China’s charmless offensive loses hearts in free world

More than 15,000km away, former British chancellor of the exchequer Rishi Sunak had previously called for improved relations with China. But recently the Conservative prime ministerial hopeful has declared China and the Chinese Communist Party “the largest threat to Britain and the world’s security and prosperity this century”.

And in Taiwan, the increasingly pro-Beijing Nationalist Party chairman Eric Chu withstood pressure from China-friendly factions within his party to publicly support last week’s visit by US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

The evolving public positions of Marles, Sunak and Chu line up with the evolving attitudes of Australian, British and Taiwanese voters, who have become increasingly sceptical about China’s words, actions and intentions. Such scepticism has been observed across the free world.

University of Sydney China Studies Centre director David Goodman recently gave some advice to Beijing in an interview with the Global Times: “(A) publicity campaign, that’s what the US has had for some time through Hollywood, music, sports, and all kinds of ways in which it has a better reputation … China could encourage things like that if it wants to influence the government and public opinion.”

China repeatedly says it seeks to win hearts and minds around the world. But try as China might, it will likely struggle to succeed in the foreseeable future.

Let’s start with censorship. It has always existed in China, but for many years there was still relative freedom to produce thought-provoking entertainment content, so long as current politics was not directly touched on.

But, under Xi Jinping, censorship has tightened. Everything from imperial court intrigues and corruption dramas, to content alluding to societal ills, “girly men” performers, Tang Dynasty period costumes showing cleavage and karaoke songs that do not promote the party state’s notion of positivity and more became taboo.

In private, my entertainment industry friends and professional acquaintances in Hong Kong and China have complained about increasing difficulties in getting interesting content released in China.

Things that easily get past censors nowadays tend to be unquestioningly nationalistic works or bland plot lines where clean-cut good guys always win and similarly clean-cut bad guys always lose. Such dreary content is hardly going to take the free world public by storm.

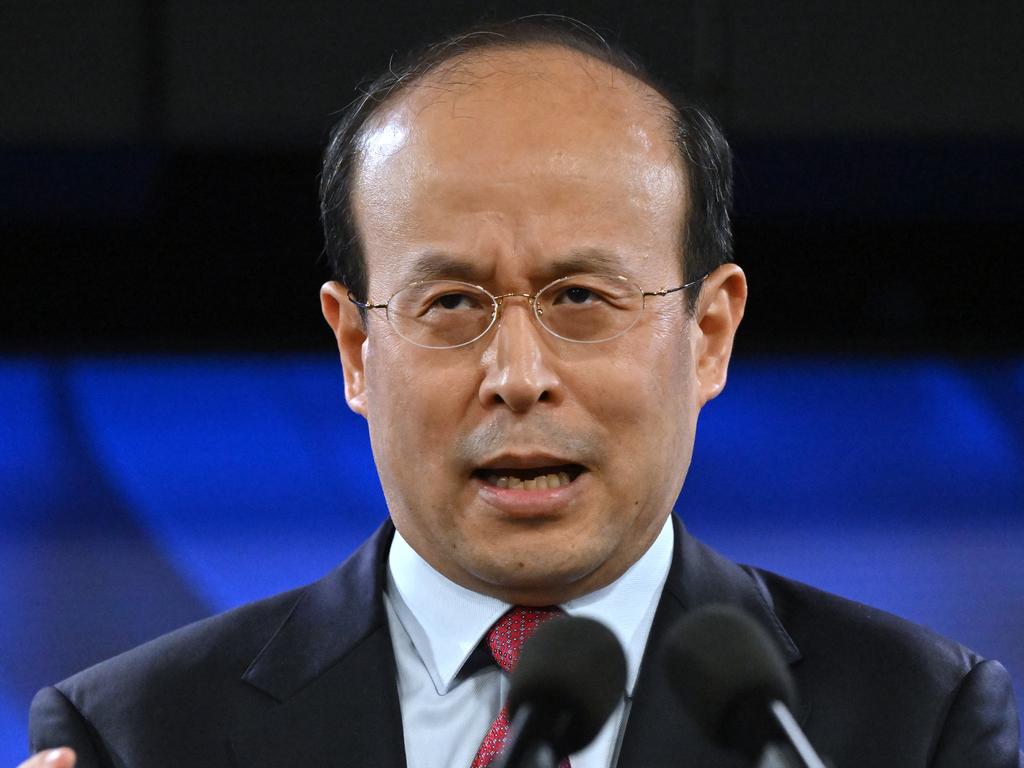

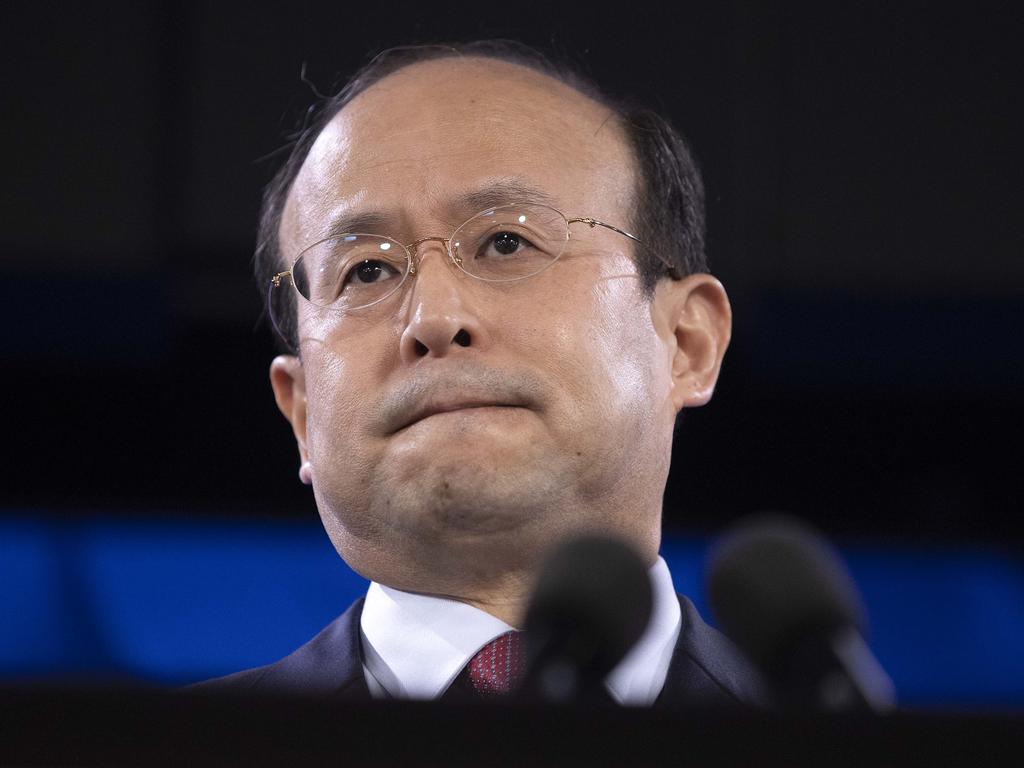

Further, as China’s domestic propaganda has become increasingly nationalistic in recent years, its messages to the world have followed suit. Threats such as those last week from China’s ambassador in France to subject conquered Taiwanese to “re-education” (and we know what that has meant in places such as Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong) is now the norm.

The strident, hectoring and threatening words and deeds from Beijing nowadays alienate public opinion in the free world, even in places such as Taiwan and Australia with economies that are closely linked to China. But Beijing cannot soften its face to the world without being considered weak by the nationalistic domestic populace.

Ultimately, China’s failure to win over hearts and minds in the free world reflects a fundamental weakness in its much-vaunted propaganda machinery. It is highly effective in China or in places where China-friendly strongmen censor narratives that run against China’s official lines. In such information and opinion bubbles, China can hone its messages for effective public charm offensives.

However, in places where China’s official lines can freely be questioned, its propaganda efforts fall apart. In the free world, China’s stridency merely seems nasty and insecure rather than strong and commanding. Its doublespeak and absurdities are exposed. Its unwillingness to brook dissent (unlike, say, America’s tolerance of protests around the free world against its policies) looks petty. Its acts of political, economic, cyber and military coercion appear downright nefarious.

China’s attempts at charm offensives in the free world may work on certain elites with direct vested interests, but they fail on the wider public. Charm offensives minus the charm are just, well, offensive. And when the public is offended, even free world politicians whose first instincts may be pro-China must bend to their public’s China-sceptic will.

Kevin Yam was a Hong Kong-based lawyer and pro-democracy activist. He now resides in Melbourne.

Defence Minister Richard Marles was once considered a friend of China. Now the Chinese party state media outlet Global Times declares that “Marles’s string of comments on the so-called China threat make it increasingly difficult to distinguish him from his extremely anti-China Liberal predecessor Peter Dutton”.