Vegetarian guru Peter Singer declares reducetarians will help halt climate change

Founding father of the animal rights movement Peter Singer argued the moral case for giving up meat. Now he says anybody willing to cut back could play a role in saving the world.

Behold the vegan Magnum, surely the point at which plant-based eating reaches its zenith. A dairy-free ice cream, pure indulgence, putting paid to the stereotype of hairshirt self-denial linked to the meat-is-murder crowd. The times are all about choice and the meat-averse are spoilt for it. Supermarket shelves groan beneath piles of beefless burger patties and chickenless nuggets and a dizzying array of groceries featuring corny, meat-mocking puns: notdogs, tofurkey, facon, soyrizo.

Plant-based milks such as oat, almond and soy are edging out dairy in cafes across the country. Hungry Jack’s offers a Vegan Whopper and McDonald’s is trialling a McPlant line of burgers and nuggets as fast-food giants scramble for a slice of a global plant-based food market estimated to be worth $162 billion by 2030. Even the tradition-loving RSL got the memo, recently debuting a meat tray that features “butcher-quality cuts” of portobello and cup mushrooms.

Not content with refining the nutritional value and flavour profile of ersatz meat, food scientists are working to simulate the sensory experience of eating it. By genetically modifying an iron-rich molecule called heme, for example, US-based Impossible Foods has replicated the bloodiness of a medium-rare patty in its plant-based Impossible Burger. Or how about a hybrid alpaca-duck burger made from mixing and matching real animal cells in a lab? Singapore already has lab-grown chicken on the menu and the US Food and Drug Administration has cleared the way with a recent ruling that so-called cultivated meat is safe to eat. In February, Sydney-based startup Vow became the first cultivated meat company in Australia to begin the regulatory approval process.

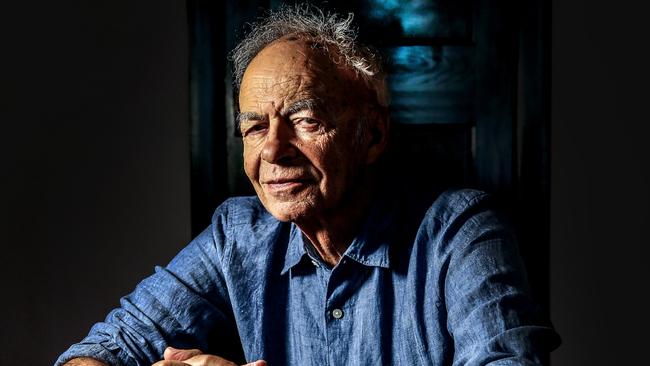

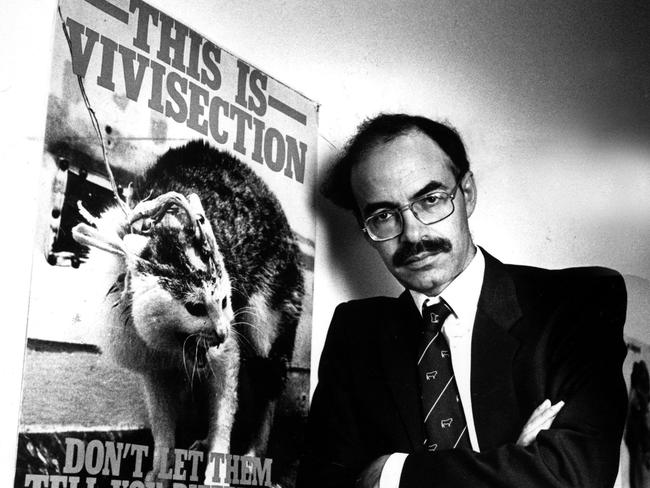

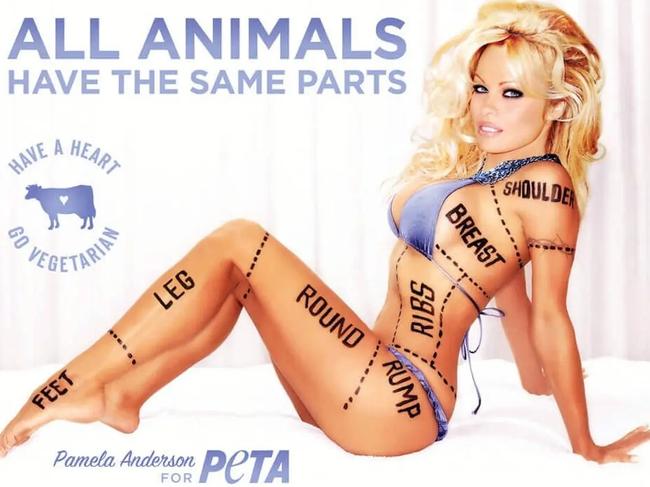

That’s all great, says Peter Singer when I attempt to draw him into an appraisal of this new vegan cornucopia and the futuristic efforts to expand it. Just great. “I’m sure if people like those products and they’re convenient, then I’m very happy for them,” he says. Singer is the Melbourne-born moral philosopher who literally wrote the book on meat-free living with his seminal 1975 text Animal Liberation. Dubbed a “philosophical bombshell” by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) co-founder Ingrid E. Newkirk, the book inspired the worldwide animal rights movement by revealing the extent of animal abuse in factory farms and laboratories. Millions were converted to vegetarianism by Singer’s simple but forceful arguments, and it put considerable pressure on the use of animals in science experiments. Time magazine named it one of the 100 best nonfiction books ever published.

If the founding father of animal rights sounds less than enthusiastic about vegan Magnums (“pretty good”) and Impossible Burgers (“a bit odd”), it’s soon clear why. A public intellectual who has arguably had more influence over how people behave than any philosopher in the world today, Singer’s affect is naturally serious and phlegmatic. He’s an ethicist, not an epicurean. Chiefly, though, he feels it’s all just a little … unnecessary. Singer, 76, stopped eating meat in 1970 to protest the way animals were being treated as mere machines for converting feed into meat, milk and eggs. He points out that he has managed to sustain a meat-free lifestyle for more than 50 years, making “delicious meals just using plants, lentils, beans and tofu”.

He welcomes the flexitarians, the vege-curious and the reducetarians

“I don’t know that I particularly want to eat meat any more – or food that tastes like meat,” he says. “Eating plant-based is actually healthier, and I feel very comfortable and good on that kind of food.”

Singer is prepared to cede some ground, and he does so in Animal Liberation Now, a revised and updated version of his pioneering 1975 text, published this month. In the original, Singer, a professor of bioethics at Princeton University, argued that the way agribusiness corporations treated animals was morally indefensible and that humans were guilty of “speciesism” in giving their own species priority over animals.

Nearly a half century later, science has vindicated the thinker’s stance on the sentience of animals and their capacity to feel pain. The database of evidence about the complex behaviour and nervous systems of a wide variety of species is strong and rapidly growing, with the UK government recently adding ocean-dwellers such as octopuses, lobsters and crabs to a list of “sentient beings”.

Singer still finds factory farming ethically abhorrent and, on its own, a powerful enough reason for not eating meat. But concerns about deforestation and substantial emissions of the potent greenhouse gas methane have made climate change an equally urgent part of the conversation. Urgent enough to make Singer soften a hardline position.

“Climate change is a disaster,” he says, “and simply reducing meat and dairy consumption is a quick and pretty easy way of helping the planet. If you’ve got a large number of people in affluent countries halving their intake, that would actually have a bigger impact on reducing emissions than, say, doubling the small number of existing vegans. I think that’s a reasonable compromise.”

Just two per cent of the Australian population is vegan, but there’s some good news for the world’s chickens, cows and pigs, 83 billion of which are slaughtered globally each year. The number of non-vegetarians looking to swap out some meat in their diet for the good of the planet, the animals or their own health is growing. According to a 2021 Choice survey, 11 per cent of Australians were “considering becoming vegan” in the next five years, and Australia is the world’s third fastest growing market for plant-based foods.

Alongside the vegans and vegetarians, Singer says welcome to the flexitarians (he himself eats oysters and, occasionally, free-range eggs). Welcome the vege-curious and – here’s a new one – the reducetarians. American plant-based advocate Brian Kateman, inspired by Singer’s 2006 book The Ethics of What We Eat, recently coined the word to describe a movement that embraces those who commit to cutting back on animal products to any extent, regardless of their motivation.

Anything that cuts the production of methane by ruminant livestock, estimated to generate 15 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions each year, is considered a bonus. Singer even welcomes the concept of meat grown from cultured animal cells and hopes to see it soon produced cheaply at scale. He points out methane is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide in warming the atmosphere in the first 20 years of its release. “If the next 20 years are crucial, as everybody says, in avoiding completely catastrophic, uncontrollable changes to our climate, then cutting the methane emissions from animals would make a huge difference,” he says. The animal-based food system is also a key driver of deforestation and biodiversity loss: “A lot of the Amazon has already been cleared for beef grazing or else for the production of soy, three quarters of which goes to feed animals.”

The average Australian eats 25 chickens a year, along with a quarter of a cow and just as much pig. They do so, Singer believes, with a kind of wilful ignorance, disconnecting their meal from the macabre reality of its production. “People don’t want to know how those animals lived or died,” he says. “They’ll even say to me, ‘Don’t tell me, you’ll spoil my dinner’.”

Singer’s ethical argument hasn’t changed since 1975. “I think the simplest argument is that if you care about your dog or your cat then there’s no reason why you shouldn’t care about pigs and chickens and cows,” he says. “You would never treat your pet the way those animals are treated in industrialised animal production, so you shouldn’t support it with your dollars when you go to the supermarket.”

When writing the original text, Singer knew he was pushing against deeply ingrained practices and attitudes, as well as a huge agribusiness lobby, but he dared to dream that by now, factory farming would be consigned to history. And yet the majority of animals raised and killed for food are still confined in crowded spaces their entire lives. There have been some improvements in restricting some of the worst forms of confinement. Battery cages for laying hens are now outlawed in the European Union, the UK and some US states, as is the practice of veal calves and breeding sows being kept in individual stalls without room to turn around. “Australia is slowly moving towards these things, but more slowly than the EU,” Singer says.

The pages of Animal Liberation Now bristle with vivid descriptions of the institutional cruelties humans impose on animals: chickens selectively bred to grow so fast their immature leg bones struggle to support their weight; mothers separated from their babies; veal calves deprived of iron to produce white meat.

Despite the explosion of meat alternatives, worldwide meat consumption has more than doubled since 1990, accelerating at an alarming rate as billions around the world escape poverty. In a new introduction, the public intellectual and best-selling author Yuval Noah Harari says that dubbing the treatment of animals in industrial farms “the worst crime in history” would have sounded ludicrous in 1975. “Today, thanks in no small part to the impact of this seminal book, increasing numbers of people accept these ideas as reasonable, or at least debatable,” the Sapiens author writes. Its ideas are, in fact, more relevant than ever, as “we continue to mistreat animals on an incomprehensible scale”. The expansion of China’s animal production, for example, shows no signs of slowing, and many aspects are completely unconstrained by any national animal welfare laws. “As I write this preface, huge skyscraper ‘farms’, 26 storeys high, with 400,000 square metres on each floor, are being built,” Harari writes. “When complete, they will be filled with millions of pigs.”

The Covid-19 crisis did more than hammer home the public health risks of zoonotic diseases, transmitted from animals to humans. It also gave rise to the “nightmarish” scenario Singer uses to open an updated chapter on farming practices. “One of the most sickening things for me was what was euphemistically called the ‘depopulation’ of pigs during Covid,” he says. “When the slaughterhouses were shut down, the pigs [in there] were basically suffocated and heated to death, over a period of about an hour. Probably a million pigs died this awful, slow death.” A much larger number of chickens, turkeys and ducks suffer the same fate periodically due to outbreaks of bird flu, he says.

The suffering of animals still provokes strong emotions for Singer. “I find it sickening but it also makes me angry,” he says evenly over the phone from his home in Melbourne. The professor is recently returned from a contemplative surf, a sport he took up in his fifties. He doesn’t teach the northern spring semester at Princeton, so he’s back in his hometown with his wife of 54 years, Renata, and making frequent trips to Victoria’s Surf Coast. (He does not ponder deep philosophical mysteries while bobbing out the back: “I think things like, ‘There’s a big wave coming through, will I get that one or wait for something smaller?’”) He’ll head back to the US for the fall semester, his last at the Ivy League institution. After 24 years, he says it’s time to retire. “From Princeton anyway, not from work or life,” he adds.

As a utilitarian philosopher, Singer believes the most ethical choice is the one that will produce the greatest good for the greatest number. Over the years he has turned his attention toward ways of minimising misery in the world, chiefly by reducing the avoidable suffering and premature deaths of humans and animals. He’s written dozens of books, and his ideas on eradicating global poverty form the foundation of the “effective altruism” movement.

The plan is to woo people with entirely new meats

His 2009 book The Life You Can Save inspired the formation of a non-profit of the same name to help vet the most effective global charities. Outspoken and political, Singer has often courted controversy. He enraged disability rights activists with his 1979 book Practical Ethics, in which he argued parents should have the right to end the lives of newborns with a severe disability. Singer included conditions such as Down syndrome, spina bifida and haemophilia among disabilities that make “the child’s life prospects significantly less promising than those of a normal child”. The firestorm of rage it provoked reached a crescendo with his 1999 appointment to Princeton. His first day was disrupted by protests as people in wheelchairs blockaded the main university building, with the leader of disability rights group Not Dead Yet famously labelling him “the most dangerous man on Earth”.

More recently, he helped launch the Journal of Controversial Ideas for the discussion of unpopular viewpoints, and has weighed in on robot rights. (No, we’re not close to sentient AI yet. Yes, if and when it does become sentient, it will deserve similar status to humans.)

Behind the whitewashed walls of a hip warehouse conversion in Sydney’s Alexandria, Australia’s first cell-based meat company is gearing up to export “cultured” quail meat to Singapore. Vow is a biotech start-up founded in 2019 by “hardcore carnivores” George Peppou and Tim Noakesmith as a sustainable alternative to the mass slaughter of animals. Vow’s website says the company is “inventing a completely new way to do an entirely new thing”.

Singer’s on board. Next month, in a collaboration between Vow and his The Life You Can Save charity, he’ll join Peppou on stage in Melbourne to talk about “Ethics in the Future of Food”. “I’m not a purist about [cultivated meat],” Singer says. “You definitely start with animal cells, but you don’t have to actually have an organism capable of suffering.”

Cultured meat is meat, but not as we know it. Scientists harvest a small sample of stem, muscle and fat cells from a living animal and grow it in vitro before shaping the flesh into cuts of meat. The major start-ups in the field – Believer Meats, Eat Just and Upside Foods – are US-based, with research facilities and pilot plants producing small amounts of cultured chicken that, they say, is hard to tell from the real thing. Singapore is the only jurisdiction in the world where the sale of cell-cultured meat products has been approved, but the US startups are already partnering with restaurants in anticipation of full regulatory approval.

Vow, meanwhile, has begun the approval process with Food Standards Australia New Zealand. “We’re excited to be bringing our first product, cultured Japanese quail, to Singapore as soon as we are approved for sale,” says Peppou, a former chef with a biochemistry degree. “We expect Australia and the US to follow in 2024.” Vow’s first product is said to have a roasted umami flavour with “aromatic seafood notes”. In answer to an obvious question – won’t people be weirded out by the idea of meat manufactured in a petri dish? – Peppou issues an “important correction”. “We develop our products in a lab, just like all foods from your favourite breakfast cereal to yoghurt [and] we produce cultured meat in a factory,” he says. “From everything we have seen through tastings with consumers and chefs, there is a lot of enthusiasm to trial it.”

Vow’s motto is “Food that is forged, not farmed” and it takes the concept of cultivated meat a step further. Instead of competing with the incumbent meat industry by producing beef, chicken and pork analogues, its food scientists have their eye on more exotic sources of protein and combination flavours such as alpacas, kangaroos and water buffalo. The plan is to woo meat-eaters by inventing entirely new meats that are “tastier, more nutritious, more functional or more exclusive”.

“What we’re talking about here is a behaviour change problem,” Peppou says. “Meat demand is growing faster than we can keep up with and leading to more intensive farming around the world. We need meat eaters like me to choose to add complementary foods into their diets and they’ll only do that when the alternative is far better than what’s already on our plates.” Lions, turtles, zebras and bison: with more than 10,000 species to choose from, there’s no need to be boring, he says.

The Vow folks certainly know their way around an attention-getting stunt. Earlier this year, they made international headlines when they unveiled a giant meatball made from cultivated woolly mammoth flesh at the NEMO Science Museum in the Netherlands. The meatball was created by inserting a mammoth myoglobin gene (responsible for meat’s aroma, colour and taste) into sheep cells, filling any gaps in the thousands-of-years-old mammoth DNA sequence with modern elephant DNA.

“The mammoth meatball started a conversation”

With no way of knowing how a present-day immune system would react to an ancient protein, the meatball was never intended to be eaten. But that wasn’t the point. “We created the mammoth meatball with a very simple mission: to start a conversation about the future of food,” Peppou says. “It really challenges us to think outside the box and imagine a future where meat consumption can be different from what we know today.”

“Talk about improving biodiversity!” says Dr Joanna McMillan of the woolly mammoth meatball stunt. McMillan is one of Australia’s best known nutrition scientists and dietitians and her “nerdy science brain” finds the idea of cultured meat intriguing. She’s wary of a headlong rush to plant-based eating. “What we mustn’t do is focus on sustainability without thinking about nutrition,” she says. “Because I see it all too often being simplified into ‘Just eat more plants and less animal foods’.

“I’m especially concerned about young women buying ultra-processed packaged foods that allow them to easily follow their vegan diet and doing things like switching from dairy to almond milk, which has hardly any nutrition in it at all. Or parents putting their children on 100 per cent plant-based diets without any thought to where they’re going to get their vitamin B12, their calcium, their iron.”

McMillan has done a lot of work in the food sustainability space and finds the search for solutions to be “incredibly complex”. “I think we’ve got to be really careful that we don’t just jump onto this plant-based wagon without thinking about whether it’s really solving our sustainability problems and what the knock-on effects are regarding nutrition,” she says.

Consumers can shrink their environmental footprint in other, potentially more effective ways, she says. “First, stop wasting food – a third of the food produced globally goes to waste,” she says. “And the second thing is about … not eating too much and eating closer to the dietary guidelines. Essentially, that means eating more whole foods and less ultra-processed foods because those things are very energy intensive to create.”

According to Deloitte Access Economics, Australians spent more than $150 million on plant-based meat alternatives in 2019; by 2030, it’s estimated the plant-based food sector will boom to $3 billion. McMillan warns many plant-based “meats” are ultra-processed and very high in salt. “It’s difficult to get right,” she says. “I’m always telling people the best thing you can do is stop eating so much ultra-processed food, yet we’ve got this sort of health halo around these foods. The science is incredible, but it is a little bit frustrating that they’ve just tried to replicate, say, a burger. A burger is not the best example of a healthy meal. I think [plant-based meat] has definitely got a place in future diets, but I’d like to see a shift towards at least trying to make them healthier.

“The reality is, we’re not going to truly know their impact on human health until we’ve all been eating these things for a lot longer.”

Animal Liberation Now (Penguin Random House Australia, $35) is published on June 13