Soldier’s best friend: why the Bushie is a great Australian invention of industry

Since it entered service the Bushmaster has saved hundreds of Diggers from landmines, IEDs and enemy fire – it’s one of our country’s best industrial innovations. | FULL LIST

It’s been called an ugly duckling and even an “armoured Winnebago”, but while the Bushmaster might not win a beauty contest, it ranks as one of the most inspiring lifesaving Australian inventions.

Many people have probably only heard of the Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle in the past year since Australia made a high profile donation of 120 Bushmasters to Ukraine to help repel invading Russian forces. But to Australian Diggers, the Bushie as it is known, has been a soldier’s best friend ever since it entered service in 2005.

And yet, the Bushie itself was almost killed off before it was built, with some in the military believing it could never be made in Australia and that an overseas-built armoured transport vehicle would naturally be better.

The perceived need for an Australian armoured vehicle able to rapidly and safely deploy troops across a large battlefield came from the Hawke government’s 1987 Defence White Paper which imagined that such a capability was needed to defend Northern Australia from small-scale hostile land incursions.

The Australian inventions changing the world

Brain powered: control a computer with your thoughts

It was once the realm of science fiction. Now, a brain-computer interface developed by this Aussie team promises to revolutionise and reshape the way we communicate.

Soldier’s best friend: why ‘Bushie’ is a great Aussie invention

Since it entered service the Bushmaster has saved hundreds of Diggers from landmines, IEDs and enemy fire – it’s one of our country’s best industrial innovations. | FULL LIST

Can these engineers disrupt a billion dollar market?

Their microneedle medical patch designed to monitor the efficacy of administered drugs is among the top Australian medical breakthroughs improving human health. | FULL LIST

Heaven sent: two Aussie punks take over Marc Jacobs’ world

When the fashion supremo needed a breath of fresh air he turned to two Australian creatives - Ava Nirui and Elliot Shields. The pair are now among our leading fashion innovators | FULL LIST

How a Tassie seaweed farm can help save world

Methane-eating seaweed, avocados grown in a lab, and the march of the flat white towards World Domination. In the world of sustainability, food technology and dining, these Aussies are making a global impact. | FULL LIST

Man behind the ‘masterpiece nobody should miss’

He is the pioneer of ‘cine-theatre’ whose latest five-star production is headed to the West End and will feature a Hollywood star. Kip Williams leads our list of cultural innovators | FULL LIST

The Aussie company out to send astronauts to the moon

A plan to send a 25-metre tall rocket into orbit from a North Queensland spaceport is just the beginning for Gilmour Space, who lead our list of Australian tech and gadgetry innovations making an impact in 2023.

In 1996 Lieutenant Colonel Warren Feakes was given the job of working up a concept for the Bushmaster, something which he says he wrote down “on the back of an envelope”.

His team figured the new vehicle had to be able to transport a section of soldiers including food, water and fuel at up to 100km/hr for 1000km without refuelling. And it had to do this while being also able to withstand blasts from very large landmines and improvised bombs.

Feakes then asked a colleague to create a “bomb” by packing a 20-litre drum of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil and then measuring the “net explosive quantity” of the blast. They calculated from this experiment that the vehicle needed to be able to withstand a blast equivalent to 9kg of TNT. They did not design the vehicle to fight – it was not a tank – but it was designed to be a battlefield taxi which could survive a fight and transport soldiers safely. It also had to be comfortable because in the desert temperatures could reach 50 degrees and so it needed to be airconditioned. Bob Roach, a member of the team that welded the steep plates together for the first Bushmaster prototype, also owned a Ford Falcon.

When researching the Bushmaster he measured his car’s seating and steering set up and replicated it so that “When you sit in a Bushmaster it’s as comfortable as sitting in a Falcon.” The key innovation, however, occurred several years later when the designers decided to replace the vehicle’s original flat-bottom with a V shape to help deflect any blast outwards – something which Australian military engineers had observed in army vehicles in South Africa.

During the trials Roach would drive the prototype around the streets of Bendigo in Victoria, where they were to be built. He even sometimes drove a Bushmaster to Adelaide to visit his wife, passing startled drivers on the freeway. After 12 months of trials, the Bushmaster won a three-way tender and defence initially contracted the then government-owned ADI to build 370 of them.

But it was not an easy birth. Defence came up with 23 major changes to the vehicle, which required a significant redesign, making the early Bushmasters unreliable. Costs soared, schedules slipped and Defence in 2001 wrote to the Defence minister Robert Hill to recommend the project be cancelled. But fortune intervened when Hill asked Major General Peter Cosgrove, who had commanded the international task force in East Timor, what he thought of the Bushmaster. Cosgrove said he was a strong supporter of the Bushie and he urged Hill to continue with the project. Luck would have it that when the first Bushmaster entered service in 2005 it was immediately in demand because of Australia’s military mission in Iraq and then later in Afghanistan where IEDs were a deadly threat.

“The Bushmaster’s capability wasn’t fully appreciated until it was in action,” says Brendan Nicholson, of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute who has written a short history of the Bushmaster project.

In both Iraq and then Afghanistan, the Bushmasters did their job superbly, withstanding multiple blasts from IEDs. Although 41 Australians were killed in Afghanistan, no Australian soldier has ever died in a Bushmaster.

It now forms part of the armed forces of eight other countries around the world. – Cameron Stewart

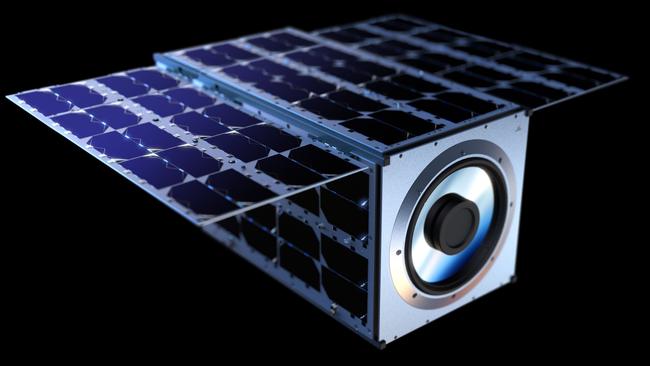

TOLIMAN Project

At the very forefront of the search for life beyond our solar system is NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a Russian-born Israeli billionaire and a crack team of scientists at the University of Sydney led by Professor Peter Tuthill. All three form part of the TOLIMAN project, which is developing the TOLIMAN space telescope aimed at detecting exoplanets, specifically in the Alpha Centauri system, where scientists believe we may find the “Goldilocks” planet with conditions most similar to our own. Work on the project began in April 2021 and the telescope, a new design that uses a diffractive pupil lens to make it easier to detect perturbations of star movements (the telltale signs of orbiting planets), is expected to be launched into orbit next year. “Getting to know our planetary neighbours is hugely important,” Professor Tuthill says. “These next-door planets are the ones where we have the best prospects for finding and analysing atmospheres, surface chemistry and possibly even the fingerprints of a biosphere – the tentative signals of life.” The project has the support of the Breakthrough Initiatives, founded by the billionaire investor Yuri Milner, to bolster the search for extraterrestrial life. – Jessica Clement

Business class

Any truly great innovation will attract a queue of geniuses claiming the idea. Business Class air travel is no different. During the 1970s several international airlines wrestled with a different model to the prevailing First Class and then economy or “cattle class”. Was there a financially lucrative zone in between the two? A special section dedicated to the wants and needs of business people who might have some work to do on a long flight? KLM and Japan Airlines introduced some notional goodies – priority check-in and baggage handling – for their highest-paying economy passengers. Then Thai Airways took the idea a step further, putting full fare economy passengers in their own section between first class and cattle, replete with the latest magazine and a bar. But it was Qantas in 1979 that refined the idea of Business Class and shared it with the world. Comfortable, lounge-style seats. Better quality food and fine wines. Separate check-in. A new flying class was born and – excuse the pun – it took off. – Matthew Condon

Aircraft slide-raft

n 1965, Jack Grant, an unassuming Qantas operations safety superintendent in Sydney came up with an idea that, for decades, was and remains an innovation that any aircraft passenger hopes they never have to think about, let alone use. Grant was the mastermind behind the escape slide-raft – an inflatable slide that helped you quickly exit an aircraft that had crashed at sea which, when unhooked from the stricken plane, instantly became a life raft. For years jet aircraft had life rafts stored overhead throughout the cabin but Grant’s idea was simple and fast, and after rigorous testing and sea trials, it was ultimately accepted by aviation authorities around the world and has remained a critical, and mandatory, safety staple of passenger aircraft ever since. – Matthew Condon

Derlot

he odds are quite high that at some point you’ve actually sat on a Derlot, somewhere in the world, without realising. That is a piece of furniture created by Brisbane-based designed Alexander Lotersztain and produced by his company, Derlot. Born in Buenos Aires, he drifted to Queensland as an enthusiastic young surfer, then worked in Japan, Italy and Spain before setting up shop back in Brisbane. He started off with chairs, then rolled out his “twig” seating systems – indoor/outdoor twig-shaped benches that can be moved around and reconfigured, depending on the user’s desire for privacy or sociability. They can be spotted in airports across the planet. (They even come with an anti-graffiti sealant).

Then came sectional sofas. Most recently, he has produced seating systems for American Airlines that will feature in the new terminal at the Dallas Fort Worth International Airport. The success of Derlot, which has offices in Brisbane and Los Angeles, and manufactures primarily out of Melbourne, is a combination of contemporary visual appeal and functionality. Its ethos? Meaningful and human-centred design. With the occasional fun twist. Derlot’s influence is all over a rapidly evolving Brisbane CBD (in time for the 2032 Olympic Games), from universities to restaurants to surf clubs. And, slowly but surely, to the wider world. – Matthew Condon

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout