RBA interest-rate hikes push family inflation into double digits

The sharpest rise in worker living costs this century has Australians under the pump and the Albanese government under pressure to provide relief in Tuesday’s budget

Working families are being squeezed by a near double-digit jump in living costs, well above official inflation, with a spike in mortgage charges, insurance premiums and food prices leading to the biggest plunge in household purchasing power this century.

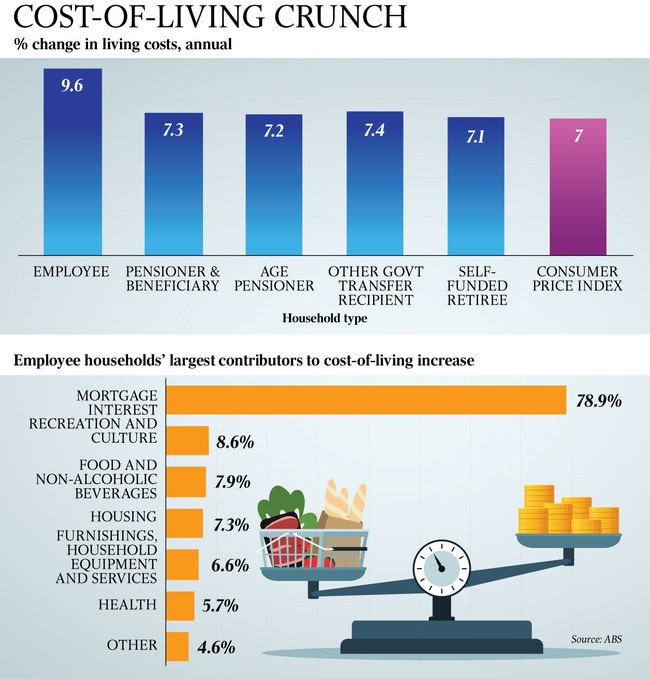

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, all household types – pensioners, welfare recipients, employees and self-funded retirees – have seen living costs rise faster in the year to March than the current headline inflation rate of 7 per cent.

The RBA’s aggressive monetary tightening to suppress inflation over the past 12 months is driving the blowout in workers’ living costs, with mortgage interest charges rising by an annual 78.9 per cent in March, up from 61.3 per cent in the year to December.

On Wednesday, Jim Chalmers said the federal government “understands that people are under the pump right now” but played down the prospect of a broad and hefty relief package in Tuesday’s budget given the nation’s inflation crisis.

“One of the difficult judgments that we have to make, as we put the finishing touches on this budget, is how to provide that cost-of-living relief that people need,” the Treasurer said.

“How do we target it at the most vulnerable Australians, at the same time as we show restraint elsewhere in the budget.”

A day after the central bank warned of persistent high inflation and stunned borrowers by raising its cash rate target to 3.85 per cent, its 11th increase in this tightening cycle, a senior RBA official said Australia’s surprise population surge could turn out to have “unanticipated or more pervasive” effects on inflation and the labour market.

ABS head of prices statistics Michelle Marquardt said the annual rise in the five living cost indexes ranged from 7.1 per cent for self-funded retirees to 9.6 per cent for employed people.

“The magnitude of price changes varies between household types due to their different spending patterns,” Ms Marquardt said.

She said the living cost indexes included the impact of mortgage interest charges, but the consumer price index did not, as it included the cost of building a new dwelling instead.

“Employee households were particularly impacted by increases in mortgage interest charges, which are a larger proportion of their spending than for the other household types,” she said.

The ABS said the rise in employee living costs was the largest increase since this series started in 1999.

The last time the CPI recorded an annual increase of 9.6 per cent was in 1986.

All household types, except self-funded retirees, experienced a quarterly increase in living costs higher than the 1.4 per cent CPI rise, with age pensioners’ costs rising the most at 2.2 per cent, although their payments are adjusted twice a year by the higher of two inflation measures, CPI or the pensioner and beneficiary living cost index.

Higher prices for health, housing, food, insurance and interest charges contributed to increased living costs for all household types.

The ABS said self-funded retirees have a larger proportion of their spending on international holiday travel and accommodation than the other households. “As international holiday travel and accommodation prices fell in many destinations due to the start of the off-peak season, this had a bigger impact on self-funded retirees,” Ms Marquardt said.

Other ABS figures showed retail spending rose by 0.4 per cent in March, with economists estimating a fall in volume over the first three months of the year, after inflation, following a real decrease in the December quarter.

Commonwealth Bank senior economist Belinda Allen said she expected “consumer spending to slow from here as the impact of higher interest rates intensifies”.

“The fixed-rate home loans roll-off is just gaining pace and variable-rate mortgage holders will face another lift after the latest interest rate hike by the RBA at May’s board meeting,” Ms Allen said.

On Wednesday, RBA head of economic analysis Marion Kohler said the central bank was expecting a further decline in consumer price inflation over 2023, as energy prices eased and the end of the global supply crunch led to falls in goods prices. “Two competing forces are driving the inflation outlook,” Dr Kohler said in a speech to CEDA in Perth.

“The ongoing tightness in the labour market and high level of demand for services lead us to expect domestic inflationary pressures to continue.

“But the faster recovery in the population could turn out to have unanticipated or more pervasive effects.

“We will also be carefully monitoring how the competing forces affecting both consumer spending and the labour market are playing out, and how the easing in cost pressures coming from global supply chains translates into domestic prices.”

RBA governor Philip Lowe told a business gathering in Perth on Tuesday evening the board was “deadly serious” about returning inflation to its target range of 2 to 3 per cent by the middle of 2025; otherwise the nation would be in a “world of pain”.

“We will do what’s necessary to bring it down,” Dr Lowe said.

“If you believe that, then I hope in your business decisions you don’t put your prices up as much and I hope it reflects the outcomes in the labour market as well.”

In the question and answer session, Dr Lowe repeated his call for Australia to embrace reforms to lift its productivity growth, which would help the RBA in its quest to bring down inflation.

“As a nation, as business people, as community leaders, as government people, we need to put our shoulder to the wheel here and do what we can to lift productivity growth because that’s the only way we can have faster growth in real wages,” he said.

“It’s the only way to support the Budget, where there are increased needs and it’s the way to improve our living standards.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout