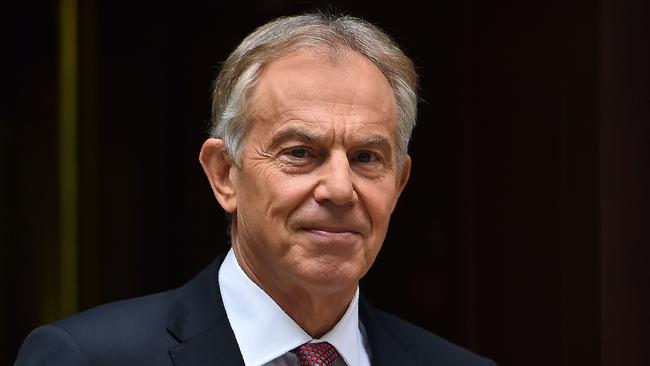

Tony Blair worries about the future of centre-left political parties around the world, including the British Labour Party and the Australian Labor Party, and fears his centrist approach to governing may no longer be a viable political project.

The party that Blair returned to power in 1997, which dominated British politics for a decade, rewriting the political rule book and leaving a substantial legacy, last month re-endorsed the ultra-left Jeremy Corbyn as its leader — a man who Blair believes has probably relegated Labour to the political wilderness.

“The politics of protest is unlikely to see you elected to government, not because it’s too principled or too Left but because it’s too wrong,” Blair tells Inquirer. “You have to demonstrate leadership, set out a vision for the future and convince people of all political persuasions and none that you have the right answers to the questions facing the country. If that compelling case is not made, then the party will not only fail to live up to its founding principles but will also fail to represent the interests of those people who need a Labour government.”

In a wide-ranging interview, Blair speaks about his centrist political creed, identifies the pathway back to power for British Labour and Australian Labor, speaks about Brexit and Donald Trump, religious extremism and globalisation, and reflects on his legacy and interests since leaving Downing Street in 2007.

Blair was elected Labour leader in 1994. The party had been out of office since 1979 and had to be remade. Blair worked with other reformers such as Gordon Brown, Peter Mandelson and Alastair Campbell to create New Labour. Modernisation was their mantra. They looked to Bill Clinton’s New Democrats and the Labor Party led by Bob Hawke and Paul Keating as role models.

The key lesson learnt? That Labour succeeds when it occupies the political centre and wins over mainstream voters. Blair says this is vitally important to understand for British Labour and Australian Labor.

Both lost the past two elections and their support has tumbled to near-record lows.

“The lessons are very clear but there is a reluctance to learn them,” Blair says. “If you are a progressive political party you’ve got to have enough centre ground support to form a majority; otherwise you can’t win. Second, you’ve got to own the future. You can’t just be trying to recapture the past. Third, you’ve got to have solutions that are radical but seem practical to people. And finally you’ve got to be a party of government and not a party of protest.”

This logic is compelling but, as Blair says, it is often forgotten. Parties can become comfortable and complacent in opposition. But they are lessons that Bill Shorten must also learn if he is to lead the Labor Party back to power.

“The Australian Labor Party is frankly in significantly better shape than the British Labour Party,” Blair says. “I think that Bill Shorten did his very best at the last election. I think it was always a tough election to win. But I think the lessons from our respective times in government are clear. Plus you’ve got to have a leadership which appeals to the country. The leader has got to be able to carry the country.”

Blair places a premium on leadership that is able to persuade. Yet Shorten has never been popular. The last Newspoll saw his approval rating at just 36 per cent and his disapproval rating at 51 per cent. He lags Malcolm Turnbull, who is also unpopular, as preferred prime minister by 33-44 per cent.

It is unimaginable to think Corbyn could ever win over British voters. His policy prescriptions are redolent of the failed policies of the Labour Left in the early 1980s — only far worse. Yet he is popular with party members. He recently defeated the more moderate leadership challenger, Owen Smith, by 61.8 per cent to 38.2 per cent.

Former leader Neil Kinnock (1983-92) recently said the party will not return to power in his lifetime. But Labour is unlikely to split, as it did in 1981 when the breakaway Social Democratic Party was formed. The party was then led by left-wing intellectual Michael Foot (1980-83) but was under siege by more radical types such as Tony Benn. However, Blair says the party is in worse shape today than it was then.

“In the 1980s the ultra-left tried, but failed, to take over the Labour Party,” Blair explains. “When I first met Michael Foot, I was the lawyer for the Labour Party trying to expel the Militant Tendency from the party because of the damage they were doing. We had a leadership that was OK — I don’t think ever capable of winning an election — but it was basically from the traditional Labour Party. The difference today is that the Labour Party has a leadership that is ultra-left, and the Labour Party never, in its 100 years of history, has had that.”

In recent decades, globalisation and deindustrialisation have weakened the traditional blue-collar constituencies of the two fraternal parties while progressive, post-materialist, voters are shifting their allegiances elsewhere. Australian Labor’s vote at the last election was just 34.7 per cent. In the 2015 British election, Labour’s vote was a pitiful 30.4 per cent.

The task ahead, Blair argues, is not simply to balance aspiration with compassion and economic enterprise with social justice. The key is to unify around values that speak to a broad constituency but one anchored in the centre. It is a mistake to only speak to a core constituency.

“There is nothing wrong with being ambitious and aspiring to do better. Indeed, that’s what progressive parties were called into politics to do,” Blair says.

“If you don’t create the wealth you’re not strong enough as a country to help those who are most vulnerable. And if you are not reforming in a world of change — if you are not change makers — then you just become small-c conservative.”

A political party must be able to define its traditional values within a contemporary policy framework. “The risk always for a progressive party is they confuse ends and means,” Blair says. “They become locked in a certain policy view that is for one time but not for all time. The result of that is that you go backwards and not forwards. And if the country feels that about you, then they won’t elect you.”

But is a union and mass membership party structure a help or a hindrance in a world buffeted by digital disruption, vast changes to work and family life, and a society that views organisations governed by rigid procedures as archaic? Today both parties are less representative of the community than they once were.

“I’m not sure that a traditional political party operating in the traditional structures really works,” Blair suggests. “Because people are connected online, they operate quite differently. However technology changes the way we do it, any political party that wants to be elected has got to be sufficiently in touch with the people who they are seeking to represent. Otherwise, what happens? They lose.”

In Britain and in Australia, unions have become dominant in policy formulation, candidate selection and deciding who the leader is. But in workplaces, unions continue to decline. Blair says unions need to modernise.

“There is enormous insecurity in the workplace today and people need unions,” Blair says. “But if they believe that unions are quasi-political or a somewhat old-fashioned collective that don’t really speak to the new world of work, then the risk is the unions will end up becoming a bastion of the public sector where change happens more slowly and jobs are more fixed.”

Blair identifies a creeping trend: unions are no longer at the vanguard of change. “If they lose touch with the private sector that can be very dangerous because unions themselves can become a small-c conservative force. If the unions can forge a new way of representing people at the workplace they will once again become a strong force within politics, and once again their link to the Labour Party will be useful.”

The former British prime minister is clear-eyed about the challenges facing centre-left political parties around the world. And his analysis of geopolitics is as insightful as any on offer. Yet Blair’s legacy remains a matter of fierce debate in Britain.

He led Labour to three election victories and his approval rating edged up over 90 per cent in his early years. He represented a new generation leader who seemed to have the magic formula for politics. But he became synonymous with political spin, had a troubled relationship with Brown and was discredited by the Iraq war.

Blair is proud of his achievements, especially the minimum wage, introducing civil partnerships and the peace process in Northern Ireland. The Bank of England was given independence. There were reforms to health, education and child services. Crime fell. Power was devolved to Scotland and Wales, the House of Lords was reformed and Londoners were able to elect their mayor. The Human Rights Act and the Disability Discrimination Act were introduced. And London won the 2012 Olympics. Blair says his government was about turning Britain into “a modern society” and changing how “Britain sees itself in the modern world”. Yet Britain is a radically different place today, and has now voted to exit Europe.

A recent YouGov poll found most Britons regard themselves as occupying the centre of the political spectrum. The leader they placed closest to the centre was not Theresa May or David Cameron, or Corbyn or Ed Miliband, but Blair. Yet Blair recognises centrism is in retreat.

“There is a huge polarisation between left and right,” he says. “You can see this in the US with Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. When I was prime minister, we were the strong players in Europe and we were the strongest ally of the United States. Today we are on our way out of Europe and we are no longer the strongest ally of the United States — or certainly there is a question mark as to whether we are.

“The Labour Party has obviously gone ultra-left and we’ve got a Conservative prime minister leading us to Brexit. The centre ground, which had been hotly contested, has now been largely abandoned. There is a risk that you end up with a country divided by two quite separate political conversations: a very right wing conversation and a very left wing conversation. And these two groups of people don’t really speak to each other very much and get constantly angry about the state of the world. Therefore, solution-driven, pragmatic, centrist politics is on the defensive.”

Slower economic growth and falling, or stagnant, living standards are fuelling a populist backlash against immigration, trade and investment in Europe, the US and Australia. But Blair says globalisation must be defended and entrenched because it, more than anything else, provides economic opportunities and brings the world closer together. This is a focus of his Faith Foundation and Africa Governance Initiative.

“What holds back globalisation?” he asks. “No 1, it is a close-minded attitude, not an open-minded attitude to the world. That is why religious extremism is such a big challenge. Much of this is based on a perversion of Islam which comes out of the Middle East, and that is why it is a major focus of my time. Secondly, the biggest inhibitor to development, and the therefore biggest inhibitor to countries taking advantage of globalisation, is poor governance. So that is why I work on the governance side in Africa and elsewhere.”

The conversation steers itself back to Blair’s faith in centrist politics. It is, he suggests, the solution to political polarisation, economic insecurity and social harmony. “I spend a lot of my time thinking about how centrist politics makes a comeback because it is only from the centre ground that you will get answers, rather than anger, about globalisation.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout