Bill Henson on why art and politics don’t mix (and if they do, it’s probably propaganda)

Bill Henson, one of Australia’s most decorated living artists, says we’ve forgotten about beauty in art, in favour of ‘ticking boxes about ... post-colonial pushback, DEI, BLM, LGBTQ’.

“I’m not interested in anything anymore,” Bill Henson says when I walk into his studio on a crisp April afternoon. He’s rugged up in a blue beanie, a navy V-neck sweater with brown elbow patches, chinos and his signature RM Williams boots. He has a scarf wrapped around his neck and tucked into his woollen jumper. It’s not that cold; it’s April. “Nothing, I tell you. Except beauty.”

Luckily, for Bill Henson there is no lack of beauty in his life. This is my fourth visit to his home in Melbourne’s Northcote, where he and his partner, the painter Louise Hearman, keep their studios. But time has done nothing to dim the Stendhal syndrome that hit me the first time I visited. Walking up the narrow cobblestone path, past the ivy-festooned walls of the former horse-stable-turned-mechanic’s-workshop, I had little idea what I was walking into. I want to say that when Henson appeared, swinging a key and opening the large iron gate, I felt like Charles Ryder laying eyes on Brideshead for the first time. But it was more like tripping over and landing face-first in a Fellini film.

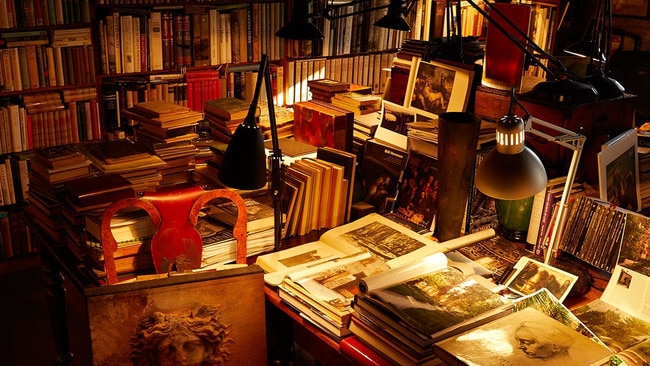

I’m here today to see the works that will appear in Henson’s upcoming show at Roslyn Oxley9. It’s the first time he has exhibited framed works in more than 20 shows with the renowned Sydney gallery. Henson’s vast, two-storey studio is separated from Hearman’s by a skinny staircase that leads to the mezzanine where the couple live and where Henson keeps his library.

Several thousand art books line one two-storey wall (it’s a fraction of his collection). It’s filled with Henson’s ephemera, including an 1870s Neapolitan chair, louche in the middle of the sprawling workshop where thousands of his photographs are arranged in racks. Most are partially obscured by a ghostly diaphanous plastic which he whips off with dramatic flair when the urge is upon him. A Renaissance-era marble replica of a 1st-century Roman torso hangs on a wall beside an arrangement of 18th-century French furniture.

Time and space slip away here. Henson is in the studio every day, alone.

He has never had assistants, although thousands have pleaded to work with him. “It is imperative that people try to make their own work rather than farming it out to other people for production,” he tells me. (A fine art photographer of Henson’s stature would usually work with a team composed of a studio manager, and assistants and technicians to help with lighting, camera setup, editing and archiving.) “To a significant extent you learn what the work is about through the business of trying to make it … it’s through the sheer process of trying to bring this vision from the world of the imagination into the physical world where someone can see it, smell it, touch it. It’s an entirely unreasonable arc. It is the process by which an artist comes to understand what their work is about.”

Over the course of a year I’ve spent many hours talking to Henson in the studio and library, forgetting I’m just metres from Northcote’s trendy cafes and bars. It feels more like a salon where a Henry James character might cough into a rag. Henson is mad for lamps, and both his library and studio are lit up by scores of them, casting the exact mix of light and shadow that makes a Henson photograph so uniquely his. Being in his studio is like stepping into one of his pictures, and his pictures feel like stepping into the dark shadows of Caravaggio; I’m caught in some kind of chiaroscuro loop.

Up the back of the studio are hulking antique chests bearing a lifetime of work, including hundreds of journals going back to Henson’s earliest scribbles – he was filling books with intricate pencil drawings of ancient Egyptian tombs as soon as he could write. During one interview he has a tussle with one of his antique lamps so we can better see what’s inside the drawers. We find the oldest of all the journals and I notice that the six-year-old who would grow up to be one of Australia’s greatest living artists had the prescience to write “Volume One” on his very first scrapbook.

“I sucked in ancient Egypt like a ratbag at the age of 10 and Rembrandt at around 11 or 12,” he says, wiping the dust off the crumbling book. “I had a tremendous appetite and a sensibility for things I didn’t fully understand. I found it utterly compelling. Nothing’s changed.”

Growing up in the then semi-rural Melbourne suburb of Glen Waverley, Henson drew and painted compulsively. While the neighbourhood boys played footy and “bashed each other with sticks while listening to Acca Dacca”, Henson spent his days lying in the tall grass watching as the boggy marshes of Dandenong Creek turned into the etchings of Rembrandt.

By age ten he was working at a milk bar and spending all his money on books. Up in his library, where one wall is dominated by a glass-doored Victorian bookcase housing rare and first editions, and every surface is covered in books lit up by a fleet of industrial anglepoise lamps, Henson opens a book on ancient Egypt. Billy Henson, it says on the inside, 25 shillings, 1965. Two others, Anatomy for the Artist and Greek Architecture, were bought for 35 shillings in 1966. By 1968 Billy had dropped the “y” and bought his first book on Rembrandt. Next, he moved on to Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.

He maintains that as a kid he did regular things too, like skinny-dipping with the boys who lived on the apple orchard next door, crying and laughing, walking home caked in mud, the moon rising … but his boyhood was mainly spent with his face inside books. And not much has changed.

When I first met Henson a year ago itwas in the grand dining room of Carthona, a neo-Gothic pile on Sydney Harbour belonging to his art dealers, Roslyn and Tony Oxley.

“Bill’s works are, and always have been, extraordinary,” Roslyn Oxley tells me. “When you’re in the art world, or following the art world, you get involved, emotionally. And I think Bill’s work is quite emotional. We get, even now, big, big crowds at his openings.”

Oxley first met Henson in a hotel elevator in New York. The story goes that the gallerist had him pinned to the wall, demanding he join her stable of artists by the time they reached the fifth floor. She has exhibited him since 1990, including the 2008 show that became the centre of a media firestorm when the gallery was raided by police (around 20 works were seized following public complaints about the use of a naked 13-year-old model on the invitation for the exhibition. Henson never faced charges). Kevin Rudd, then prime minister, called the work “absolutely revolting” and lacking in “any artistic merit”. Malcolm Turnbull, who owns a few Hensons, came to his defence. What did the poet Langbridge say? Two men look out through prison bars. One sees the mud, and one sees the stars. One result of the furore was that it inoculated Henson against the shifting morality of the art world.

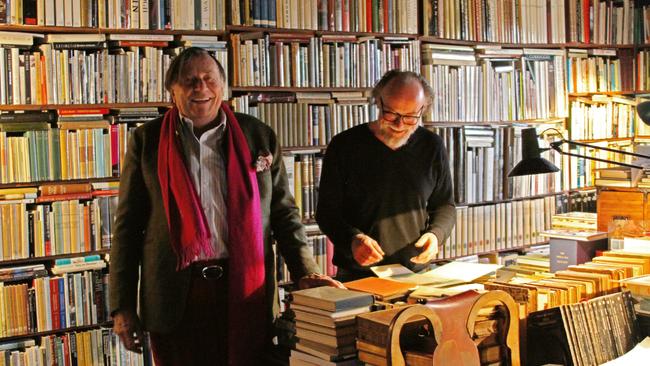

As artists and their buyers mingled over Thai chicken curry and chugged down chardonnay at Carthona, Henson and I got talking about libraries – the way they reflect the intellectual and emotional life of the people who own them, like a cumulative self-portrait while they are alive and a time capsule once they are gone. This got him started on the author Elias Canetti (it doesn’t take much to get Henson started on Canetti) and the final scene of the novel Auto-da-Fé, in which the main character sets himself and his library on fire. “There’s a link between madness and libraries,” Henson told me. “You should come see mine.”

Of course I already knew a little about his library – it was described as “the most interesting and scholarly private library in the southern hemisphere” by his dear late friend Barry Humphries.

“Our literary tastes unfortunately converge here and there, and not seldom if I contact an antiquarian bookseller in New York or Edinburgh and try to order a rare work by, say, Norman Douglas or Forrest Reid, I will be told that, regretfully, the book I had wanted has already been snapped up by a collector in Melbourne,” Humphries wrote in 2015. “It is surprising that our friendship has survived such affronts.” Such was their constant (though good-humoured) competition for the rare books they both coveted that the antiquarian bookseller Kay Craddock used to keep two shelves marked BH1 and BH2.

In the wake of the 2008 controversy, Humphries mounted a vociferous defence of his friend’s work, writing in The Australian: “I have heard Henson both dismissed and extolled as an ‘erotic’ photographer, which is woefully remote from the truth. His recurring subjects, nude or partially clad, are a far cry from the strutting mannequins with whips, black PVC girdles and stilettos that are the clichés of commercial eroticism.

“His figures, caught seemingly in the blue flash of headlights or refracting the illumination of some outer suburban wasteland, have such poignancy and grace that it is difficult to believe they could be perceived as offensive.”

When it comes to collecting books, Henson has a particular fetish. “Having a book that belonged to someone else, which has their signature and the signature of whoever gave it to them a century before, is a direct physical connection to the past, in a way,” he says as he shows me around the library. “People may say, ‘Just give me the paperback of Flaubert, I’ll read that’. Of course, that has the content, but form and content need to balance. And in an ideal world, form and content are indivisible. There’s a certain gravity that comes from holding Lord Byron’s copy of The Vampyre written in Villa Diodati the night Mary Shelley whipped up Frankenstein. Objects are the physical evidence of times past. They bear the traces and the imprints of history in terms of wear and tear – the patina, if you will. Sometimes we know about certain books but we are not ready for them. Some books wait years until you’re ready for them.”

He shows me his copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray signed by the author, Oscar Wilde, and we talk about the lovers of Nancy Cunard (he has her letters), the films of Fassbinder, the plays of Thomas Bernhard (he makes me promise to read them when he hears I have Viennese heritage), and look through his shelves filled with Thomas Mann and Knut Hamsun. We will talk about Plato, Mahler, Sofia Coppola, and back to Canetti (always). He shows me his copy of Oskar Kokoschka’s The Dreaming Youths – published in 1907 and known as the first great Expressionist book. Henson says only four of these hand-bound editions survived the Second World War. The Museum of Modern Art in New York has a copy, as does The National Gallery of Victoria.

We argue, politely, about muses when I try to protest about the male gaze. “The muse gives an artist a tremendous gift,” he says. “It’s a critically important relationship and you never know where it’s taking you. When you work with [models] for years, as I do, it’s life-changing. Indeed, I’m in awe of the force of this relationship on my journey. To reduce it to a political power dynamic is to miss the profound significance of the relationship.”

He places Lord Byron’s copy of The Vampyre in my hands. “I draw such immense energy and pleasure from all of the beauty that I see in Western culture,” he says.

Art critic John McDonald first met Henson in Venice in the early ’90s. They bonded over Zemlinsky string quartets, which they were both listening to at the time. “Every conversation we have veers between books and art and film and music – it goes all over the place,” McDonald says. “I’ve met thousands of artists over the years and he is, without doubt, one of the most intellectual – but he’s also someone with deep emotional engagement. His sources of inspiration come from many different places. He’s not just the guy who goes and photographs naked teens in the bush. He has broad-ranging interests; his interest in music, for instance, feeds into his interest in art and photography.”

Henson’s interest in music borders on the obsessive; he talks about it more than he talks about photography. On one visit he leans in and tells me, “There are tens of thousands of people around the world who can play the piano really, really well. But there are only a handful of people who can play the piano and make you feel like you’re in a thunderstorm and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

“Bill is a bit of an outsider within the art world,” McDonald says. “On one hand, he’s a very successful artist. Everything that one would hope to do as an Australian artist, he’s done. He’s been considered to be a big, fashionable, collectible artist for a long time. But for all of that, he still feels like someone who is not quite in the club.”

It’s quite an extraordinary notion, given Henson’s work is held by every major institution in the country and many internationally, including the Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris, London’s Tate Collection and the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York. He represented Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1995, and last year was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) acknowledging his “distinguished service to the visual arts as a photographer, and to the promotion of Australian culture”. His first solo exhibition was held at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1975. He was 19 years old.

Says McDonald: “He does his own thing. He doesn’t hang out with all the other artists who are supposed to be cool. He and Louise make their own friends, who can be a very idiosyncratic bunch of people. They have their own interests. They don’t follow the trends. They don’t attach themselves to whatever others are worried about or whatever else the curators are obsessed with. His ideas remain the same.”

Those ideas were tested recently when the mainstream Australian art world leapt to the defence of Khaled Sabsabi and Michael Dagostino, who’d been chosen to represent Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale, after Creative Australia stripped them of the honour. The decision came after concerns were raised about historic works from Sabsabi’s oeuvre – You (2007) and Thank You Very Much (2006), the former depicting a glowing Hassan Nasrallah, the late leader of terrorist organisation Hezbollah, the latter an 18-second video piece using footage of the September 11 atrocities. The artists decried the move as censorship (while not acknowledging that Sabsabi had signed a petition calling for the boycott and censorship of Ruth Patir, the Israeli representative at the 2024 Venice Biennale) and drafted a petition that, among other things, called for their reinstatement. The petition was signed by 27 artists who had previously represented Australia at Venice, and appeared in a two-page ad in The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald. Henson was one of only two former representatives of Australia at Venice who did not sign the petition. I ask him: Why didn’t he sign it?

“Where a public letter of protest from the artistic community is concerned, I wouldn’t grace the political types with a reply,” comes the answer.

As for the whole affair, “this is a storm in a teacup and was never about art and censorship”, Henson says. “It was only about political expediency. With a federal election imminent the incumbent party is busy trying to bring their jumbo in to land and all of a sudden there’s a group of artists sitting on the runway. Politicians will always be happy to spend a couple of artists to gain a little bit of moral high ground.”

He has little time for identity politics, and especially not when discussing art. “The problem, as I see it, is that politics has replaced aesthetics as the overarching discourse,” he says. “What is it that makes one brushstroke compelling and another brushstroke of no consequence? Aesthetics. You can look at Goya’s Disasters Of War and indeed they’re great pictures but no one would have ever looked at them if they weren’t great pictures. They happen to be about the horrors that were unfolding at that time, but the reason people look at them now is that they are mesmerising.

“Indeed, they are the opposite to ‘people using their practice to interrogate their issues’. As people go down their lists ticking boxes about this or that – about post-colonial push-back, DEI, BLM, LGBTQI – it’s essentially political. And if it’s politics it probably isn’t art, but it certainly is propaganda. Of course, politics is the lowest rung on art’s ladder to heaven, whatever that may be for each person.”

All of this is searingly relevant when you consider we are living in the most political climate for the Australian arts in decades. A schism has emerged, particularly in the Melbourne scene, in the 18 months since the horrific October 7 attacks in Israel and the devastating war in Gaza that has followed. NAVA, Australia’s peak body for the visual arts, set the tone in the days after October 7, when more Jews were slaughtered than on any single day since the Holocaust, sending out an open letter stating that the massacre could “not be decontextualised”. Since then Jewish people have been removed from boards, arts festivals linked to Jewish donors boycotted, and antisemitic rhetoric regularly spewed online.

It’s clear that Henson, who reveres Jewish artists, writers and thinkers (Canetti is one of a great many) is perturbed by these developments, not least because of the value Jewish people place on the arts. “To paraphrase Barry Humphries’ alter ego Sir Leslie Colin Patterson, without the poofters and the Jews there would be no contemporary art in Australia,” he says.

I ask him why the Melbourne art world appears to be so laden with what The Australian’s art critic Christopher Allen described as “the anti-Jewish mob”, and he answers by summing up the art world he’s both inside and outside of: “Look, there’s a generous sprinkling of highly intelligent and sensitive people with a good moral compass,” Henson explains. “However, there are elements within the visual arts who are intent on creating division and polarisation. It’s basically ‘divide and rule’, and it’s a very old game, that one.”

On the crisp (if not necessarily cold) Aprilday when I enter Henson’s studio, he has set up a photograph for me to see. It’s one of ten works that will hang in the upcoming show with Oxley, which includes historic works that have never been exhibited before. It’s classic Henson – a mix of disembodied unclothed figures (male and female), architecture, and stirring landscapes. He says he didn’t hear me buzz because he was listening to Rachmaninoff’s Isle of the Dead, the piece of music inspired by the Swiss artist Arnold Böcklin’s painting of a shrouded figure being rowed to a desolate island full of cypress trees. There’s a ladder at one end of Henson’s studio leading to a small turret where he keeps thousands of records and CDs and a state-of-the-art sound system that floods the cavernous space with the music that is so integral to his work.

“I should play it for you,” he says.

He puts the music on at an ungodly volume. I accept that my recorder won’t pick up anything he says. It’s worth it, though, as I stand in front of the photograph of two figures locked in an embrace. I don’t want to reach for the word “tender”, as so many writers have before when talking about Henson’s work. But I do. Not only because I can see it in the glint of an eye, in the fall of a hand, in the drape of their bodies, but because, over our interviews, I’ve seen it in the artist too. I’ve absorbed the way he speaks about his mother, whose garden he transplanted after her death in 2016, turning the former carpark out the back of his home into the arcadia that he lovingly waters and in which he sits every day. The tenderness is palpable when he speaks about his and Hearman’s beloved but departed Staffordshire terrier, Mr Pigs, whom he would carry up the narrow staircase at the end of every day, once the dog became too aged to take the stairs himself. I’ve seen it between Henson and Hearman, who met in 1981 while Henson was teaching at the Victorian College of the Arts (Hearman won the 2014 Moran Portrait Prize for her portrait of Henson). And the tenderness comes out when he talks about his models, most of whom he has worked with for decades. There’s a lift in the music and I understand why he says it’s the perfect piece to accompany the image – it encapsulates what Canetti (yes, Canetti again) describes in Auto-da-Fé as sehnsucht, the German term for deep longing or yearning.

“Are they standing up or lying down?” I ask him about the figures.

“Exactly,” he answers.

Henson turns 70 later this year, and his appetite and drive are stronger than ever. “More than at any time in my life I feel overwhelmingly that I haven’t even started making pictures yet,” he says. I have discovered over the course of our new-ish friendship that he is not dark and brooding, as one might assume. He is eloquent and erudite but also jaunty, mischievous, and prone to theatrics and impersonations. He does a great one of his French publisher, who he describes as a Clouseau-esque character with madcap ideas – “Let’s make your next book out of glass!” – and another of Humphries. His speech is peppered with expletives and he often makes fun of himself. He’s partial to Italian whites and wields a wine glass with insouciance. Occasionally, when his hands need to do the talking, he rests a full glass on his lap. He doesn’t spill a drop.

“Bill is someone who wants to make the viewer slow down and really just enter into the world of the photo,” McDonald says. “Often it’s the case, if it’s a figure, that he wants us to feel the proximity of another human being … often someone who’s vulnerable, someone who seems alone in the world. He wants us to be back inside our own little core of humanity.”

I can attest to that. Six months ago, during another of our meetings, Henson had disappeared into the labyrinth of his racks and emerged with a photograph. It was midnight. He placed the picture of a reclining naked figure in front of me. “Like an oily hunk of marble hauled out of the sea,” he said. Outside there was a lunar eclipse. Inside, Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata flooded the studio. I looked at the picture, full of sadness, longing, tenderness and grace. It felt like I was in a thunderstorm and there was nothing I could do about it.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout