Australians changing the world in the fields of sustainability, food technology and dining

Methane-eating seaweed, avocados grown in a lab, and the march of the flat white towards World Domination. In the world of sustainability, food technology and dining, these Aussies are making a global impact. | FULL LIST

Just a few years ago Sam Elsom, a former high-end fashion designer, was busying shaping clothes, globetrotting for cotton supplies and raising a family when he accidentally collided with his future.

It was September 2017, and Elsom attended a lecture by renowned environmentalist Tim Flannery. In his speech, Flannery discussed the potential of seaweed to store quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It instantly inspired Elsom. He would farm seaweed and help save the planet.

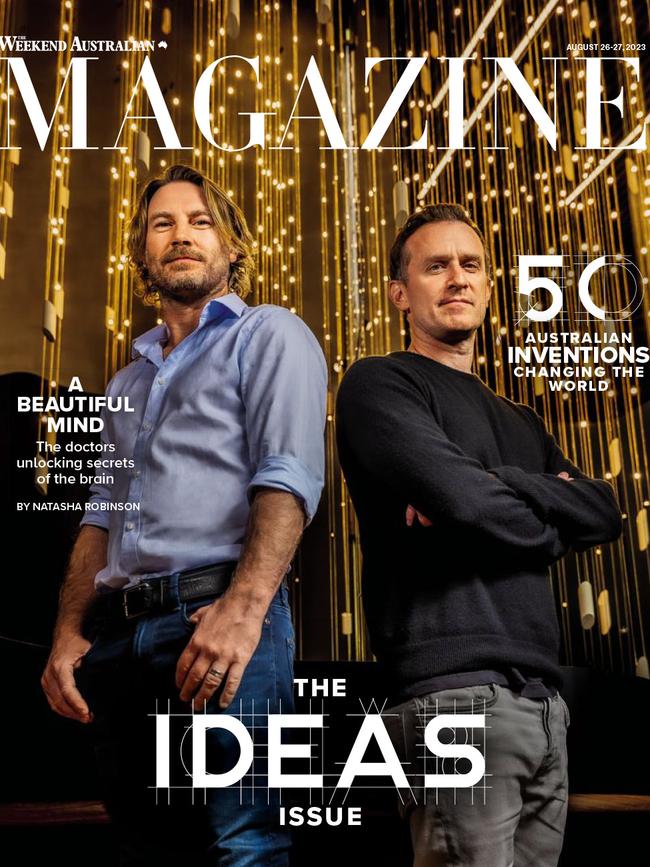

Discover the 50 Australian inventions changing the world in The Weekend Australian Magazine’s Ideas Issue this Saturday.

But there was another twist. Elsom’s commitment coincided with recent research out of the CSIRO and James Cook University in Townsville, north Queensland – that some compounds in seaweed had the ability to dramatically reduce methane production in cows and sheep. They would discover that two species of a particular Australian red seaweed – the Asparagopsis taxiformis (found in warm Queensland waters), and the Asparagopsis armata – (common in the cooler waters of Tasmania) – reduced livestock methane production by up to 90 per cent if added to the animals’ diet.

Given that 11 per cent of Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions came from ruminants (cattle, sheep, goats), Elsom saw an opportunity. He would grow commercial quantities of Asparagopsis and take a significant chunk out of the world’s, greenhouse gas emissions. (The planet’s 1.5 billion cows and 1.1 billion sheep contribute roughly 6 per cent to all global emissions.)

By 2021, Sea Forest had attracted more than $40m in investment funds, and it continues to expand. By late last year it was producing 7000 tonnes of Asparagopsis per year, or enough to feed 300,000 cattle.

Sea Forest is not alone in the seaweed farming industry, which is rapidly developing into a multibillion-dollar global industry. In August 2021, an Australian Seaweed Institute report predicted the domestic industry could potentially generate $1.5bn annually by 2040, while reducing greenhouse emissions by 10 per cent. And that’s all thanks to a native Australian red seaweed, and visionaries like Sea Forest chief executive Elsom. He told The Australian last year: “Australia is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet and there’s a tremendous opportunity to better understand the life of seaweed and its many uses.” – Matthew Condon

The Australian inventions changing the world

Brain powered: control a computer with your thoughts

It was once the realm of science fiction. Now, a brain-computer interface developed by this Aussie team promises to revolutionise and reshape the way we communicate.

Soldier’s best friend: why ‘Bushie’ is a great Aussie invention

Since it entered service the Bushmaster has saved hundreds of Diggers from landmines, IEDs and enemy fire – it’s one of our country’s best industrial innovations. | FULL LIST

Can these engineers disrupt a billion dollar market?

Their microneedle medical patch designed to monitor the efficacy of administered drugs is among the top Australian medical breakthroughs improving human health. | FULL LIST

Heaven sent: two Aussie punks take over Marc Jacobs’ world

When the fashion supremo needed a breath of fresh air he turned to two Australian creatives - Ava Nirui and Elliot Shields. The pair are now among our leading fashion innovators | FULL LIST

How a Tassie seaweed farm can help save world

Methane-eating seaweed, avocados grown in a lab, and the march of the flat white towards World Domination. In the world of sustainability, food technology and dining, these Aussies are making a global impact. | FULL LIST

Man behind the ‘masterpiece nobody should miss’

He is the pioneer of ‘cine-theatre’ whose latest five-star production is headed to the West End and will feature a Hollywood star. Kip Williams leads our list of cultural innovators | FULL LIST

The Aussie company out to send astronauts to the moon

A plan to send a 25-metre tall rocket into orbit from a North Queensland spaceport is just the beginning for Gilmour Space, who lead our list of Australian tech and gadgetry innovations making an impact in 2023.

Australia’s best sustainability and food innovators

Plastics pulped

Two the leading recycling innovations coming out of Australia are making inroads to reducing the amount of global plastic waste. Take Bio-Pak, founded in 2006 with a singular mission – to eradicate harmful plastics and replace them with compostable plant-based materials. Bio-Pak produces everything from plates and cups to straws and napkins. Earlier this year it shipped out a sample of its compostable takeaway coffee cup lids to 15,000 cafes across Australia in an effort to eliminate the ubiquitous polystyrene lids. Its latest invention – hot/cold cup lids made from sugarcane pulp – won an international sustainability award in January, and showcased the company’s green credentials to the world. Then there’s rePlated, and its ambition to eliminate single-use plastic food containers by replacing them with recycled meal boxes that are made – in a world-first innovation – from ocean-bound plastic. Australians consume millions of takeaway meals each day, and rePlated’s pioneering Swap & Wash scheme provides boxes which are used, then cleaned and reused. – Matthew Condon

Vow

Tonight on our menu we have the cultured Japanese quail, or perhaps you’d prefer to try the water buffalo, or the alpaca or maybe something more traditional, yes? The kangaroo? Did I mention these delights have each been grown inside a laboratory? Sit with that for a moment. How does it make you feel? Because sooner, rather than later, Sydney-based start-up Vow could become the first cultivated meat company in the country, inventing and experimenting with meat that is, according to its website “tastier, more nutritious, more functional or more exclusive” than, let’s say, chicken, beef or pork. Its founders George Peppou and Tim Noakesmith operate from a facility in inner-city Alexandria where their team can grow meat from cells-to-plate in about 4-6 weeks. What is this “meat”? Well, it could be anything. It could be an entirely new thing, or it could be meat from an animal we’d never dream of farming. So far, Singapore is the only country in the world to approve the public sale of lab-created meat for human consumption, but Vow is betting on more territories to follow, and they’ll be in prime position to take advantage. This is a company whose tag line is “food that is forged, not farmed” and it is surely on the precipice of an enormous shift in the way the planet considers how to feed its many billions. – Jessica Clement

Harrington Seed Destructor

Put simply, weeds are the arch-enemy of the crop farmer. Weeds reduce a farm’s overall productivity. They are a source of pests and diseases, compete with the crop for nutrients and water and annoyingly, come harvest, their seeds are easily spread by a farmer’s own equipment. For 50 years herbicides have been the most powerful weapon in the weed-battling arsenal but over time those wily invaders have developed a resistance to our chemical weapons. Perplexed by this, Western Australian farmer Ray Harrington, already the inventor of such farming friendly advancements as the Harrington Crutching Cradle, the Harrington Sheep Jetting Race and the Harrington Vee Sheep Handling Machine, turned his mind to the problem and settled on the idea of destroying weed seeds mechanically. His 20-year mission ended with the development of the Harrington Seed Destructor, a piece of farming machinery adapted from the mines. Harrington took the concept of a cage mill, used to reduce rock into powder, and fitted it to a combine harvester. The chaff stream from the harvester is directed into the mill which pulverises the chaff, including the weed seeds that would otherwise have been returned to the field. Et voila! Studies have shown it reduces weeds by close to 100 per cent. It is such a groundbreaking piece of machinery that the Destructor, now under licence to de Bruin Engineering, won a global Edison Award in 2015 and is used around the world. – Jessica Clement

Who Gives A Crap?

The statistics are shocking. Around the world, 289,000 children aged under five die each year from diarrhoeal disease caused by poor sanitation. So 11 years ago, the co-founder of Who Gives A Crap, Simon Griffiths applied himself to finding a better way to get clean water and sanitation into communities who need it. His inventive answer was to create a direct-to-consumer toilet paper company committed to donating 50 per cent of its profits to the cause. To date, Who Gives A Crap, has donated $11m to projects in places like Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea, Cambodia and East Africa. $10m of that money has been raised in the past five years, reflecting a company whose business model of online toilet paper sales reached a new zenith as Covid panic set in and our supermarket aisles were cleared out. – Jessica Clement

Nanollose

Major clothing brands and producers the world over are promising more sustainable practices when it comes to fashion. Spanish powerhouse Zara is one international brand vowing to be 100 per cent sustainable by 2025. One Australian biotechnology firm pioneering new ways to generate cellulose could help them get there. Cellulose is used to manufacture cotton and linen textiles. Traditionally, it is obtained from sources such as cotton, flax and timber. Obviously these require agricultural land, and put an awful lot of pressure on natural resources like water. Well, what if we could create a different source of cellulose? Enter Nanollose, a Western Australian company which has developed a world-first process creating microbial cellulose from industrial organic and agricultural waste, which is then transformed into rayon fibres, which in turn can create a sustainable textile. The process doesn’t involve felling trees or require any land and therefore no irrigation or pesticides. Nanollose’s first product is their Nullarbor tree-free lyocell fibre, which has also been successfully spun into yarn, and then made into a garment (a rather fetching sweater designed by Lee Mathews) using 3D knitting technology. Incredibly, Nullarbor fibre is produced within just 10 to 15 days.

– Jessica Clement

Stelvin cap

We grab the top of a wine bottle. We twist. It cracks open. We pour. We drink. How we take it for granted.

The battle between cork and screw cap (or Stelvin cap) has been a long and complicated one, and the revolution pretty much began in Australia in the early 1960s, when one of the nation’s oldest wineries – Yalumba (founded in 1849 in the Barossa Valley in South Australia) – saw the future. It was 1964 when Yalumba first began investigating the viability of a screw cap sealing system. It had been used in the past on bottles of spirits, so why not wine? And without a cork, there was no possibility of corking or “cork taint”, when the wine is spoiled most often courtesy of a faulty stopper. Then Yalumba production director Peter Wall approached French manufacturer La Bouchage Mecanique. They had developed and trademarked the first screw cap or Stelcap Vin (wine), thus Stelvin. Then in the early 1970s, Australian winemakers including Yalumba began commercially releasing wine sealed with the Stelvin.

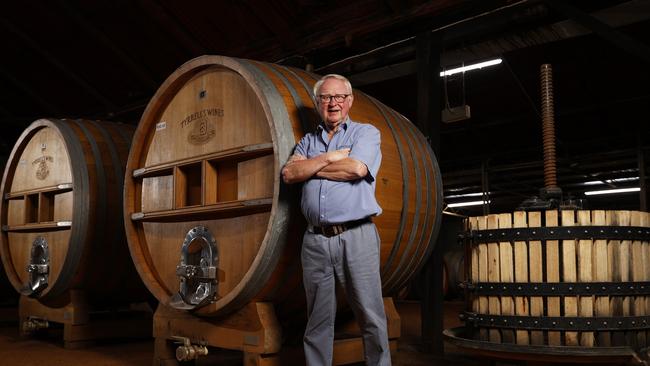

One of those early adopters was Tyrrell’s, another of our grand old winemakers (since 1858) in the Hunter Valley in NSW. Fourth generation managing director Bruce Tyrrell recalls the early frenzied days of the screw cap when Tyrrell’s sold wine to commercial airlines. “The screw cap was probably the best thing to happen to the wine industry in Australia and New Zealand, and around the world,” he said. “We started using them in the mid-1970s doing wine for Qantas economy. And they said, it has to be in screw cap. If you’re down the back of economy and trying to feed a lot of people quickly, you don’t want to be fiddling with a corkscrew. You just want to be able to crack and pour.”

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, too, winemakers were suffering an increase in cork taint. Half their time was spent fretting over the quality of the cork. Bruce never forgot one particular quality control test conducted at Tyrrell’s. They bottled 20 dozen bottles of wine, 10 each under screw cap and cork, and sat them side-by-side in the warehouse for ten years. Identical storage. Same conditions.

“On the tenth anniversary we opened six dozen of each,” he said. “One of the screwcaps rusted out. They were a bit primitive in those days. But everything else was the same. It was perfect. The corks: fifteen of the six dozen bottles were rejected through taint or random oxidation.”

It was time to leave the romance of the cork behind, and it was this early advocacy of Australian winemakers that won the world over to Stelvin.

“We don’t get that nasty bottle of wine that the normal consumer buys in, say, Vancouver, takes it home, serves it at a dinner party, opens it and it smells like a dead rat in the back of the kitchen,” Bruce adds.

“When that happens to consumers, I lose them as a customer. The Stelvin has been one of the great events in our industry. It gave people security.” – Matthew Condon

Avocado on toast PLUS Avocado tissue culture breakthrough

“It was just something I always ate,” says Bill Granger in his 2022 cookbook Australian Food of his famed avocado-on-toast. “It’s true that I put it on toast – but didn’t everyone do that? It was just a quick, healthy breakfast on the run.” Maybe so, but then again maybe not in the way Bill did it when he opened his eponymous cafe bill’s at Darlinghurst in Sydney in 1993. At bill’s cafe, the avocado-on-toast comes sliced, not smashed, but at home at Bill’s table, he prefers it diced into a salsa. Whichever way you spread it, Bill Granger is credited with exporting the Aussie breakfast to the world – first to Japan and then on to his restaurants in London, Korea and Hawaii – and the dish that took hold was avocado on toast.

Speaking of avocados, while Granger was starting a global food phenomenon, a team of Queensland researchers has been working at changing the way we propagate the fruit at the root. In 2021, the University of Queensland’s Professor Neena Mitter developed the “world’s first Hass avocados produced by trees grafted on tissue culture plants”. In Mitter’s trial, tissue culture technology allows for 500 times more avocado plants to be grown from a single 1cm cutting. At the moment her team is generating 25,000 avocado plants in a 10 sqm room. It’s a development that reduces the resources required and time it takes to produce a plant. The breakthrough represents a sustainable technology that reduces the need for water, fertilisers, land and pesticides. Mitter’s breakthrough was highlighted in the keynote speech at the World Avocado Congress in June. What next for her? “What about a seedless avocado?” she posits.

– Jessica Clement

Flat white

The humble flat white is a daily ritual for most Australians, except of course, those who prefer a latte. But did you know flat whites are the second-most ordered drink in coffee houses in the US? (Not that they do it correctly, with their grandé sizing, use of honey instead of sugar and other errors. But we digress). A cherished standard of the Australian cafe scene for decades, the flat white is the love child of the cappuccino, brought to Australia by Italian immigrants in the 1950s. Transported to London in 2011 by Sydney cafe king Bill Granger, the creamy, caffeinated goodness of the flat white took a hold. But its big moment arrived in 2015, when Starbucks put the flat white on its global menu. “What is a flat white?” asked countless news stories at the time. Now everyone in the world knows. Just don’t turn up in Italy and ask your Roman barista for an oat milk flat white. Lactose-free milk is where the Italians draw the line. – Elizabeth Meryment