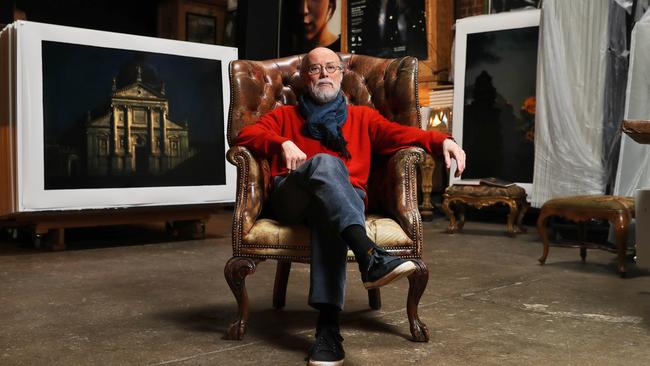

Going home: Bill Henson

Photographer Bill Henson returns to the Melbourne suburb he captured on film during his youth.

have known Bill Henson for the better part of 40 years but one of the things we have in common stretches back further than that: we both grew up, as did poet Peter Rose, in the outer Melbourne suburb of Glen Waverley. We’re back there now because the Monash Gallery of Art is opening a show in nearby Wheeler’s Hill that juxtaposes Henson’s photos of this long-ago suburban seedplot of so many baby boomers made in the mid-1980s with photographs of the area made more recently.

The earlier pictures feature suburban rooftops, luminescently framed with the sublimity of the architecture of ancient Egypt, a childhood passion of the photographer; the latter capture the same stretch of territory but are laden with a longer and deeper sense of memory, where locality is now a presence, an evocation rather than a signpost. Here in the deep-dark of the Monash Gallery of Art with the Hensons coming at you like apparitions of light and remembrance, everyone in attendance at the gallery — including Julian Burnside QC — looks like a revenant of Glen Waverley lost.

Bill Henson speaks illuminatingly about the paradoxical nature and the necessity of the Glen Waverley project, which was commissioned by the MGA and which is grounded on the radical unlikelihood of attempting to photograph a world that no longer exists, and that was ceasing to exist more than 50 years ago.

“Ah, the impossibility of things in art,” Henson says of the exhibition and its accompanying publication, The Light Fades But the Gods Remain. “It’s one of those things that draws you in because there’s a gathering sense of disbelief as you become familiar with the work.

“In the late 70s, when I first saw Rembrandt at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, it was a stormy landscape done about 1637 and it was as though the way the sun hitting the trees from the 1630s was still hitting the trees then. And when the same picture was shown at the National Gallery of Victoria 20 years later, I was amazed that the sun that was shining on the trees was still shining on the trees as it had been in 1637. It was as if it was eternally in the present. And that’s the thing with photography.”

For more than four decades Henson has been one of the country’s leading photographers. His work — famously rendered in painterly chiaroscuro — is in the collections of every major gallery around the country and his photographs command astronomical figures at auction.

But Henson is more than a photographer. He’s a thinker. A philosopher. Always looking beyond the frame.

Henson admits that nearly all the thinking he’s interested in inclines towards the magical, and when you listen to him you get used to the idea of images resisting and coalescing as he feels his way into a subject. How can he dramatise the memory of a lost world, the ghostly presence of a physical world, all those disused apple orchards, all that fading away of former bush, without showing it? “That’s a bit like that trajectory of the imagination into the physical world. And there’s the unlikeliness of that: how has it been possible?”

It was one of the medieval saints, wasn’t it, who said he believed because something was impossible. But the faith to Henson is as real as a bodily memory, a sensation older than sense.

“There’s that sense in which your body knows the landscape before you do,” he says. “Your body is reading the landscape before you even consider it.”

Continues Henson: “It’s the sense of the spirit of place, the genius loci, and what it sparks and the way we carry our childhoods inside us for the rest of our lives.”

The Light Fades But the Gods Remain is, in a broad sense, a story not just about Melbourne. It is a story about Australia. Says MGA director Anouska Phizacklea: “As the majority of Australians grow up in suburbia, the new body of work speaks to a shared history, harking back to childhood, and capturing something of Australia’s national identity, our sense of place, belonging and home.”

Of that personal geography, Henson cites one of his favourite writers, Gerald Murnane, then indicates his own heart’s country. “It’s so deep in a way it’s invisible to us,” he says. “It regulates so much in our lives. Gerald is stuck with his landscape investigation — that sense of the plain with the grass going off inland — whereas for me it’s that gentle folding landscape that leads up towards the Dandenongs. That’s where my heart wants to go.”

There is a pleasing aesthetic in his art but Henson muses that beauty can’t be loved — it can only be longed for, even though he’ll say a moment later that the creation of a great work of art such as Mozart’s The Magic Flute or Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son necessitate the artist being in love.

He qualifies the notion of love —— via one of his heroes, author Elias Canetti —— and says that what he’s talking about is not so much love as longing. He cites Nietzsche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra on the intelligence of the body and then he’s off again attempting to crack the nut of how one represents, how one recovers, the definitionally irrecoverable. How to recapture Glen Waverley.

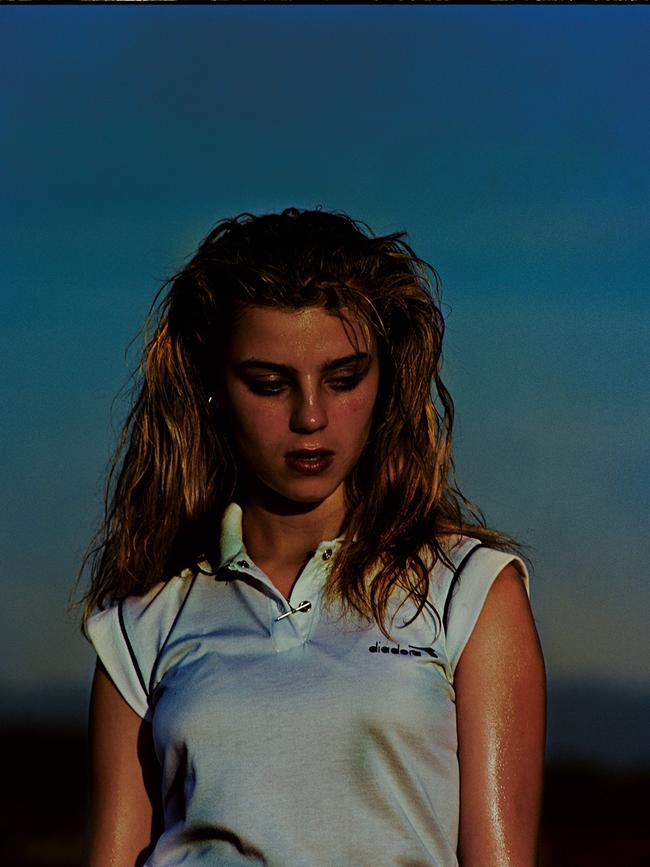

The writer David Malouf, who has a deep fascination for Henson’s work, was a source of early inspiration for Untitled 1985-86, known colloquially as the Suburban Series. “What I was interested in,” he says, “was what Malouf called dreamscapes. And so because of my love of Egyptology, as a kid I used that in the 80s pictures. At the same time I wandered about the wilderness of the Dandenong Creek and the reading about Tutankhamun was strangely relevant. What Malouf said was that it was as if the Egyptian ruins and the suburban landscape were being seen at an equal distance or an equal closeness.”

The mid-80s pictures of Glen Waverley have a rich, haunting counterpoint with the images of the great Egyptian monuments, which have always been to Henson the closest possible vista of divinity. The new series — the work of a remembrancer in his 60s — is like an exercise in the kind of symbolism that denies itself the satisfaction of asserting its own subject. As poet Mallarme said: “Paint not the thing but the effect of the thing in the mind.”

“With this new group of pictures,” Henson says, “perhaps there’s even less of the physical or the visual. It’s not just that it slips away from thought, it slips away from the eye. You have a great uncertainty about the nature of the physical space because so much of it is too close or too far from the focal plane of the camera.”

He glides around this subject, ruminatively. He is the first to acknowledge the radical difference between the two series.

He is tinkering with a created world that could almost be abstract, almost be sheerly and mysteriously physical. “It’s almost as though the detail is incidental,” he says.

“You know the physical nature of the tree, the dam, the house, the freeway, or whatever it is. I feel increasingly, though, as if it could be anything. It’s almost as though you have to leave me out and that’s why I’m ever more elusive or ambiguous about where the pictures were taken exactly. Though I wanted to say pointedly that these pictures had been made in the last two years because Glen Waverley doesn’t look like that anymore.”

He knows where this is leading. And where else could it lead?

“All these things are very much self-portraits: the wilderness, the blackberry bushes, the decayed pine trees. It’s all a bit of a self-portrait in the sense of Flaubert: ‘I am Madame Bovary.’ What are these pictures about? Well, what else could they be about?” he says.

The thing about Bill Henson is that he never errs into solipsism or egotistical sublimity. Apart from anything else he cares too much, in the most down-to-earth way, about the world he is refracting and reflecting and turning into an inscrutable image of his own sensibility. When I suggest to the man who lives in the darkened grandeur of a huge warehouse in Melbourne’s Northcote — with its vast bookcases of every kind of book, its huge array of CDs, its towering ransom-costing palm trees in the garden — that town planners were simply wrong when they thought the centre of the metropolitan area would shift to Waverley, he sharply distinguishes himself.

“I never felt the disdain of the Lamborghini socialist who hated to be seen as a product of the suburbs when we were, at least in the 70s when this snobbery was most prevalent, the most egalitarian society on earth and the most suburban. I found the landscape incredibly beautiful, even if in its particulars I could see the mundane nature of what was occurring. There was the infrastructure and the architecture, but there was also the ground underneath and the added excitement that trees gave to the topography.”

One of the paradoxes of Henson, an artist’s artist, is that although he has such a lack of affinity for political attitudes, he can sound like starkest green about the environment, more so because he is so unashamed of his suburban lineage.

“We’re really doing a fascist revision on ourselves. You know, it’s clinical psychology. It fractures the continuity — not just of one’s mind — but in the end everyone becomes a kind of refugee and all of these old things, all the trees and plants and gardens we’re getting rid of, the loss of these things, and the loss starts to plague people because of the privation, the loss to the public imagination.

“No one’s at home any more in their lives. Everything’s moved around. You keep moving people around and they become more vulnerable. They have no sense of belonging, no knowledge of their own circumstances.”

In practice when Henson sees some rare or beautiful plant in an old garden belonging to a house that is to be demolished he’ll hop the fence to rescue the shrub, he says.

Then, as if a cloud has passed, we’re back to the domain of art.

“I would say you become the thing you love,” he says. He repeats it for emphasis: “You become the thing you love.”

“So I’ve tried to make the portrait, a portrait of —” he stops and laughs. “Well, of the subconscious. But so that empathy, sympathetic disposition or relationship, is created in the world around you. But it’s a kind of marginalising of the self in the process. I want to say, ‘Don’t say I was there.’ ”

This search for an art of impersonality can lead, as poet Kenneth Rexroth said of TS Eliot, to indiscretions that would shame the analyst’s couch. But Henson is alive to it as he proceeds to rage against society’s loss of its trees.

“I feel it hugely, the loss of the old trees, because they’re probably further down in our sensibilities, but they always existed not just as a symbol but as a fact, as a nurturing and reassuring thing,” he says. “That accelerates detachment from even the natural features of suburbia. And that’s incredibly deleterious. There’s a great tragedy unfolding which we’re visiting on ourselves.”

But it’s all a unity to Henson. Now he’s back speaking about the parallels between his suburban roots and the world of imagination he drank, like an elixir, from art and literature.

“I remember wandering around Dandenong Creek,” he says. “And the flat boggy landscape where the creek melted into those long horizontal marsh landscapes that Rembrandt painted. And it all became one, of course. It all blended in my mind.”

He talks of getting one of British author Leonard Cottrell’s Egypt books when he was 10. Written in pencil on the opening page is a scrawl: Billy Henson, 1965: beneath the price — 2/6, in the pre-decimal currency.

He gets the same thrill today from seeing in his bookshelf his folio of Michelangelo’s drawings as he did the day he bought it — November 28, 1970. As a boy, he would catch the train from Glen Waverley, then sit all afternoon in Cheshire’s old basement bookshop, looking at the art books for hour after hour.

Again he connects this with the representation of the world he has lost, which is imaginatively, perennially, found.

“It’s interesting looking at these things,” he says, “and then being out in the suburban landscape, that rural suburban landscape. There wasn’t a break between these things: they’re continuous with one’s interior life.” But he sticks to an artistic credo of restraint, of removal.

He talks about how in all the forms of art he loves — words in books; shops in films — they tend to take on the status of objects. He thinks this is true of the carved head on the mantelpiece in Bunuel’s 1962 surrealist film The Exterminating Angel and he thinks it’s true of “the rollercoaster ride of madness where every word is of complete significance in a novel like Old Masters”, by great Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard.

You can tell how far this Glen Waverley boy — who played in the apple orchards, in the dust, and in the bush — has come. And you can tell how much he has remained true to the plain, at once entirely imaginary and sharply real, which, forever edging out of the picture, he has attempted to memorialise with every atom of sensibility he can muster.

The Light Fades But the Gods Remain is at the Monash Gallery of Art until September 29. Henson’s book, co-published by Monash Gallery of Art and Thames & Hudson Australia, is released on September 23 (165pp, $100, HB); a premium edition with signed slipcase is available for $150 from the MGA shop.