Australia will experience biggest two-year population surge in its history, with an extra 650,000 migrants this financial year and next

Australia will experience the biggest two-year population surge in its history, with an extra 650,000 migrants this financial year and next.

Australia will experience the biggest two-year population surge in its history, with an extra 650,000 migrants across this financial year and next driving a 900,000 jump in the number of residents.

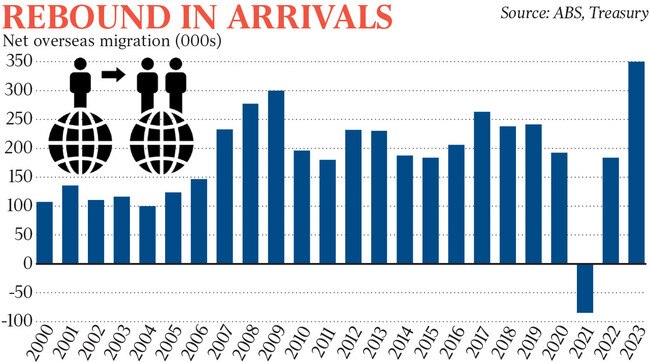

As the nation emerges from Covid-19 lockdowns and skills shortages persist in the services sector, the return of international students and working holiday-makers has produced a sharper rise in migrants than the “Big Australia” era of 2008-09.

With the Albanese government’s second budget six weeks away, Treasury officials are adjusting the fiscal statement’s economic forecasts to reflect the surprise population boom.

The influx of tourists, foreign workers and students is boosting spending, the tax take and demand for services, particularly housing, where the government’s concerns are greatest given extremely tight rental markets.

In the first three months of this financial year, there was a net inflow of 106,000 migrants, which Treasury’s Centre for Population said was the largest quarterly addition in the history of the data series compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics since 1979.

In the year to September, the ABS said net overseas migration was 304,000, the highest annual rise since March 2009, with NSW and Victoria accounting for two-thirds of the increase. With migration responsible for more than 80 per cent of elevated population growth in the September quarter, economists expect continued strong inflow to prop up consumer spending and to ease chronic labour shortages in a full-employment economy.

Jim Chalmers has revealed net overseas migration this financial year is likely to be 350,000, perhaps more, a 50 per cent rise on what was expected in the October budget and January’s annual population statement. The Treasurer said the migration surge was a key underlying factor in the May 9 fiscal package, which would focus on cost-of-living relief, productive investment, and funding the care economy, defence and essential services.

Prior to the pandemic, net overseas migration was expected to add 1.2 million people to our population in the five years to June 2024. Now, according to Dr Chalmers, the revised figure is likely to be 950,000 or about 250,000 less than was expected by Treasury in its mid-year economic and fiscal outlook in late 2019. With a net contribution from migration over the past three years of just under 300,000, that implies net overseas migration of 650,000 over this year and next.

The previous two-year high was 577,000 in the 2008 and 2009 financial years, when then prime minister Kevin Rudd urged the nation to embrace rapid population growth. “I actually believe in a big Australia, I make no apology for that,” Mr Rudd said in October 2009, after projections showed the nation was on track to reach 35 million people by 2050.

“I actually think it’s good news that our population is growing.”

The annual natural increase in population – that is, births minus deaths – is currently 123,000. On these trends, Australia’s population will be almost 27 million by June next year.

The latest Treasury projections show our population at just under 30 million in mid-2033.

“Bigger is not better, it’s just bigger,” independent economist Chris Richardson said of the reverse in the pandemic’s population shock.

“It’s good for the construction industry. We haven’t been building enough homes.

“Covid pushed us into smaller households but we definitely need more supply.”

In the first year of the pandemic there was a net outflow of 85,000 migrants, as students and workers on temporary visas returned to their home countries, and near zero growth in the population. According to the Department of Home Affairs, there were 110,000 more student visa holders in Australia in the 12 months to the end of February, bringing the total here to 583,000.

Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil said the return of students was “a promising increase” but still below 2019 levels. “This data is a welcome indicator of the ongoing recovery from the pandemic and a reminder of the critical role migration plays in our economy, but also shows that we still have a long way to go to fill the gap in our workforce left by the pandemic,” Ms O’Neil said.

“There are obvious changes that we have made to the migration system to undo some of the damage done by the years of neglect under the previous government, and the department has already reduced the massive visa backlog by 40 per cent, but we want to go further.”

In September, Ms O’Neil announced a wide-ranging review of Australia’s migration system

An interim report from its three reviewers was due at the end of last month and is expected to contain key priority recommendations for the 2023-24 budget.

Ms O’Neil said the review would provide “comprehensive analysis of what we can do to ensure that we are getting the people we need, providing opportunities and ending the churn and exploitation which … has become a feature of our migration system”.

In response to calls from employers to ramp up the migration program, the Albanese government increased the cap on permanent migration from 160,000 to 195,000 for this financial year, with 70 per cent of places allocated for the skilled stream.

The five-yearly review of productivity by the Productivity Commission, released this month, said skilled migration needed to be improved to produce a greater economic dividend. The report also noted high levels of migration could lead to road congestion and pressure on services, as well as reduced wages for some workers.

After 10 straight rises in official interest rates, National Australia Bank economists said a key support in the housing market was the rapid recovery in population growth. “This has contributed to a sharp tightening in the rental market where vacancy rates have fallen to around or below 1 per cent in most cities,” NAB said.

Growth in rents is now tracking at about an annual 11 per cent in aggregate across the capitals.

“The strong rental market, strong population growth and a healthy labour market are all likely offsetting some of the pressure from reduced borrowing capacity,” NAB said.

A senior government source said the population rebound was driven by one-off factors after the border reopening, rather than a marked shift in policy.

Annual net migration inflows would return to the pre-pandemic 10-year average of around 230,000.

Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy told a Senate hearing last month temporary migration had recovered faster than expected. “Net overseas migration numbers are being artificially boosted this year by the resumption of inward flows of international students and working holiday-makers,” Dr Kennedy said.

“This effect will diminish in subsequent years, when the usual inward and outward patterns of international student flows re-establish themselves.

“Coupled with broad softening in hiring demand, increases in net overseas migration should help to ease skill and labour shortages, particularly for the hospitality and retail sectors.”

During the Senate estimates hearing, Dr Kennedy rejected a suggestion Treasury was running a “big Australia policy” just as the Reserve Bank was trying to cool demand and reduce a 30-year high in inflation with aggressive interest rate hikes.

“We don’t have a big Australia policy,” he said in response to a question from LNP senator Gerard Rennick.

On the issue of a doubling in new student visas, the Treasury chief said: “There is an artificial dynamic at the moment. We are seeing some students return who weren’t here to finish degrees.”

Dr Kennedy said that “as to whether it puts pressure on rental markets and accommodation, more people clearly put pressure on rental markets and accommodation”.

Dr Chalmers told a Business Council gathering last Thursday the government was expecting a higher net migration inflow, due to more tourists, a faster return of international students, and as more Australians stay at home.

“Even with this big bounce in net overseas migration, we still haven’t caught up with what we lost in Covid and that’s why it will still take time to fill the gaps and the skills shortages that you’re all familiar with and we’ve talked about on multiple occasions,” the Treasurer said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout