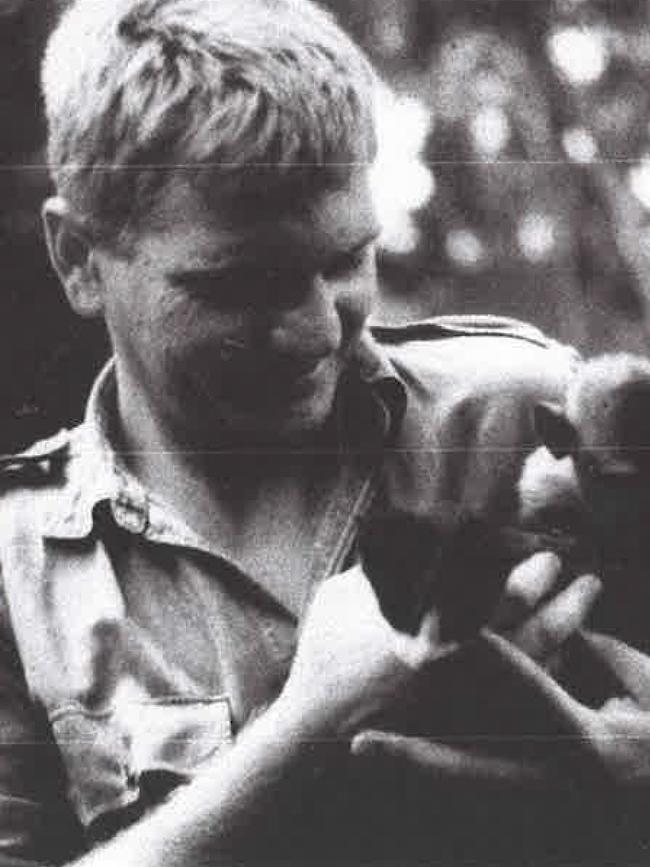

At 79, Darryl Shaw is a laconic man, a very decent bloke according to his daughter, and who sometimes uses humour to cloak his abiding love of family. A veteran of Vietnam’s Battle of Long Tan, he, too, has been scarred by his history. The post-traumatic stress so common to his contemporaries is now compounded by kidney disease, which is slowly ending his life.

Born in 1943, he was raised by an abusive father and left school at 13 to help his then single mother raise his younger siblings. So that he could be paid an adult wage he lied about his age to obtain a series of jobs, which eventually led to work at an abattoir and an electrical shop in Toowoomba in the early 1960s. “He was a bit of a larrikin,” says Meegan, “so to get out of trouble and out of Toowoomba he joined the army.” By 23 he would be commanding a platoon of Australian soldiers in Vietnam. But before that he was a young lad, tall, blond and blue-eyed, who would attend dances at a Toowoomba hall, sometimes ending the evening in a nearby park with one of that night’s dance partners.

Learning that one of those liaisons had likely resulted in a daughter who had lived almost 60 years without knowing him did not lead to jubilation. “He was very upset,” says Meegan, “because he is very critical of men who bring children into the world and then don’t stick around to raise them. Because the man who raised him did that, he left. He’s always been very adamant that if you bring children into this world you bloody well stick around and do everything you can for them.” Hearing about Tracey’s difficult childhood only compounded his emotions. From his home in Burnie, Tasmania, where he was largely confined because of illness, Darryl spent long hours pondering the past and its consequences. Usually steadfast to the point of being bombastic, he was suddenly subdued. In early September 2018, from her home on the other side of the country, Tracey wrote to him.

“Dear Darryl,

I have to preface this letter by saying that I don’t want you to have any obligation in the world to write back, to phone or to include me in your life, or the life of your family. This whole thing has been a whirlwind for me – so I can’t imagine what it’s been like for you.”

She penned three long pages, outlining her life, her loves and her brief and fractured relationship with her birth mother. “I never blamed her, or anyone for my lot and certainly I never thought of you in any other way than ‘that poor man who probably has no idea he even fathered a child’.”

She told him about her three adoring children, “amazing adults, hardworking, well-mannered and beautiful people”, her time as a mature-age student, that she enjoyed steak with Worcestershire sauce, and that she had parachuted and climbed a glacier. She enclosed photos of her grandchildren (“your beautiful great grandchildren”) and she concluded with some poignant words that she tried to pass off as light-hearted. “Again, no pressure, no expectations. I just wanted you to know that it may have been a moment of passion 58 years ago, but I am so so thankful for being here.”

Meegan was ecstatic. “I do so hope that my dad Darryl Shaw is your dad also,” she had messaged Tracey a week after their first contact. “I think we all need to know where we come from.” Now everyone around her was sounding caution just as she was working out how soon she could meet Tracey. “Once you open up these things it’s a Pandora’s box and you can never put it back,” her father advised. Friends urged her “to go slow, you don’t know what this person is like. And I was like, ‘No, I’ve got a sister, I’m going to embrace her’. I did exactly what they said not to do.” Two months after discovering one another, the two women prepared to meet.

Tracey’s family was also sceptical in the weeks before their planned Sunday lunch at the Kingaroy RSL club. She wanted Meegan and her husband Peter to stay that night at her nearby home, but her husband Graeme pressed her to keep some distance. “He remembered how bad everything went with my mother.”

The reality of finding a sister, however, proved much more enduring as the two women spotted one another across the restaurant. “When I saw her walk in I just got up and almost started running to her,” says Tracey. “As soon as we saw each other,” says Meegan, “we just hugged and burst into tears.” They took photos (“I showed everyone,” says Tracey,” whether they were interested or not: ‘Look, this is my sister’”) and as they joined the table where most of Tracey’s immediate family was waiting, they noticed that they were carrying identical handbags. They were also wearing the same perfume, and when they compared their hands (also similar) they had virtually identical eternity rings. Both women had worked with children, and both were brimming with life. Tracey, says Meegan, “was just so open, no frills, no bullshit”. And she looked just like Darryl.

“It was a disclaimer, if you want to call it that,” Darryl says of that letter that he received from Tracey in the spring of 2018. But while Tracey and Meegan rejoiced in one another’s presence, he was unsure about a meeting that included him. “I said to him, ‘It’s not about you. You’re at the end of your life,’” Meegan recalls of the aftermath of her Kingaroy visit. “‘But this woman has been searching for her father for 30 years and she needs closure. And before you die she needs to meet you, to know who you are and who she is.’”

Then Covid intervened. After 60-odd years, Tracey had to wait two more years, until the start of 2021, to meet her father, and even then Darryl was reticent. In a photo of that momentous January meeting at his home, Tracey, dressed in vibrant orange, her sunglasses perched atop her head, is leaning into Darryl and smiling. He has his arm around her protectively, but his expression is sombre, and he looks pained. “She was so gentle with him,” says Meegan. “At one point Dad apologised and she said, ‘Oh Darryl, there’s nothing to apologise for. You didn’t know I existed.’” And despite his reserve, as he sat in his lounge room with the two women, even Darryl could sense the emergence of a bond. “The three of us together a little bit melded in with one another,” he says when asked if he noticed any resemblances.

Even more months would pass before the cracks that ever so slowly appeared in his veneer exposed his true feelings. Following a bad fall at the start of 2022, and after so long as a father of one, he asked his wife: “Can you call my girls and let them know what’s happened.”

Tracey and Darryl have not seen each other again.Theyoften text and sometimes exchange gifts – she loves the children’s book he sent her, My Dad Thinks He’s Funny – but they don’t regularly phone and there have been no more visits. “I guess the reason that I haven’t rung is that I am scared to get closer and then know I am going to lose him,” says Tracey. “I’m stuck in the spot where I’ve got his phone number, where I haven’t rung him and he hasn’t rung me. But part of me feels a little bit like a fraud, that I shouldn’t love him as much as I do because I didn’t grow up with him.”

In this story, where a beginning coincides with an ending, the price of finding an unknown loved one is the possibility of soon losing them. But for both of Darryl Shaw’s daughters, the benefits that have flowed from their birthday gifts five years ago are invaluable. “It’s always played on my mind that when he [Darryl] dies, that will be it. I won’t have any family really, no one that you can pick up a phone and just chat to,” says Meegan. “I feel less alone in the world. It’s ridiculous because I‘ve got a great husband and two beautiful sons and I’m surrounded by wonderful women friends. But there’s always a little bit of grain in the oyster that I don’t have any family that I am close to, and now I do.” Tracey, her lifelong sister of just four years, is now the first person she calls for important moments. “It’s added a dimension of joy to my life that I have never experienced.”

And for Tracey, who has lately been calling her father Dad more often than Darryl, there is the reassurance that, even when they are tinged with sadness, some of life’s surprises can be extraordinary. “I was of the opinion I would never, ever know who my father was,” she says. “It’s absolutely a love story.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout