Billy McMahon has long been regarded as a pathetic politician, endlessly scheming and riven with paranoia, and an incompetent prime minister who was out of his depth and became a figure of ridicule as he led the long Coalition government at its fag end and to defeat in December 1972.

To be compared to McMahon is the ultimate political insult. He is probably Australia’s worst prime minister, an embarrassment to the Liberal Party with few redeeming qualities and with a negligible legacy after a miserable 21 months in the top job.

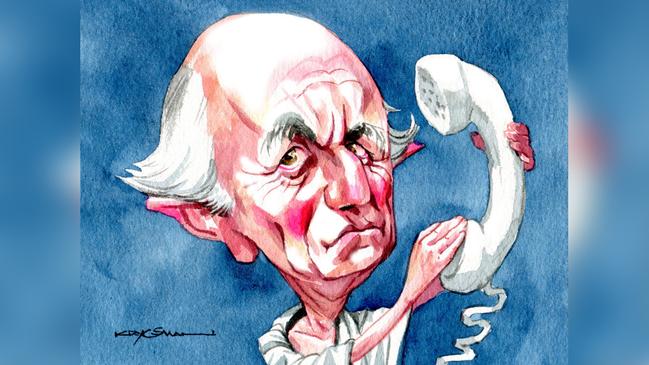

It is not surprising that biographers have overlooked McMahon. Who would want to invest so much time writing about the butt of so many jokes? But Patrick Mullins’s Tiberius With a Telephone: The Life and Stories of William McMahon (Scribe), published this week, is a welcome addition to prime ministerial biography.

It offers the only full account of McMahon’s life, making use of new interviews and diligent archival research, and although it is too long for such an insignificant prime minister — weighing in at a doorstopping 776 pages — it is an engaging and informative read. (The title is inspired by one of Gough Whitlam’s best lines.)

McMahon promised to write the story of his life. He toiled for years and, until his death in 1988, periodically spoke of it going well. He said it would make for compelling history.

Former staff, academics and journalists tried to help but were fired or gave up in exasperation. Here, Mullins intersperses the biography with the tortured history of the never-published book, drawing heavily on former journalist David Bowman’s diaries and documents.

Having read draft chapters of McMahon’s long-lost autobiography, it remains a mystery to me as to what the budding memoirist was doing for the last decade and a half of his life. His reputation surely would have fallen further if the book were finished and published (a lesson Kevin Rudd did not heed).

“For a man so fixed in his views, seemingly so out of time, apprehending that change and wrestling it into a convincing book would have been a mighty, mighty task,” Mullins writes.

“McMahon could not admit fault. Would not admit fault. Rarely even saw fault. And that would be crippling.”

It is a pity that Mullins did not secure access to McMahon’s vast papers at the National Library of Australia. Having waded through them for a previous and forthcoming book, they reveal McMahon to be even worse than we thought.

He documented hundreds of phone calls, meetings, and cabinet and party deliberations in what he called “aide-memoires”. While sorting fact from fiction is a challenge, a fuller use of these would have added immeasurably to the book.

While McMahon was regarded as a joke prime minister, he served as a member of parliament for 32 years and was a minister in the Menzies, Holt, McEwen and Gorton governments. He had stints as treasurer (1966-69) and minister for foreign affairs (1969-71) and deputy Liberal leader (1966-71). It still astonishes that he had partyroom support and the backing of the powerful Packer media family.

In the 1950s, McMahon was seen as an up-and-coming politician. He was regarded as intelligent, capable and even stylish with a playboy reputation. (Mullins confirms that he was not, despite the rumours, homosexual.) He also was an early proponent of rational free-market thinking, especially on trade protection and deficit reduction — an important insight into McMahon.

By the time McMahon had wheedled his way into the prime ministership, having consistently undermined Harold Holt and John Gorton, he was long beyond his prime and too old, at age 63. Few in his cabinet trusted him, journalists scorned him and voters mocked him. He did not have authority, credibility or respect.

He often exaggerated, misled or lied to colleagues and journalists. He leaked repeatedly from cabinet. He had a squeaky voice, and did not look confident in parliament or commanding on television. He was mercilessly parodied by cartoonists and comedians. He was said to look like a Volkswagen Beetle with both front doors open.

Mullins argues that McMahon has become “a by-word for failure, silliness and ridicule” but shows how he was, in truth, “a mass of contradictions and change”. He was charming, but ruthlessly ambitious. He was principled, but often politically expedient. He was determined, but lacked self-awareness and empathy.

When McMahon’s cabinet papers were opened more than a decade ago, they revealed a prime minister who was indecisive or vigorously active in trying to grapple with old and new issues. He seemed to be caught between the old Menzies era and the emerging Whitlam years. Mullins makes good use of archival records to tell this story.

The biography tries to boost McMahon’s reputation as a reformer who governed during a period of “critical change”.

Mullins highlights, among other things, establishing commonwealth involvement in childcare; setting up an urban and regional development authority; new trade practices legislation; expanding funds for schools, colleges and universities; and withdrawing combat troops from Vietnam.

Yet these policies followed those of earlier governments or were overshadowed by larger, and more lasting, initiatives of subsequent governments.

This overdue biography illuminates the politics, policies and personalities of a fading era. It will do little to elevate the standing of McMahon within the Liberal Party, among historians or in popular memory.

But at least now there are two or three other short-serving Liberal prime ministers who also left office rejected, bitter and with few lasting achievements. That, at least, would make old Billy happy.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout