In Gareth Evans’s compelling new political memoir, destined to become a standout in the burgeoning genre, he writes about “HPtFtU”: the Human Propensity to F..k things Up. It is an affliction, whether in our genes or mental wiring, that he says we all suffer from.

Evans, during his stint as a minister in the Hawke and Keating governments, including as foreign minister (1988-96), was no exception to this rule. He was always driven and ambitious, his ego rarely masked, and he was prone to volcanic eruptions or putting his foot in his mouth.

In 1983, as attorney-general, Evans organised for RAAF jets to photograph the Franklin Dam, which the Hawke government pledged to stop. “Don’t call me Biggles,” he joked to journalists, who used this moniker for the rest of his career. He then relied on the “streaker’s defence” to explain his actions. “It seemed, your worship, like a good idea at the time.”

Bob Hawke stripped Evans of the portfolio — his dream job — the following year and he went on to serve as minister for resources and energy (1984-87) and later in transport and communications (1987-88) before becoming foreign minister. Evans, having rebuilt his political stocks, became a successful minister but never lost his exuberance.

He was the first politician to get the F-word entered into the Hansard of an English-speaking parliament in two centuries. He once threatened to “garrotte” Bronwyn Bishop on the floor of the Senate. And during his unhappy time as deputy Labor leader (1996-98) he admitted to suffering from “relevance deprivation syndrome” — a term that is now part of the political lexicon.

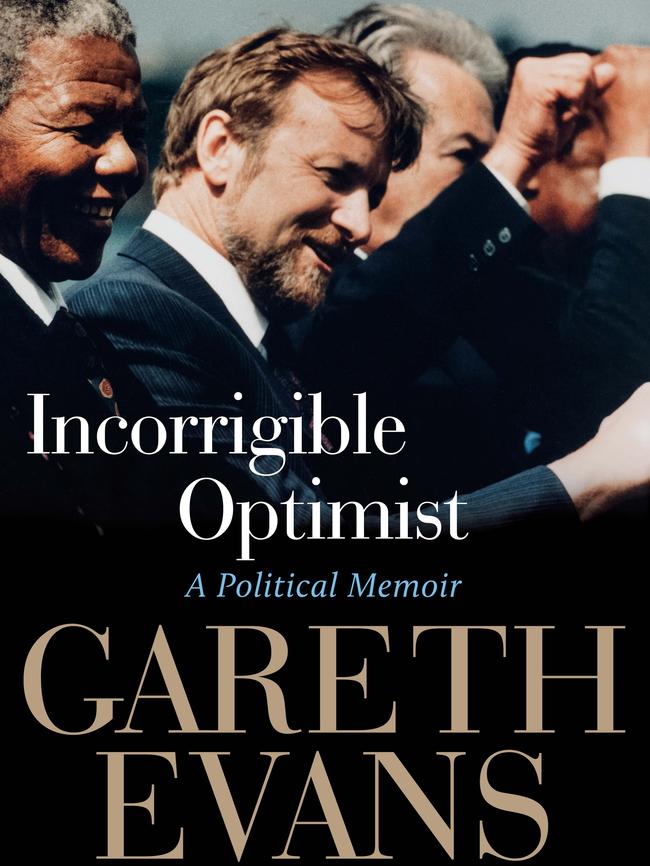

In Incorrigible Optimist: A Political Memoir (MUP), Evans writes thematically on issues that reflect different phases of his public life as an opposition senator (1978-83), minister (1983-96), head of the International Crisis Group (2000-09) and chancellor of the Australian National University since 2010.

It is focused on policy and politics with insights into his early life as a student and backpacking around the world. It is engaging and insightful and, uncharacteristically, self-critical and deprecatory. There is, however, no mention of his affair with then Australian Democrats leader Cheryl Kernot. Instead, it mixes highbrow policy with anecdotes that serve as a practical guide to policymaking and a serious contribution to history.

Evans’s analysis of foreign policy, including his case for “middle power diplomacy” and a less compliant attitude towards the US, is leavened by a perceptive analysis of contemporary global politics. Chapters on the “responsibility to protect” the framework for humanitarian intervention and the challenges of nuclear disarmament are absorbing.

While Evans made his mark as foreign minister, the finest moment of his public career was as leader of the government in the Senate (1993-96) when he shepherded the Native Title Act 1993 through the upper house against almost impossible odds.

Evans’s reflections on how to succeed as a minister, prime minister and government are timely given the state of modern politics. He argues there are two basic motivations of politicians: idealism and megalomania. Too many are there for “the joy of playing the game” rather than “getting good things done”.

His tips for being an effective minister are: having intellectual ability, good judgment, communication skills, organisation and management ability, empathy and a sense of humour. To this he adds resilience and a fair dose of good luck.

To be a successful prime minister requires serious intellectual capacity, higher-order judgment and first-class temperament. He also suggests a strong work ethic, unimpeachable personal integrity and a clear vision. And there is one more characteristic required: “a degree of self-belief that defies normal human inhibition”.

According to Evans, Hawke’s strengths were his ability to craft a grand narrative, his connection with voters, his collegiate approach to cabinet and his personal and institutional discipline. Paul Keating’s strengths, in addition to being a policy innovator and driver, were his strategic direction and capacity to communicate.

Looking back on what made the Hawke and Keating governments successful, Evans draws several lessons. He pinpoints their vision and direction, governing processes, the contestability of policy with ministers given free rein and cabinet being a clearing house, consultation with voters and stakeholders, and the ability to communicate policies.

Evans makes the entirely valid point that there was no absence of egos or ambitions or colliding personalities that make the Rudd-Gillard or Abbott-Turnbull governments unique. The Howard government also had plenty of those. The point is they could bottle these strains because they were effectively managed, there was respect between ministers and they were driven by policy goals.

While few would disagree that the quality of politicians has degraded, Western liberal democracies around the world are facing many of the same challenges: economic change, cultural anxiety and security concerns. As a result, Evans argues, new approaches to politics and policy are evidently needed. He remains an incorrigible optimist.

In recent years there has been an explosion of books by politicians eager to burnish their reputation as writers. Some have been very good. But too many politicians are writing memoirs before they have really achieved anything. Evans is in a different league. His memoir brims with intellectual clarity and substance infused with national and international experience in policymaking. Politicians should read this book. It offers a window into a time when politics was not so dysfunctional and policy was invested with rigour and purpose.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout