Cook rediscovered: white ghosts on coast

The great Maori chief Te Horeta called her supernatural. He wondered if her mighty sails were engineered by spirits.

The great Maori chief Te Horeta called her supernatural. He wondered if her mighty sails were engineered by spirits. He wondered if her great captain was more demon than navigator. Te Horeta was an old man in the mid-1800s when he told the early British settlers of New Zealand his great boyhood tale of how the Endeavour sailed into Mercury Bay in the eastern coast of the North Island’s Coromandel Peninsula.

In his biography, The Life of Captain Cook, the late and celebrated New Zealand historian John Beaglehole penned a stirring passage detailing Te Horeta’s great oral history.

The ship had come, it seemed a supernatural thing, and its men supernatural beings, for they pulled their boats with their backs to the shore where they were to land — had they eyes at the backs of their heads? They pointed a stick at a shag, there was thunder and lightning and the shag fell dead; the children were terrified and ran with the women into the trees. But these tupua, goblins or demons, were kind, and gave food: something hard like pumice-stone but sweet, something else that was fat, perhaps whale-blubber or flesh of man, though it was salt and nipped the throat — ships bread, or biscuit, salt beef or pork. There was one who collected shells, flowers, tree-blossoms and stones.

They invited the boys to go on board the ship with the warriors, and little Te Horeta went, and saw the warriors exchange their cloaks for other goods, and saw the one who was clearly the lord, the leader of the tupua. He spoke seldom, but felt the cloaks and handled the weapons, and patted the children’s cheeks and gently touched their heads. The boys did not walk about, they were afraid lest they should be bewitched, they sat still and looked; and the great lord gave Te Horeta a nail, and Te Horeta said Ka pai, which is ‘very good’, and people laughed. Te Horeta used this nail on his spear, and to make holes in the side boards of canoes; he had it for a god but one day his canoe capsized and he lost it, and though he dived for it he could not find it. And this lord, the leader, gave Te Horeta’s people two hand-fuls of potatoes, which they planted and tended; they were the first people to have potatoes in this country.

The oral histories of the Gweagal elders of Botany Bay speak of similar views from the shore as these strange Europeans sailed into the waters of their home. Shayne Williams, language and culture consultant, NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group, is a Dharawal elder who says those oral histories include thoughts that Cook and his men may have been ghosts and their great vessel a supernatural floating island. Some saw the sailors running up and down mast poles out at sea as scrambling possums.

The oral histories that indigenous campaigner Rodney Kelly heard as a boy about the arrival of James Cook were told from the perspective of the Gweagal warrior Cooman. That oral history speaks of April 29, 1770 as the day warrior Cooman courageously stood defiant in the face of Cook’s approaching marines who had sought no permission to enter a land Cooman’s people had occupied for 60,000 years.

Cooman, the oral history says, stood on the shores of Botany Bay with a younger man, instructing the Europeans to sail back to wherever it was they came from. Cooman was shot in the leg and dropped his shield as he ran for cover. Kelly acknowledges himself as a sixth-generation descendant of Cooman and is leading a campaign to have the Gweagal shield and spears collected by Cook’s men and housed in the British Museum and Cambridge University returned to his people in Sydney.

However, Williams has since stated in a report prepared by Cambridge University: “We do not know the individual identities of any of the Gweagal population of 1770, and we certainly cannot link any individual Gweagal person of that time to any of the spears that were obtained by Cook.”

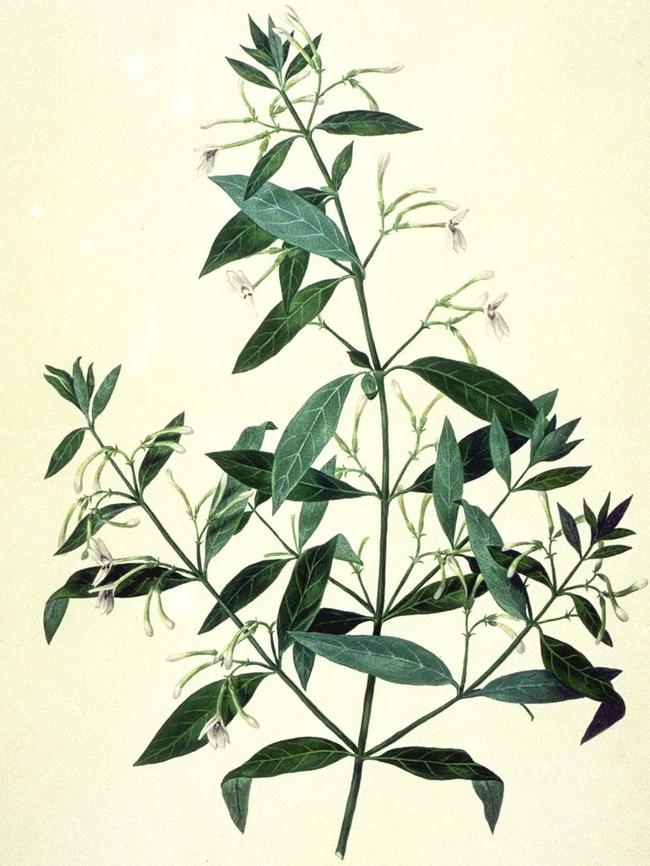

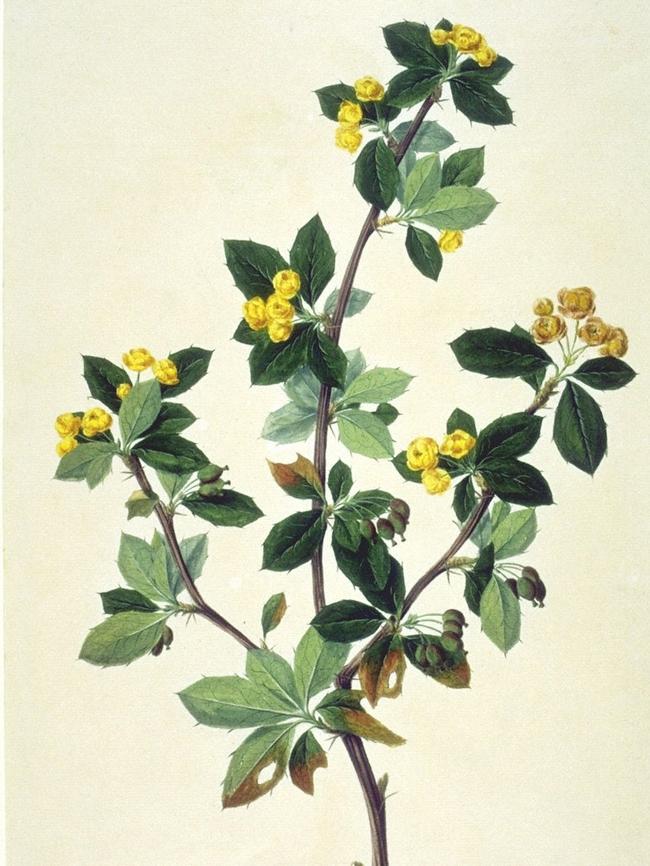

In a quiet corner of the National Museum of Australia, Ian Coates stares into a sketch of a banksia plant by Sydney Parkinson, part of Joseph Banks’s breathtaking Florilegium. Between 1771 and 1784, Banks underwrote a monumental project where he hired 18 engravers to create copperplate engravings from Parkinson’s countless Endeavour drawings of the 30,300 specimens Banks’s team found on their voyage through the Pacific, representing 3607 species in total, 1400 of which were unknown to science.

That banksia plant named in honour of the great botanist from Westminster, England, says Coates, was, of course, not unknown to the Gweagal people. Coastal banksia plants could be sucked for nectar, soaked in water to make a sweet and refreshing drink. The plants attracted honeyeater birds so they could be used as food traps.

“The view from the shore,” Coates says. “The story of Banks and Cook is such a fantastic story but the other part of that story, which we are now in a position to start telling, is the earlier knowledge of this material collected on that voyage. I think that’s one of the things we can look at as we approach the 250th anniversary. We can flesh out that side of the story.”

“The information is already there,” says the museum’s Cook specialist, Michelle Hetherington. “From Cook’s point of view, he’s interested in what is good to eat. He’s often asking the locals, ‘What’s fresh, what’s healthy, what’s nutritious?’ ”

Coates was co-curator of a National Museum exhibition last year named Encounters that temporarily displayed, among many indigenous objects held by the British Museum, the Gweagal shield many elders believe was the shield dropped by Cooman in that fateful moment of first contact.

“What sort of family history accounts are still out there about that moment?” he asks.

“I think it’s really important to describe Cook’s navigational feats through the Pacific, it’s an extraordinary story. But I think it’s also important to acknowledge the impact of those moments in Australia. It’s important to reveal the complexity of the situation and that space between the indigenous and the ship’s crew, to think about how that’s impacted on where we are today. The legacy of that moment.”

As Endeavour sailed north up the east coast of New Holland, the crew member who became the most adept at bridging that space between European and Aboriginal, says Hetherington, was the thoughtful artist Parkinson.

“Parkinson in particular spends his whole time on the voyage getting to know the indigenous people,” she says.

He’s courteous and kind and patient with the indigenous of the Pacific, especially, later, the inhabitants of far north Queensland.

“He must have been a very skilled person,” says Hetherington. “His nickname on board the ship was ‘Shy Boots’, which I think is just lovely. They called him ‘Shy Boots’ because, when everybody else was having lots and lots of fun in Tahiti he was holding back. He was reserved. He was Scottish. He was a Quaker.”

Parkinson was the first European artist to set foot on Australian soil, the first to draw an authentic Australian landscape, the first to paint the face of an Aborigine from direct observation. He takes the time to see the view from the shore. “Artists look at people in a different way,” Hetherington says. “He’s looking with the question, ‘Who are you? I’m looking at you.’ Who are these people as individuals? ‘I see you, not just a people.’ That was part of his great skill and he helped make these amazing word lists. He would sit with portrait subjects saying things like, ‘This is my nose, what do you call this? This is my arm, what do you call this?’ ”

Parkinson pens a vast vocabulary in his journal, indigenous Australian words for woman, man, father, son, hair, blood, head, bones, eyes, chin, arms, thumb, belly, the pit of the stomach, hips, anus, thighs, knees, legs, scars, toes, body sores, earth, dancing, swimming, paddling, yawning and a word for all those curious “leaping quadrupeds” the men will see bouncing around New Holland.

“Kangooroo,” he writes.

■ ■ ■

The Endeavour sails cautiously north from Botany Bay past another place of safe anchorage Cook names Port Jackson. Conscious of provisions and with his men naturally eager to return home after so long at sea, he doesn’t have time to investigate the wonders the area holds within it, including the most glorious harbour in the world that will one day be home to a pointy white opera house that will sparkle gold in the dropping afternoon sun.

The men eye the coast of New Holland as they go about their duties.

They see a paradise but they dream of home.

“Cook’s always keeping them busy,” says Hetherington. “Normally sailors worked 12 hours a day, but Cook instituted a system where men were on for eight and off for 16 hours.

“One of the things that makes scurvy worse is you’ve used up all your stores of vitamin C because you’re not getting enough sleep. The more pressure our bodies are under the more vitamin C we need.

“But there’s always cleaning to do, fumigating the ship, removing the bilge water, which really stinks. There are so many opportunities to learn from Cook. Men are learning astronomy, mathematics, drawing, all the things that will form part of their command when they’re promoted up the ranks. It’s like a school on board the ship.

“Then there’s all the readings to be done. Where are we? What’s the time? Have we worked out our position? ‘Mr Simmonds, have you checked your results against Mr Green’s results?’ It was busy, tiring, terrifying and very exciting.”

On May 9, 1770, Parkinson sees a rainbow and sings about it in print.

In the evening of that day we saw two of the most beautiful rainbows my eyes ever beheld: the colours were strong, clear, and lively; those of the inner one were so bright as to reflect its shadow on the water. They formed a complete semicircle; and the space between them was much darker than the rest of the sky.

Sailing well past what would become the fine city of Brisbane, on May 23, a frustrated Cook is distracted by a moment of ill discipline on board, potentially involving the New Yorker midshipman James Magra and Cook’s own keen-drinking clerk Richard Orton.

Last night some time in the Middle Watch a very extraordinary affair happend to Mr Orton my Clerk, he having been drinking in the Evening, some Malicious person or persons in the Ship took the advantage of his being drunk and cut off all the cloaths from off his back, not being satisfied with this they some time after went into his Cabbin and cut off a part of both his Ears as he lay asleep in his bed, the person whome he suspected to have done this was Mr Magra one of the Midshipmen, but this did not appear to me upon inquirey, however as I know’d Magra had once or twice before this in their drunken frolicks cut off his Cloaths and had been heard to say / as I was told / that if it was not for the Law he would Murder him, these things consider’d induce’d me to think that Magra was not altogether innocent, I therefore, for the present dismiss’d him the quarter deck and susspended him from doing any duty in the Ship, he being one of those gentlemen, frequently found on board Kings Ships, that can very well be spared, or to speake more planer good for nothing. Besides it was necessary in me to show my immedate resentment againest the person on whome the suspicion fell least they should not have stop’d here. With respect to Mr Orton he is a man not without faults, yet from all the enquiry I could make, it evidently appear’d to me that so far from deserving such treatment he had not designedly injured any person in the Ship, so that I do and shall all ways look upon him as an enjure’d man. Some reasons might however be given why this misfortune came upon him in which he himself was in some measure to blame, but as this is only conjector and would tend to fix it up some people in the Ship whome I would fain believe would hardly be guilty of such an acton, I shall say nothing about it unless I shall hereafter discover the Offenders which I shall take every method in my power to do, for I look upon such proceedings as highly dangerous in such Voyages as this and the greatest insult that could be offer’d to my authority in this Ship, as I have always been ready to hear and redress every complaint that have been made against any Person in the Ship.

Cook will later deem Magra innocent and the most likely offender, a midshipman named Patrick Saunders, will desert the ship.

The Endeavour moves slowly into what Cook is quickly realising is some of the toughest navigating he has had to do throughout the voyage, a tense maze of shoals and small islands the frumpy workhorse Endeavour splits through indelicately. Cook has no clue of the length and breadth of the greatest tourist attraction to the state of Queensland, a 2300km coral reef that will one day be seen by navigators of a different kind exploring outer space. What he calls an “insane labyrinth”, the world will come to call the Great Barrier Reef.

On the full moon night of June 10, Endeavour is sailing slowly but safely through the waters off far north Queensland, some 70km south of what is now called Cooktown. Cook descends to his cabin for a welcome night’s rest.

He slips into his drawers and rests his buzzing head. Shortly before midnight, he’s woken by the most terrifying sound a captain can hear at sea.

■ ■ ■

The indigenous politician Eric Deeral was born in 1932 at the Hope Vale Lutheran Mission on Cape York Peninsula, almost 50km northwest of Cooktown, in far north Queensland. Eric, who died in 2012, was the first Australian Aboriginal to be elected to state parliament.

He grew up with the oral histories of his people, the Guugu Yimithirr, swirling through his big and busy mind. These oral histories he passed on to his niece, Cooktown historian Alberta Hornsby, who has dedicated her life to providing indigenous perspective to Cook’s Endeavour journal. The view for her Guugu Yimithirr ancestors from the shores of Cooktown in June 1770 would have looked much the same as it does in any June, Alberta says.

“The southeast trade winds blowing like nothing else,” she says.

“Come June in Cooktown it just blows and blows and blows. And the rain comes. The miserable squalls.” Alberta would talk often with her uncle Eric about what it must have felt like for their people sitting by the fires on the shore and looking out to find the curious site of the British Royal Navy research vessel HMS Endeavour bobbing in the reef waters off their beloved home.

“My uncle and I discussed that moment at great length,” Alberta says. “He had heard the histories from his grandparents. There’s another aspect about Cook that added more to the story.”

She takes a deep breath.

“We believe our people were waiting for their ancestors to return,” she says. “It was believed that when our ancestors died their spirits travelled to the east and when they returned they would come from the west. But their spirit would have been changed when they returned and they would return with white skin and they would come with the hand of plenty and they would hunger no more. My uncle and I would talk about this story.”

And Alberta would wonder what her ancestors made of the British colours flapping in those southeast trade winds.

Did they wonder, like the young Maori boy Te Horeta did back in New Zealand, if these visitors were made not of flesh and bone but of something supernatural? Did they consider these men in heavy clothes and hats the spirits of their ancestors? And if they did consider them thus, did they wonder why on earth their mighty ship was sinking?

Return to the Cook Endeavour series page here