Australia’s inflation drops to 7pc in March from 7.8pc in December

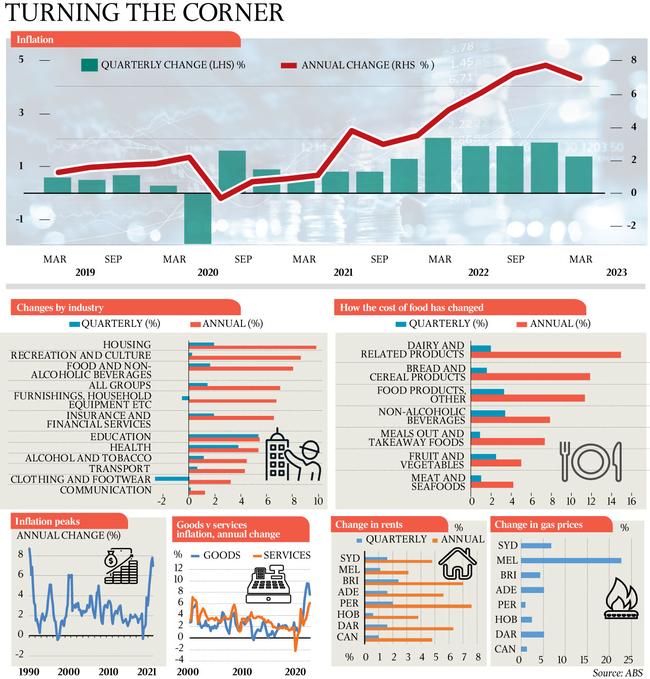

Inflation decelerated to 7 per cent in the year to March, even as surging rents and gas bills left the door open to another Reserve Bank rate hike.

Inflation decelerated to 7 per cent in the year to March, even as the fastest increase in rents since 2010 and surging gas bills at the start of the year compounded cost-of-living pressures and left the door open to another Reserve Bank rate hike next week.

With inflation peaking at a 30-year high of 7.8 per cent in December, economists are split over whether mortgage holders will be hit with another interest rate rise on Tuesday, after the RBA at its last meeting ended a series of 10 straight increases to hold rates at 3.6 per cent.

Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe, however, signalled that “some further tightening of monetary policy may well be needed” to bring inflation back to target.

As food price growth slowed from 9.2 per cent in the year to December to 8 per cent in the latest figures, Jim Chalmers said evidence of cooling cost-of-living pressures was welcome but inflation remained “unacceptably high”. “Even as these pressures ease a bit, we understand that Australian households and small businesses are still under the pump,” the Treasurer said.

Less than two weeks out from the May 9 budget, and after five Labor MPs broke ranks to call for a major boost to welfare payments, Dr Chalmers said “there will be cost-of-living relief in the budget and it will target the most vulnerable people, let me make that clear”.

He said he recognised the difficulty of living on benefits such as JobSeeker, but the best thing the government could do for those struggling with unemployment was to get more Australians into jobs. “My job is to weigh up all of the competing demands of the budget, and to do the right and responsible thing,” he said.

The quarterly increase of 1.4 per cent in the consumer price index was the lowest since late 2021, the Australian Bureau of Statistics figures showed, as discounting on furniture, appliances and clothes, alongside falling petrol prices, pushed goods inflation down to 7.6 per cent in the year to March, from 9.5 per cent in December.

Offsetting this were climbing prices for holiday travel, medical services, rents and restaurant meals, which drove annual services inflation from 5.5 per cent in December to 6.1 per cent in March, the biggest annual increase since 2001.

There was also a massive boost to household gas prices in the three months – including a 23 per cent jump in Melbourne as high wholesale gas prices flowed through to household bills.

The challenges facing renters also intensified in early 2023, with rental prices across the nation climbing by 4.9 per cent in the year to March and the most since 2010, the ABS data showed.

The largest annual rental increases were outside the country’s two largest cities, led by a 7.6 per cent jump in Perth and a 7 per cent rise in Brisbane. This compared to a 4.8 per cent increase in Sydney and a 3.1 per cent lift in Melbourne.

EY chief economist Cherelle Murphy said she expected a further rate hike to 3.85 per cent at one of the next two meetings.

“The Reserve Bank may not be convinced it will reach its forecast for trimmed mean inflation of 6.2 per cent by mid-year, given the ongoing strong demand for some services, the impact of a tight labour market, and renewed calls for cost-of-living relief on wages and rising rents,” she said.

The latest consumer price data came as a new SEC Newgate Mood of the Nation survey of 1200 voters revealed that 40 per cent of Australians were reporting financial difficulties.

While record energy price spikes are biting, the majority of Australians were most worried about grocery bills, followed by fuel costs, electricity prices, rent, mortgage payments and rising insurance premiums.

Amid a surge in concerns over housing affordability, the poll found 70 per cent of voters nominated the reduction of cost increases as an “extremely important” national priority.

Almost three quarters of voters said Australia’s net debt was too high, and that they were increasingly worried about the impact of higher levels of government spending on inflation.

Over the year to March, the largest drivers of the 7 per cent annual increase in the consumer price index was a 13 per cent lift in homebuilding costs, a 25 per cent surge in holiday and travel prices, and a 15.5 per cent rise in electricity bills.

The ABS data showed the biggest contributors to the 1.4 per cent quarterly increase in consumer prices was the 14.3 per cent jump in gas prices, a 9.7 surge in tertiary education costs, a 4.7 per cent increase in travel prices, and a 4.2 per cent lift in the price of medical and hospital services.

ABS head of prices statistics Michelle Marquardt said the quarterly rise in gas bills “was notable as prices increased in all eight capital cities, whereas typically only Melbourne’s prices are reviewed in the March quarter”.

Ms Marquardt said annual scheduled price increases, including for gas, health services and university courses, had underpinned the quarterly inflation result.

“Prices for medical and hospital services typically rise in the March quarter as GPs and other health service providers review their consultation fees, and the Medicare Safety Net is reset at the start of the calendar year,” she said.

“This year some private health insurance premiums also increased in January, adding to the price rise for medical and hospital services. Tertiary education fees are also indexed at the start of the year. This quarter additional strength was seen in tertiary education as changes in student contribution bands and fees introduced in 2021 as part of the Jobs-ready Graduates Package continued to flow through to the index.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout