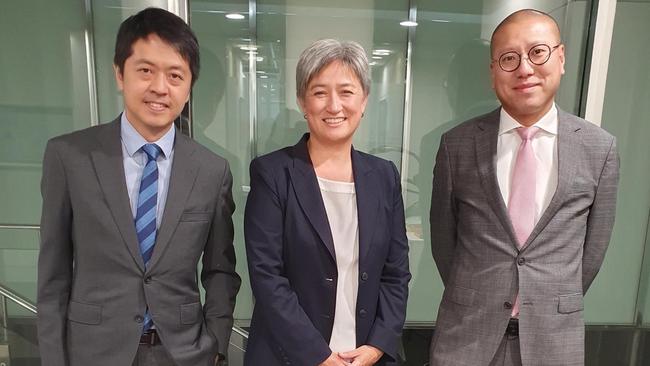

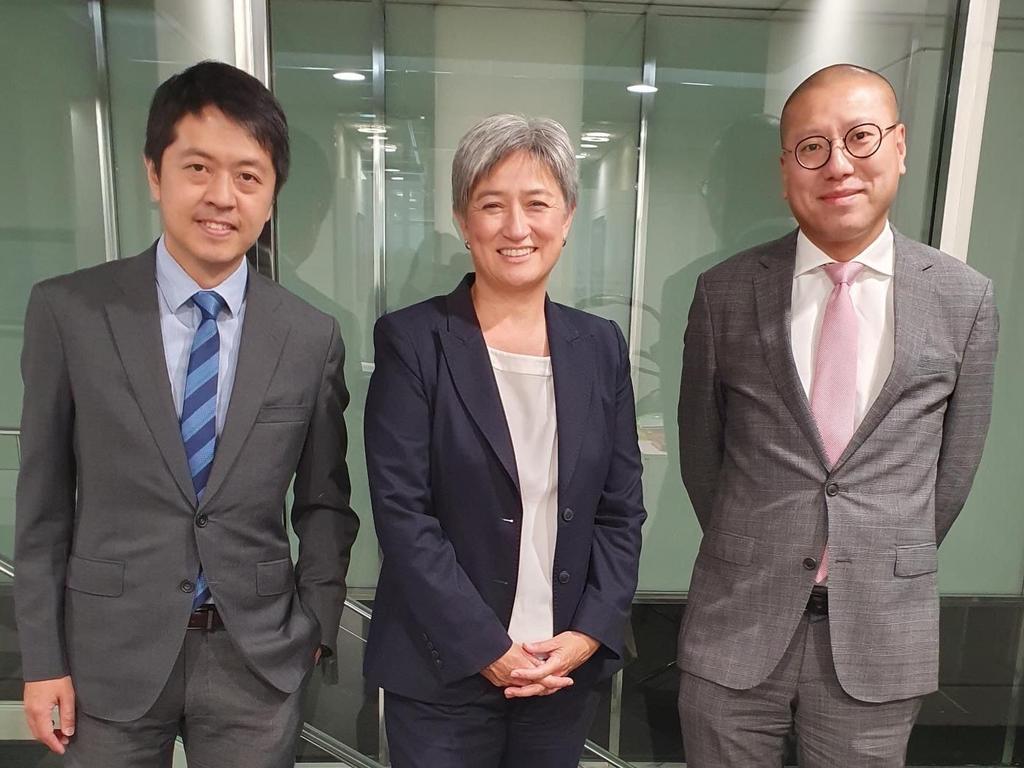

Hong Kong’s national security police also offered $HK1m rewards for information that leads to the capture of lawyer Kevin Yam, an Australian citizen, and former Hong Kong legislator Ted Hui, who lives in Adelaide.

The Foreign Minister expressed her “deep disappointment” at the Chinese actions, and reiterated that Canberra had long held deep concerns about the application of national security laws in Hong Kong.

Wong said: “I want to be very clear. Australia has a view about freedom of expression, we have a view about people’s right to express their views peacefully, and people in Australia who do so in accordance with our laws will be supported.”

Her comments make it clear the official Chinese actions represent an ugly effort to intimidate Australia, to intimidate the diaspora and ethnic Chinese community within Australia, and to intimidate the two democracy activists named.

The Australian government has an overwhelming operational responsibility now to make sure no agents of the Chinese government, and no one inspired by their effective call to persecution, can act against any Australians.

Wong recognises this in her further statement: “We have strong laws in relation to foreign interference. Our position on this is unequivocal. And any allegations about foreign interference will be investigated by the appropriate authorities.”

This is as brutal and naked a confrontation as Beijing and Canberra had at any time during the so-called wolf warrior diplomacy phase that Beijing indulged in for a couple of years.

Some Chinese national security laws explicitly apply to non-Chinese citizens and residents. They are extraterritorial in nature. They must also be seen in tandem with another new foreign relations law Beijing has recently enacted, which gives it the explicit authority to act against entities that behave in ways “detrimental to China’s interests”.

This law, like the National Security Law, is vague, sweeping and intimidatory.

These developments should cause the Albanese government to reconsider the path of rapprochement it is undertaking with Beijing.

For all the supposed new calmness in the relationship, Beijing still holds several Australians in its prisons on trumped-up political charges, it still enacts a range of trade boycotts against Australia and, as these actions make clear, it still attempts to intimidate and interfere with our politics.

While it’s sensible for the Albanese government to pursue a stable relationship with Beijing, while not compromising our national interests or values, it should not make a close relationship in itself an object of our foreign policy. Because in the end, Beijing wants to compromise and diminish key Australian national interests.

There is a dangerous political dynamic setting up now, because of the interaction of four factors. The Albanese government is seeking a stable relationship with Beijing. The Chinese government believes it played a role in getting ethnic-Chinese Australians to vote against the Morrison government.

The Left of the Labor Party is stridently opposed to AUKUS, the Quad and many elements of our alliance with the US.

And the Albanese government is subject to repeated, foolish attacks by Paul Keating.

The danger is the government will be tempted to get some critics off its back by prioritising “good relations” with Beijing, while if there are troubles in the relationship, no matter how egregious Beijing’s behaviour might be, a class of critics will flay the government for not succeeding in producing a good relationship.

This means Beijing effectively gets to reward or punish an Australian government within our own politics.

That’s bad, even dangerous.

The Albanese government should rethink this position and probably draw back.

Penny Wong was right to warn the Chinese government of the existence of strong foreign interference legislation in Australia, after Hong Kong authorities issued arrest warrants for two democracy activists now resident in Australia.