They were told their baby would die before she turned three. How did she defy the odds?

Diagnosed with a life limiting illness at five months, doctors told Jess Schonberger’s parents their first-born would not see her third birthday. What happened next has astounded everyone.

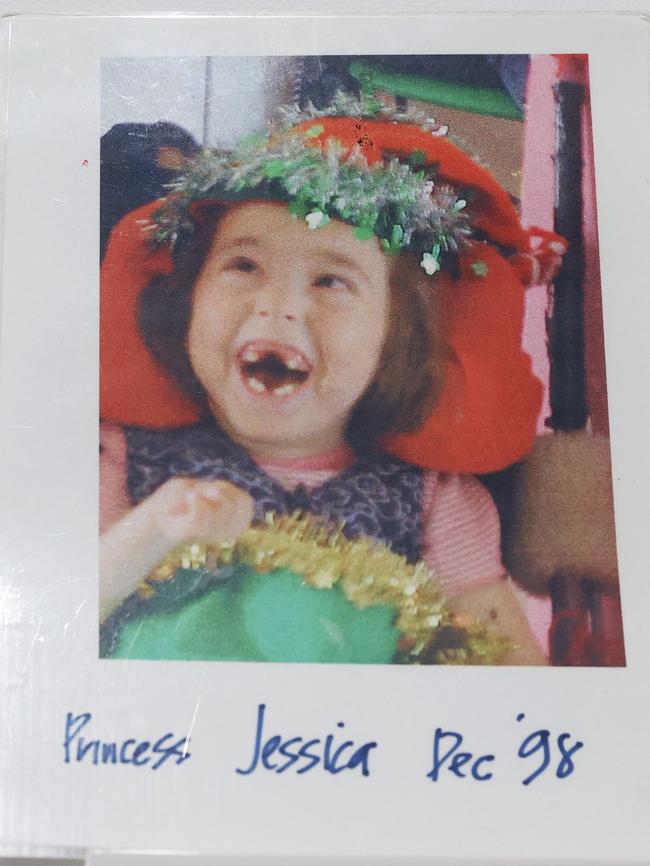

On her most recent birthday, Jess Schonberger woke to the sounds of joy. In her balloon-festooned Sydney bedroom, her celebration-loving family gathered around her for a photo and produced a bounty of gifts: a David Walliams book, a watermelon-scented candle and a robotic toy Furby. Then they performed a rap rendition of the happy birthday song, hoping to disguise the original version, which Jess has never liked.

They seem to have succeeded because Jess responded as she usually does to moments of delight, widening her eye, raising her brow and gently grinning, a reaction that elicited even more joy from her family. There was a birthday cake, too, but Jess could not eat that. Neither could she play with her carefully selected gifts. Yet this November day was an occasion not only of happiness but also of wonder and of pride.

Because in another time Jess was diagnosed with a rare and life-limiting genetic condition and doctors told her parents she would not see her third birthday. Devastated, they set about making the rest of her life safe, happy and warm. Encircled by love and supported by a growing list of medical aides and medications, she reached her first birthday. Having never crawled, she turned two. Without uttering a word, she turned three.

Each birthday was momentous. But this one in late 2024, marked with a book that had to be read to her because she cannot read and a scented candle she could not admire, was even more special. Because on this birthday, after three decades of intensive care, Jess turned 33.

“It’s huge,” her mother, Debbie, declares fervently, weeks on, of her daughter’s milestone. “I just want to climb up a mountain and scream ‘woo!’ ” She beams as she says this, perched on a couch in the family’s living room with its mix of framed photos and trophies, and a counter covered with a small fraction of the medical supplies needed to protect and sustain her immobile daughter. Then, in case her jubilation is not clear enough, she adds: “We just want to dance.”

To an outsider, Jess’s story is hard and unimaginable. No one who holds their healthy newborn envisages being warned about that child dying unbearably young. Or that same child somehow reaching adulthood virtually blind, with a twisted back and with so many disabilities that the rest of her life is almost entirely confined to a bedroom that is essentially a hospital room, supported by life-saving machinery.

To members of her family, however, who have spent so much of the past 33 years nurturing Jess and fighting for her welfare, hers is a tale of wonder and inspiration.

Yes, caring for someone with numerous needs is constant and exhausting, even with the assistance of a dedicated long-term team, many of them nurses. Jess is here today because there has been someone by her side constantly for decades. But her unlikely life story also has lobbed some powerful and positive messages to her family, teaching them patience, showing them how to live in the moment and to appreciate life’s minutiae.

But mostly to be grateful for what you have.

Jess was born in late 1991 with a new perfect Apgar score and tacit expectations that she would live a long and fruitful life. Her parents were newly married, in their early 30s and excited. “Things were going well,” says her father, Earl, who had an IT business. Debbie was working in childcare. Jess was their first-born. “We started off our lives with all the wishes and hopes of what people would normally have.”

Within months, however, they felt something was wrong. “We hadn’t had a child before so you don’t know for sure, but you got a sense that something wasn’t quite right with her development because she was quite floppy,” Earl says. “You would lie a baby on their tummy and they start to lift their head up a little bit and look around a bit. She wasn’t doing that.”

A doctor reassured the couple that this was just a glitch in their baby’s development. But when she was still not thriving at five months they took her back to the pediatrician. In an extraordinary coincidence, that same specialist was treating a child for Canavan disease, a life-limiting genetic neurological disorder where the brain’s white matter deteriorates, preventing nerve signals from properly transmitting.

The condition, whose symptoms include blindness, seizures, a failure to thrive and difficulty swallowing, is devastating. People with the disease cannot move or communicate and many die in early childhood. But it is also so rare that, at the time, the pediatrician’s young patient was the only known case of Canavan disease in the country. Then a urine test suggested that Jess was likely to be the second.

The Schonbergers knew nothing about the condition that would henceforth dictate their lives. Genetic testing was not then available, and unaware that both she and her husband were carriers of a disease of which they had never heard Debbie did not undergo a prenatal CVS test that, years later, ensured that their second child, Ariel, was not affected.

A battery of hospital tests soon confirmed Jess’s diagnosis. Compared with the tenderness with which she is enveloped today, the news was unexpected, its delivery cold. “It was very clinical, there was no warmth. There was no support, no social worker, no anything, just the diagnosis: ‘You are only going to have her till she is three. She is not going to walk. She is not going to talk. She is not going to sit up,’ ” Debbie recalls of that meeting with a specialist more than 30 years ago. “Our whole world just crashed.”

Jess’s life became the focus of their lives, with increasing intensity. As with all children in their first year, all her needs had to be met. But unlike most children as they age, that list never really abated. She was tended, watched, ministered, bathed, moved and medicated. She developed seizures. She began to lose her sight.

“Those first years were very hard,” Earl says of a period that included many dashes to hospital.

“She nearly died at one point. But then she got to one. Then she got to two years, and they said: ‘Well she’s two, maybe she has another year.’ And she got to three and they said: ‘Maybe five.’ And she got to five and they said: ‘Maybe 10.’ And then she got to 10 and they stopped telling us.” Was it love? Luck? Caring? Or a combination? No one is clear about the reasons for Jess’s comparative longevity. But while it seemed miraculous, it was hardly fairytale.

Unable to move, Jess became increasingly bed bound and had to be turned manually every four hours. Unable to eat, she began to be tube fed. Unable to swallow, she had her saliva suctioned several times an hour. Day and night, her family structured their lives around hers, even with the arrival of her younger brother.

“You are only going to have her till she is three. She is not going to walk. She is not going to talk. She is not going to sit up.”

Ariel was born into a world where his sister’s needs sometimes overshadowed his own because her life depended on it. “In the early days,” says Debbie, “he definitely missed out on things and it was always Jess. And I always (put) longer hours into Jess in the early days and he wanted Mum and he couldn’t have Mum.” She says this kindly but also matter-of-factly because there is no space for regret in this family’s always alert lives.

“Someone is always up, someone is always awake,” says Ariel, who doesn’t recall his home ever being completely still. Around the clock, someone – his parents at first and then, with help from the National Disability Insurance Scheme, one of a group of dedicated workers – has been with his sister for as long as he can remember.

“Every house we have lived in there has always been one light on, no matter what,” Ariel says. He is 25 now, a confident young man who has just trained as a strength and conditioning coach and who is dedicating his career to helping people with disabilities become stronger, his own childhood having been shaped by what he describes as his non-traditional home life.

“I was very attention-seeking, misbehaving in school,” he says. “I wouldn’t say I was rebellious but I definitely acted up and was maybe on the naughtier scale.”

He remembers his parents tag-teaming to care for his sister over many nights. Later, while his schoolmates travelled widely with their families, his rare holidays were spent mostly at a children’s hospice on Sydney Harbour where he could play with the siblings of other young patients.

Yet, like his mother, he speaks without bitterness of his family’s circumstances and the impact on his upbringing. “If my parents are caught up getting the exact amount of medication my sister needs, that’s a little more important than focusing on if I am doing my homework. My parents applied what they could given the circumstances we are in.”

Those circumstances remained mostly precarious, because even as she surpassed so many expectations, the question of Jess’s life expectancy hovered. “We used to worry about what would happen next week or next year,” Earl says, “because you were expecting the worst to happen. And then we would just think about today. And hopefully today will be the same as yesterday.” Somehow, amid that mix of worry and weariness, their lives assumed a sort of rhythm. But even that was not guaranteed.

In 2019 Ariel contracted meningococcal B meningitis, a life-threatening inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. He spent five days unconscious in intensive care, almost died, and left hospital weeks later having lost more than 20kg.

The following year, the arrival of the pandemic affected the household even more than most. Staff were often absent as close contacts of Covid cases, leaving Debbie to cover hours-long shifts, often overnight, when she could not leave her daughter’s bedside. Ariel, who worked in a fruit shop, moved out temporarily, concerned about passing on the virus to his severely immune-compromised sister.

More recently, when it seemed impossible for Jess’s list of maladies to expand further, she was diagnosed with precancerous breast tumours. The news so shattered Debbie that she still won’t verbalise her concerns, leaving it to her husband to explain that an operation, which might happen in other circumstances, has been deemed too risky for their daughter, who instead is likely to be only monitored with further scans.

“It’s part of our life where you’re a square peg in a round hole,” Earl says. “Jess has got obstacles in every part of her life and we just fight our way through.”

Canavan disease is so rare that, even though it has been a focus of their lives for decades, Jess’s family still has no idea of its spread in Australia, as the tiny numbers are not published. “There might be one or two others but I just don’t know,” Earl says. In the past 33 years he has met only two Australians whose family members have the disease and knows of perhaps six others nationally. That rarity, combined with the medical risks associated with the disease, has led Jess and her family to this carefully orchestrated world, with its choreographed routines and minimal exposure to others.

“We have to really stage-manage her life,” says Earl, who rarely has gone out with his wife for most of their marriage, preferring that at least one of them is available as back-up to Jess’s support staff. Their approximation of a date night is watching Netflix late into the evening in the lounge room.

As the sole income earner, Earl is sometimes away from his home office. But Debbie has remained largely tied to their house for years, overseeing staff when she is not caring for Jess or training new support workers, with little down time. She does not drive and since Covid, to minimise the risk of passing on any infection to her daughter, she has stopped taking public transport. She only recently sat in a cinema for the first time in years. For Jess’s sake, she wears a mask in the supermarket and rarely travels farther than a few kilometres.

Being here so often has made her relish the few times she has been able to be away in decades: the handful of days she was given at a retreat in Byron Bay (“oh my gosh I could breathe”) and a wedding in Bali. For her 60th birthday four years ago she spent a day in the Hunter Valley courtesy of the nurses who have become her friends. This summer, for the first time in years, she and Earl will be away at the same time – for one night – to attend a family wedding.

Like most parents, Debbie has a bucket list, although hers seems largely hidden. Top spot is jumping out of a plane. She also would like to travel and hankered for a long time to see India. “But I’ve stopped that. I don’t want to go to India now. Maybe one time,” she says in an on-again, off-again snippet that hints at a tomorrow she dares not imagine.

“People think: ‘You don’t take holidays, how could you do that?’ ” says Earl, who also has largely obscured thoughts of what might have been. “But if they are thrown into it, many would do the same as we are doing.”

At the centre of all that they do, and all that they have sacrificed, is an adult daughter who is swept up in a childhood disease. Jess is 33 but looks like a girl, with butterfly clips in her hair and orange nailpolish on her small soft hands.

“She’s a beautiful soul,” her adoring mother says. “She’s got a happy disposition. She’s got a sense of humour. She’s gentle. She brings out the best in me. She has made me a better person.”

From Jess’s motorised bed, every aspect of her life is co-ordinated around her: she is medicated late each morning to stop seizures and moved every four hours so she doesn’t develop pressure sores. Since Covid, she also has lived with a perspex half box near the head of her bed, a further layer to ward off anything that may harm her.

To access her these days, visitors first need to pass a combined Covid and flu test. To approach her room, everyone is now masked. The layers of precautions that keep her alive are never-ending and they come at considerable cost. “Nowadays it’s only the people that come into our house that would know (Jess),” her father says. “People can drive past on the street and have no idea, other than seeing a disability spot outside.”

Neither would they know of the unexpected paths that have emerged from this home in the process of raising Jess; many of them are far from bleak. For more than 20 years, for example, Earl has been doggedly fundraising for a collection of rare neurodegenerative diseases, including Canavan, which are known collectively as leukodystrophy. He also has established two businesses to help other families: providing home care for people with disabilities and helping others to find supported independent living.

“It’s because of Jess that I am involved in this sector,” he says proudly. “She’s a teacher behind closed doors that no one knows exists. From her bed she has given us lessons in life.”

This is not the life anyone imagined. But no one who loves Jess is complaining. “We don’t ever really talk about what’s going to happen after and we don’t really want to. We’re just enjoying her now,” says Debbie, who still delights in squeezing a plastic rubber chicken or making animal sounds or stomping animatedly so her daughter might laugh. “We make it as happy as we can for her.”

Or as Earl says: “Our benchmarks are really, has she smiled today? And just about every day there’s smiles.”

Appreciation is also key for their son, Ariel. “Jess is very special, unique. We wouldn’t be where we are without her. She has given us a whole set of skills. Jess has taught me to be patient. And my parents have shown this too, seeing everything glass half-full,” he says with a smile. “Some people think that the whole world is against them. But we don’t view it like that at all. The total opposite.

“It’s a blessing, if anything. I guess for me and how I have grown up, life is a beautiful thing.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout