Australian businesses in the dark about China’s new spy laws

Beijing’s anti-espionage law, which came into effect days before Hong Kong police put a bounty on two Aussies, has raised the risks for Australian companies.

Beijing’s new anti-espionage laws, which came into effect days before Hong Kong police put a bounty on two Australian residents, have further raised the risk Australian companies could have staff detained for what would be deemed ordinary business activities outside of China.

The brazen extraterritorial application of Hong Kong’s sweeping National Security Law in Melbourne and Adelaide on Monday has underlined just how serious Xi Jinping’s regime is about snuffing out behaviour it deems “anti China” and a threat to the Communist Party’s rule.

It shocked many Australians with dealings in China, a country already known for arbitrary detention. Concerns were already elevated over Beijing’s new anti-espionage laws, which took effect over the weekend.

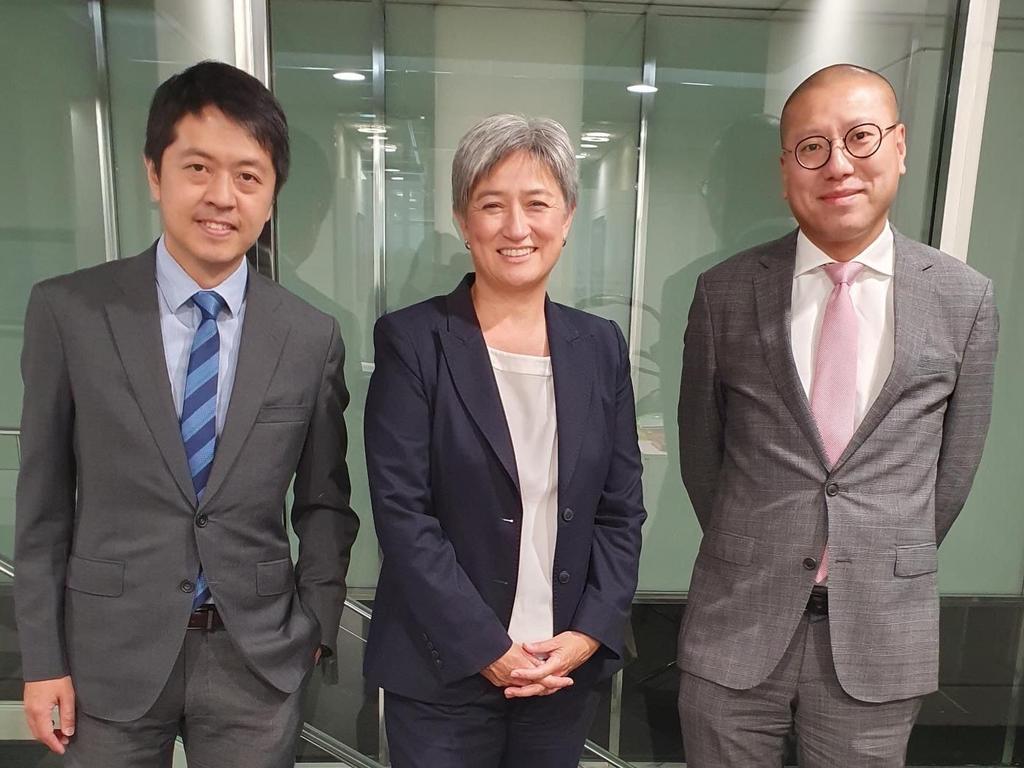

Unease about Beijing’s crackdown came as Foreign Minister Penny Wong said the Australian government was “deeply disappointed” by the news of the arrest warrants for Australian resident Ted Hui and Australian citizen Kevin Yam, who she met in Adelaide in January.

Mr Yam, who is now doing graduate studies at Melbourne University, said the supportive reaction he had received since the arrest warrant showed how far Hong Kong’s reputation had sunk.

“Normally if someone has an arrest warrant against them, to use an Australian term, you’re a bit of a dodgy bastard and it’s time to shun you,” he told The Australian.

“It says a lot about how far Hong Kong has fallen that people think that having a Hong Kong national security arrest warrant is a badge of honour.”

Three sources familiar with the situation said that Australia’s China-focused business chambers had not yet received specific briefings on the change from the Australian government.

One said the Australian system appeared to lack the capacity to follow the lead of America’s intelligence agencies, which have been stepping up their briefings of the risks for American businesses with a presence in China since April.

“They should be though. People are at risk of being detained for what used to be ordinary business activities,” the source said.

Some Australian companies have already adjusted their behaviour in China. “The smart, leading companies fully recognise that the risks have gone up an octave,” said a source who advises businesses with operations in China.

Australian security agencies routinely give briefings about risks to corporate security officers, CEOs and company directors.

A spokeswoman at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade would not comment on whether briefings had been given to Australian businesses and universities about China’s new anti-espionage laws. But she noted that Beijing’s updates “include provisions which appear to broaden the application of those laws”.

The Australian government’s Smartraveller website has warned since 2020 that “Australians may be at risk of arbitrary detention or harsh enforcement of local laws, including broadly defined National Security Laws”.

Australian citizens Cheng Lei, a state media television journalist, and Yang Hengjun, a democracy writer, have been in China’s penal system for years on vague espionage charges.

Mirriam-Grace MacIntyre, who leads the counterintelligence centre at the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, said the revised law expanded the definition of espionage without defining terms in a way that was “deeply problematic for private sector companies”.

American officials have been flagging to companies a State Department travel advisory in March urging Americans to reconsider travel to China, citing Beijing’s arbitrary enforcement of laws and use of exit bans blocking the departure of some US citizens.

“An executive’s decision to travel is their own personal decision,” said Ms MacIntyre. Her team wanted to ensure business travellers knew the risks.

Beijing has said that the rights of foreign businesses are protected under Chinese law. “As long as one abides by laws and regulations, there is no need to worry,” a Foreign Ministry spokeswoman said recently.

The bounties put on the heads of two Australian residents by Hong Kong cops are part of an ongoing effort by Beijing to police how China is discussed around the world. Days before the announcement by Hong Kong police, a Chinese diplomat attempted to stop the son of arrested Hong Kong media mogul Jimmy Lai from speaking at a United Nations event in Geneva.

Richard McGregor, senior fellow for East Asia at the Lowy Institute, said an Australian citizen had been charged by Beijing with a “thought crime”.

“The ‘Hong Kong Eight’ are essentially being accused of political crimes, and in some respects, old-fashioned thought crimes, for simply disagreeing with the territory’s National Security Law,” Mr McGregor told The Australian.

“It may look purely symbolic but it means someone like Kevin Yam, an Australian, will have to fly over many Asian countries which have extradition treaties with China before he can land somewhere safely,” he said.

On Tuesday, Hong Kong’s leader John Lee called on the activists to surrender to police.

“The only way to end their destiny of being an abscondee, who will be pursued for life, is to surrender,” the Hong Kong chief executive told reporters, adding they would otherwise “spend their days in fear”.

Australia is deeply concerned by reports of Hong Kong authorities issuing arrest warrants for democracy advocates, including those in Australia.

— Senator Penny Wong (@SenatorWong) July 4, 2023

Freedom of expression and assembly are essential to our democracy and we support those in Australia who exercise those rights.

Mr Lee was Hong Kong’s security boss when the National Security Law was imposed three years ago following Beijing’s instructions.

Hong Kong’s police force said a reward of HK$1m (AUD$191,800) would be given to people who provide information that would lead to the arrest of each of the eight accused.

Senator Wong on Tuesday said she had “deep concerns, about the national security laws in Hong Kong, and about their broad application.”

“Australia has a view about freedom of expression, we have a view about people‘s right to express their political views peacefully, and people in Australia who do so in accordance with our laws will be supported. We will support those in Australia who exercise these rights.”

Mr Yam, a Hawthorn AFL fan, worked as a commercial lawyer in Hong Kong for two decades before returning to Melbourne in 2022. The Hong Kong arrest warrant accuses the Australian citizen of “collusion”, citing meetings with “foreign government leaders” last November, an apparent reference to a trip he took to Canberra to meet federal politicians.

The University of Melbourne, which is taking its first delegation to China since the pandemic, did not comment on Mr Yam’s situation when asked on Tuesday.

Ted Hui, a former Hong Kong pro-democracy politician who sought political asylum in Australia in 2021 and now lives in Adelaide, was with Mr Yam on the November trip to Canberra.

The latest allegations against Mr Hui were prominently covered in China’s state media. He is accused of inciting secession, inciting subversion of state power and collusion with external forces, three of the four crimes in the National Security Law.

“It’s making it very apparent to the world that China is progressing towards more extreme authoritarianism,” Mr Hui said.

Opposition defence spokesman James Paterson, one of the politicians Mr Yam and Mr Hui met last November, said the Coalition was “gravely concerned” over the police bounties.

“This represents an unacceptable attempt to silence and intimidate critics of the Chinese government living in Australia, and further demonstrates the corrosive effects of the National Security Law to democratic principles and the rule of law in Hong Kong,” Senator Paterson said on Tuesday.

“Australia must always defend the fundamental values of democracy including freedom of speech and assembly and can never tolerate attempts to undermine the safety and freedom of Australians.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout