How a DNA test united siblings separated by fate, and half the world

At 23, Will Seitam is simply overwhelmed at the joy he has found when he wasn’t even looking. On an unexceptional day in 2023, a message flashed on the screen of his phone. It was short, unexpected and startling.

Sometimes you realise what you’re missing only when you find it. Will Seitam learned this belatedly on an otherwise unexceptional day in early 2023 when he awoke in his Sydney bedroom after a big night out and groggily flicked on his phone.

A message flashed on his screen. It was short and unexpected … and startling. “Hi!” it began, the friendly greeting belying the shock of what followed.

The five words were far from bleak but they were seismic, and they would change the way the young Australian university student saw himself.

At 21, Will was the product of a happy upbringing. He lived with his parents in a spacious home on Sydney’s north shore, played cricket and guitar, and loved writing.

With plenty of cousins, mates and neighbours, he’d been cocooned in their warmth and love for almost his entire life – although for as long as he could remember he also knew it was not always thus. Until he was 5½ months old, he was cared for by a doting foster mother in his home town of Seoul, where he was born as Kim Ho Seong in October 2001 to a couple who had already split up.

“There was a lot of stigma attached to single mothers in South Korea at the time I was given to an adoption agency,” says Will, who is now 23. As bureaucratic options and obstacles were assessed and surmounted and his future was determined, he was taken in by a foster mother.

In late 2001, a Sydney couple, who had spent two years seeking to adopt a child, were informed their dream was about to be realised.

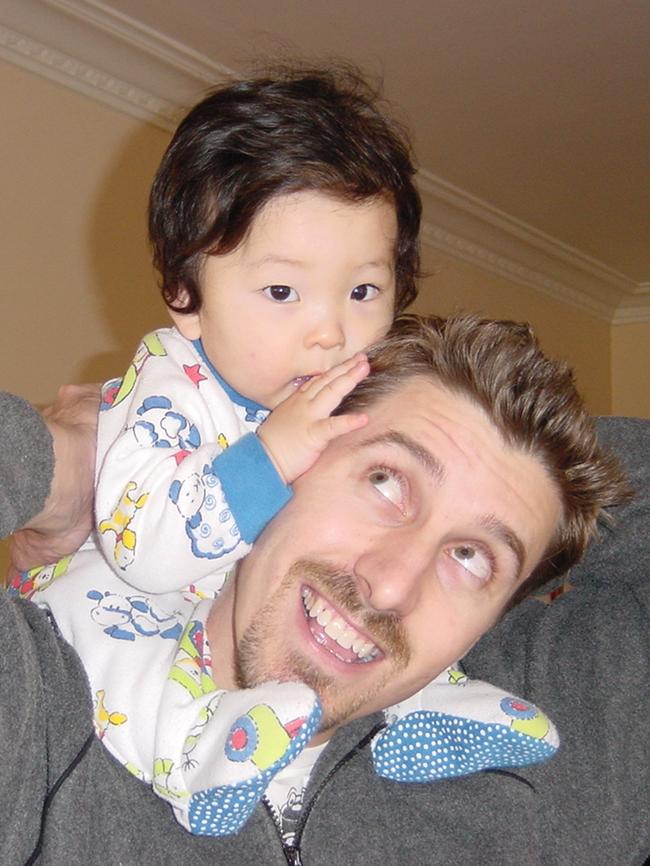

In April 2002, in a forgotten room in Seoul, they cuddled their son, who they named Will Ho Seong Seitam, for the first time.

“We had never really had a child in our care before,” says Drew Seitam, a Sydney IT specialist who, with his wife, Kathy Leach, who also works in IT, spent their first night of parenthood awake in a hotel room, gently prodding the newest member of their instant family or placing a finger above his lip to check that he was still breathing.

“He was five months old and just a little cherub,” says Kathy.

Their circle of joy was expanded not 36 hours later when, clutching their only child, they disembarked from an overnight flight and 25 overjoyed, balloon-waving relatives greeted them at Sydney airport.

Underwhelmed

So began the next part of Will’s life as the focal point of a tight, contented unit. “They are some of the most loving people you will ever meet,” he says of his parents, and his disinclination to learn about his birth family. “I feel very lucky to be in such a loving environment … I don’t need anybody else.”

Nor had his parents overly pondered delving into his origins. As Kathy says: “We were busy living life.” They did ensure, though, through a personalised book, that their son was always aware that he was born in South Korea, that he was adopted, and that he was loved. A few years ago, they even travelled to Seoul, where Will was reunited with his foster mother, Mrs Yu, who hugged him and sobbed that, of the countless children for whom she had cared, “you’re the only one that has ever come back”.

By his late teens, Will was grounded by his family in Sydney, happy and secure. And then the nation was gripped by the Covid pandemic. Lockdowns had their own strange rhythms and quirks, one of which was an uptick, possibly due to so many people having so much free time, in home DNA tests, which lingered into the following years.

Will and his parents were pondering their personal lineages when they each spat into a tube late in 2022 and sent their samples away to be tested. When Will received his DNA results weeks later, he was underwhelmed. He was, he learned, almost entirely Korean, and a tiny percentage Japanese. “I must be the most boring man on Earth,” he laughs now.

He figured his DNA probe was over. Then, months later, he awoke to that message on his phone one Sunday morning. “Hi!” a young American woman, Riley Difatta, wrote to him. She, too, had recently done a DNA test, and had just received her results. “It says we are siblings.”

Astonishment

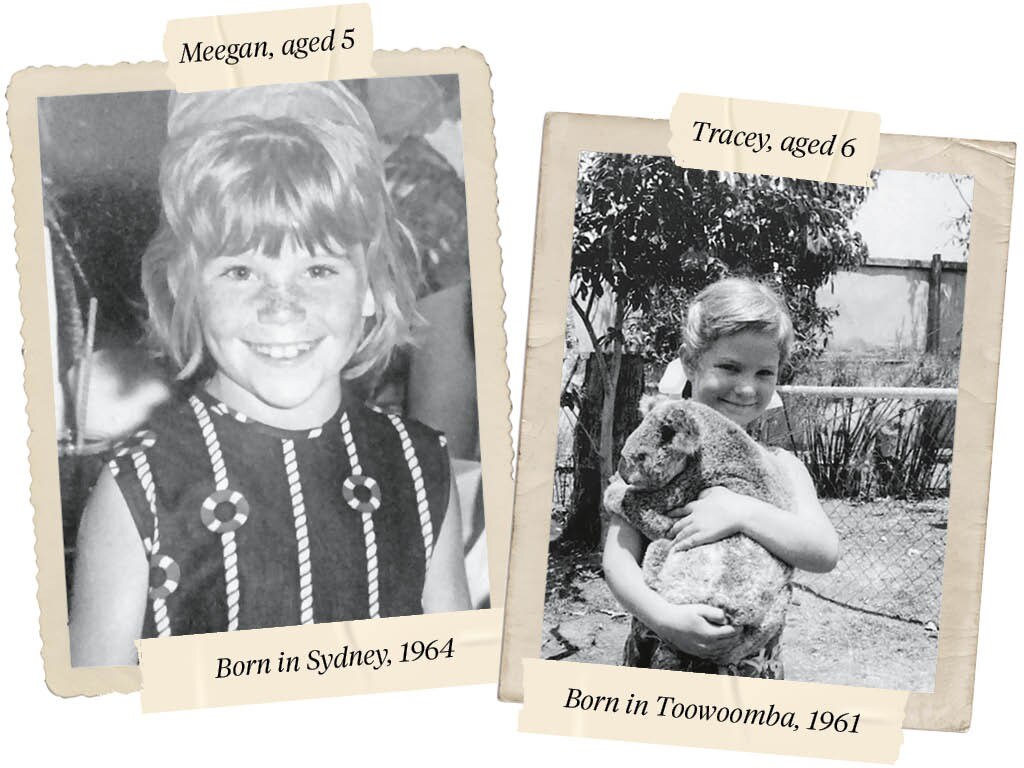

Riley Difatta was also born in Seoul, almost a year to the day before Will. She too had been fostered for several months before being adopted by another loving family, and raised with two siblings, including a non-biological adopted sister, in Detroit.

She always knew she was adopted. “A lot of people will think it’s a plan B,” she says now. “But it has obviously worked well for us.”

Like Will, though, she had no great yearning to probe her roots. “I always had some curiosity about it but I wasn’t dying to know everything. I figured I was Korean – it was very obvious.”

Her life changed on a whim. In November 2022, her mother bought a DNA test because it was on sale. “And I happened to be home in the holidays,” says Riley, who had moved to Baltimore to study before landing a job in marketing in Washington DC, “and she said ‘You might as well try it’.”

She pondered briefly about finding a half-sibling and no longer being the youngest in her family, but mostly Riley figured she might learn something of her origins.

When she opened her results early in 2023, she discovered she was mostly Korean, and a tiny portion Japanese. As she read further, she saw, to her astonishment, that her DNA had been matched to a young man – she had no idea where – and that they shared the same parents.

“I was in shock. It was the craziest day of my life,” she says of the news that she had a full brother, a thunderbolt that quickly had her in tears.

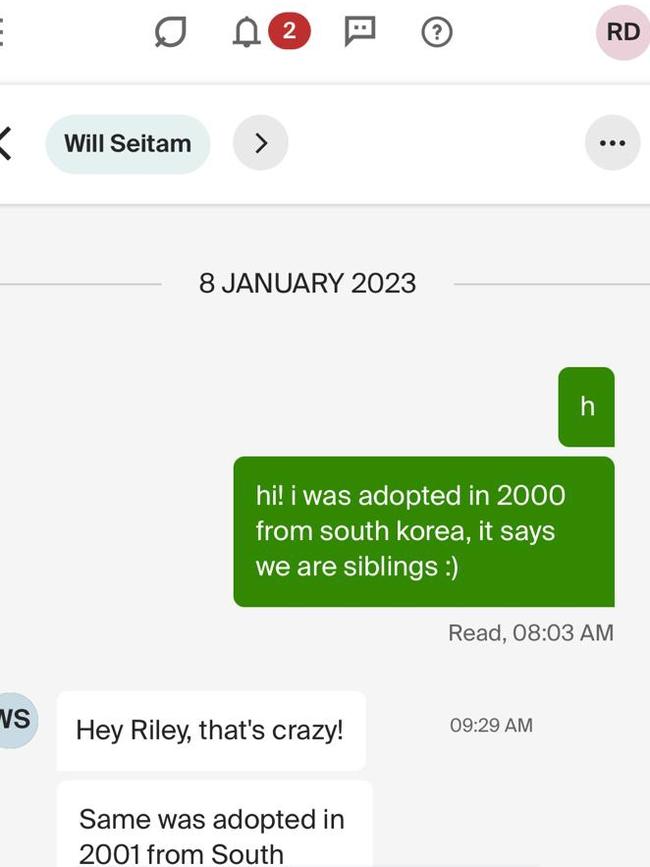

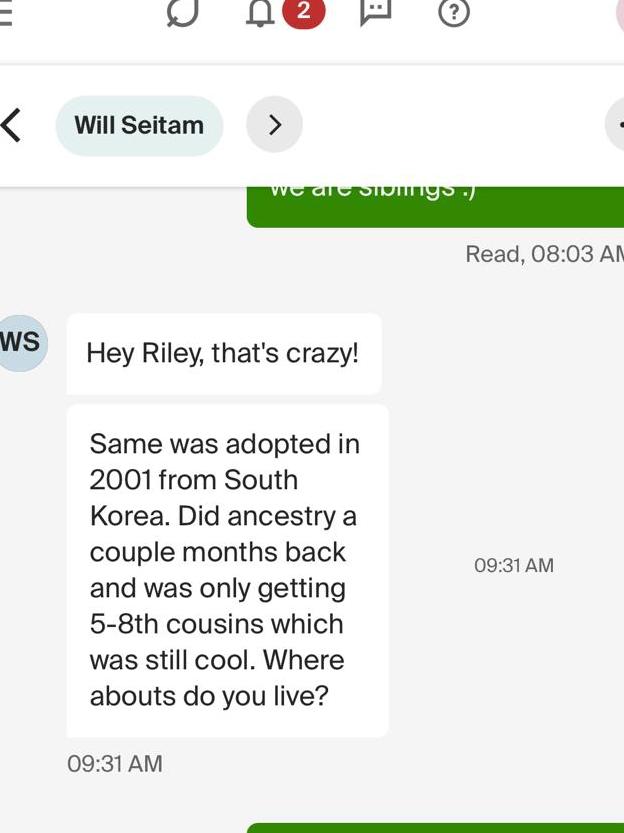

Within minutes she was messaging her fraternal match, so excited and so shaken that her first note was accidentally sent when she had just typed the letter ‘H”.

“Hi! I was adopted in 2000 from South Korea, it says we are siblings,” Riley wrote on her second attempt, the smile she attached at the end of her message hinting at the mix of bewilderment and excitement she felt.

Over the following few minutes, armed with scant information, two young strangers, separated by continents and decades, took the first steps towards forging a relationship as siblings.

Messaging from their family homes in the US and Australia, they learned they were born in the same month, a year apart, that they had each been adopted from South Korea, that they were both either at university or had just finished.

Harnessing more of the technology that had brought them together, Riley also did a quick search of Will online. “I found his Facebook profile and it was a picture of him as a child and I was ‘Oh my gosh that’s me’.”

Having been content not to delve into his origins, for the first time in his 21 years Will was suddenly speaking to someone who shared his DNA. “I was like, holy shit,” he says. “I didn’t really know how to digest it.” He ran to the kitchen, where his father Drew was making breakfast, “and he started crying, and I was crying as well … It was happiness.”

Later that day, the siblings spoke on the phone for the first time, and soon after they were joined by their ecstatic families on a video call.

Relationship

At the end of that momentous year, Riley flew to a continent that she had never previously thought might figure in her story, to meet her younger brother for the first time. “I just wanted to throw my bags and run,” she says of spotting him at Sydney airport.

“It was wonderful.”

The siblings spent the next 10 days together. “I like to think I’m a fairly laid-back person, and she comes into the terminal and I saw her and it hit me and I started bawling,” says Will. “It was weird looking at someone and thinking you’re the girl version of me.”

For Will’s delighted parents, the similarities were stark. “We have never had any nature versus nurture in our family,” says Kathy. “When I saw them standing the same way and gesturing the same way, my heart just exploded.”

On a weekday morning in January this year, the Seitam-Leach family was back at Sydney airport. The greeting party was smaller than when the trio emerged from the arrivals hall 23 years ago but there were still balloons and there was still joy as Will and his parents waited for Riley to emerge from her long flight from the US for the start of an extended stay. After decades apart, the siblings are living in the same house for the first time.

While their story about family has taken many turns, this latest chapter presents its own quandaries. Is Will still an only child? “Well he’s our only child,” says his delighted father. “It’s just that he has a sister.”

“I like to think I’m a fairly laid back person, and she comes into the terminal and I saw her and it hit me and I started bawling. It was weird looking at someone and thinking you’re the girl version of me.” - Will Seitam

Also unclear is a descriptor for the relationship that connects Will’s parents to Riley. “We’re obviously not her Mum and Dad. She has got a beautiful family over in Detroit,” says Kathy. “I don’t know whether we will give it a name, but we’re going to be very close.” Or as Drew says: “It feels like a special unnamed relationship, that she has completed our family.”

Unexpected joy

This is not the ending Will’s parents expected when they brought him home 23 years ago. If anything, it has added to their happiness. “I find it hard to talk about it a lot without choking up,” says Drew, 56. “We had hopes and dreams for Will that maybe one day he would find a sibling but probably it would be a half-sibling. We never really imagined this. We never really thought of the possibility of him having another sibling who was also adopted and had the same lived experience.”

For Riley, finding her brother has brought a bounty of unexpected joys. “You learn when you’re adopted that blood doesn’t necessarily make you family and that it’s what you make along the way.” While that’s still true, “finding Will, I think yeah blood does that too”.

For Will, too, finding his sister has been life-altering. “It’s changed my whole perspective. Knowing there’s someone out there who shares my blood … who grew up on the other side of the world.”

At 23, he’s suddenly an only child and a younger brother.

He’s talked with Riley, who has quickly become one of his favourite people, about seeking their birth parents one day, but he still has no great yearning.

With a sibling in his life, he’s simply overwhelmed at the joy he’s found when he was not even looking.

DNA testing - did you know...

When Time Magazine nominated the retail DNA test as its invention of the year in 2008, few might have imagined the popularity that would ensue.

Just over a decade later, more than 26 million people had added their DNA to four leading commercial ancestry and health databases, according to a report in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Technology Review.

That figure is likely to have easily surpassed 100 million people by now.

The first at-home genetic tests were produced by a British company in 1996, allowing consumers to access their genetic information via mail order.

As tests became more popular, they also became more affordable. Between 2007 and 2012 alone, the cost of home tests dropped from $US1000 to just $US99 as growing numbers of people sought to trace their ancestry or determine parentage. For others, there were underlying health concerns as they sought to discover whether they were carriers of a genetic disorder, or to predict future susceptibility to a disease.

While ease of access has made genetic testing ever-more popular, it is not without concerns. “Genetic testing, along with the methods by which a genetic test is offered, has both benefits and pitfalls,” the National Health and Medical Research Council noted in its 2022 statement on genetic testing.

“Individuals may undergo Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) genetic testing out of curiosity for seemingly trivial things, such as to discover more about their ear wax or whether they possess genetic variations for curly hair, allowing greater engagement and appreciation for science and for what makes them unique. However, of potential concern is the packaging of such tests ‘for fun’ when they also offer findings that affect, or are considered as affecting, clinical outcomes.”

The council’s statement noted that while growing enthusiasm for home tests was encouraging “as it suggests a willingness by individuals to engage more actively with their own health and wellbeing … the provision of unnecessary and/or inaccurate DTC genetic tests has the potential to produce an expanding cohort of ‘worried well’ and place unnecessary strain on Australia’s health system.”

For adoptees, the tests are of particular significance as they are “one of the few ways adoptees can open doors to their genetic health history,” according to the US’s National Human Genome Research Institute.

“While not a traditional care model, (at-home testing) allows adoptees a way to begin to understand their genetics and take action based on their results. These results are often the only glimpse that adoptees have of their biological make-up and can be meaningful to them even if their results are inconclusive.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout