Cook rediscovered: Endeavour believed to be in watery Rhode Island grave

Research has narrowed down the location of Cook’s scuttled ship to 1000sqm, and another dive is starting next week.

It has to be seen through the eyes of the young. Nicholas Young. The youngest on board. The boy will go on to become a servant to Joseph Banks. He’ll join the great botanist in 1772 on a journey to Iceland. But there’ll be no greater story he will tell in his lifetime than the one about how he joined Lieutenant James Cook on his first great epic voyage of discovery. He leans out from Endeavour’s masthead and pierces his eyes to catch a glimpse of England. The boy has made it home.

On July 12, 1771, young Nick watches Endeavour’s storm-bashed and sunbaked ribs and rails sail gently into the port of Dover. She carries weary but elated men, illuminated men. She carries objects and artefacts and great specimens to be celebrated and written about for the next 250 years. But most of all, she carries knowledge. New insights into navigation, mathematics, geology, astronomy, map-making, botany, languages. She carries new strategies to manage men, to survive at sea, to cross entire oceans into new hemispheres of thinking. She carries a whole new world.

Far behind her crew is an invisible string of adventure stretching back down and around the southern hemisphere, passing through cyclones and deadly storms and coastal trees etched with their names and the sounds of native tribes telling stories of their ghostly arrivals. And scattered like thumb tacks on a world map are the buried bodies of their friends, the men who didn’t make it home — men like Zachary Hicks and Sydney Parkinson and Forby Sutherland — the brave men who dared to sail through all those blue and black seas with their great Captain Cook.

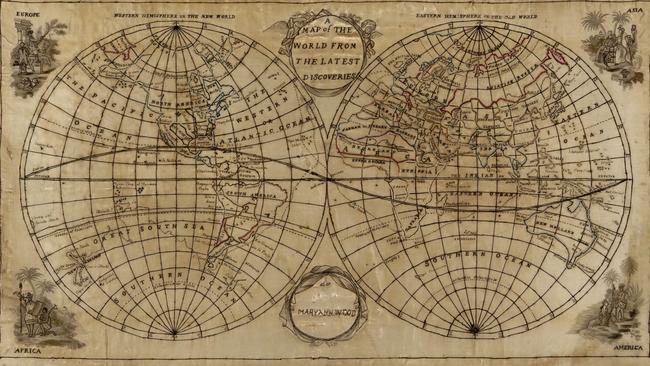

In a strictly off-limits temperature-controlled room inside the National Library of Australia, historian Martin Woods, the library’s curator of maps, casts his eyes over a table of priceless world maps from the 18th century. He studies a late-1700s map titled “Map of the World on a Global Projection Exhibiting Particularly the Nautical Researches of Captain James Cook”.

“Look at what he did,” Woods gasps. The map is split into two circular halves, two sides of the world, the right side being Europe, Asia and the Americas, the left side being Cook’s vast Pacific. Woods waves his hands over the whole left side of the map. “He expanded the globe by that much. It’s a completely different world by the time he’s done.”

Nigel Erskine of the Australian National Maritime Museum says: “Even in the places he was seeing nothing he was seeing something. If you’re seeing nothing you’re able to put on your chart that there is no land in that area. To find nothing was adding something.

“Basically, after his third voyage, Cook put everything on the map and there wasn’t a lot left for others to do.”

Erskine has dedicated much of his recent life to academically tracing the fate of Endeavour after Cook.

“Dr Kathy Abbass (from the Rhode Island Marine Archeology Project) announced in 1999 that she had found evidence that the Endeavour — renamed the Lord Sandwich — had been part of this fleet of vessels scuttled in 1778 in Newport Harbour, Rhode Island, to repel a French attack in the town during the American Revolutionary War,” he says.

“And in the last couple of years I decided that somebody needed to do the basic research into this. In 2014 I spent two weeks in London in the National Archives and the library at Greenwich and the British Library going through all the records. I was able to find the documentation which showed that ultimately she was one of five vessels scuttled at Rhode Island.”

More significantly, Erskine has since been able to narrow the final resting point of the most important vessel in Australian history down to a target area of roughly 1000sq m.

“There was a place called Goat Island, which sort of sticks off the mainland in Newport Harbour, and north of that there was a little fortification called the North Battery. The Endeavour was one of five vessels scuttled between the northern tip of Goat Island and the North Battery, so you’re talking about an area of about 1000m and you’re looking at depths of around 40ft.

“What my research has done is it has said, ‘Look, if you’re interested in finding Endeavour, then this is the area that we should be focused on.’ So the Rhode Island Marine Archeology Project people have taken that on board.”

Erskine says Abbass’s team will commence its next potentially revelatory major research dive on September 11.

“I feel we’re close,” says Erskine, who has visions of Australia marking the 250th anniversary of Cook’s landing in Botany Bay in 2020 by gazing upon the actual remains of the Endeavour recovered from Newport Harbour. “We’re hoping that we could positively identify the vessel, say, ‘Yes, the remains are there’, and be able to say it with hand on heart, having done all the research and archeology by 2020.”

If it is found, says Erskine, it will be a hugely significant archeological moment connected to the foundation stories of both Australia and the US. The next debate after that will be a complex one: who gets to keep it?

Cook’s dogged old coal boat of discovery may be more intact than one might think after sleeping for 240 years at the bottom of the sea.

“We’ve seen other vessels that were scuttled in Newport Harbour and there’s quite extensive remains of timber down there,” Erskine says. “These vessels were built from great big bulks of oak. If they’ve been covered by the mud and things then that timber tends to still remain, not necessarily as hard as it was originally; it tends to get quite porous and be a bit spongy but still, if the Endeavour is still down there, then I would expect to find, certainly, part of the keel and the ribs off that keel and maybe some of the lower planking.

“We could easily find cannon. We could find some of the iron ballast and because it was scuttled in relatively quick time, you might expect there were things on board that they didn’t have a chance to get off … So we might find ceramics, things like plates and jugs and cups and things. Those things survive for centuries underwater.”

Erskine has made five research dives himself since 2005 in Newport Harbour. “It’s far from an ideal site,” he says. “Rhode Island, and Newport in particular, is a bit of a mecca for boats. You have to be aware of recreational boaters and lobster fishermen and the other people around the site. Often commercial fishermen don’t like the fact you’ve occupied a part of their harbour where maybe they’ve got lobster pots down there. The lobsters themselves like to burrow down among wrecks so you have to be careful where you put your hands because they have one big claw which can crush your finger.

“Then there’s a very big tidal movement. Twice a day the tide moves in and out, so visibility is generally not great, maybe a visibility of three, four metres, whereas, when we’re diving in the Coral Sea you’re talking about 30m. Diving in the Coral Sea is like diving in gin. Diving in Rhode Island is more like diving in sewage.”

But the adventure of it draws him back. It’s the same thing that drew James Cook back to the sea on all those voyages after Endeavour. “It’s filled with wonder,” he says. “It’s modern exploration. You’re always wondering what you’ll find next.”

■ ■ ■

There’s a beautiful passage in Cook’s journal where he briefly ponders the wonder and compulsions in the life of an 18th-century explorer of uncharted worlds — the thrill of wondering what you’re going to find next. He wrote it in mid-August 1770 after surviving yet another hellish ocean battering — maybe the worst he would ever face — in the Great Barrier Reef in which he was saved by “nothing but providence”. “The same sea that washed the sides of the Ship rose in a breaker prodigiously high the very next time it did rise so that between us and destruction was only a dismal Vally the breadth of one wave,” he writes. “All the dangers we had escaped were nothing little in comparison of being thrown upon this Reef where the Ship must be dashed to pieces in a Moment, a Reef such a one as is here spoke of is scarcely known in Europe, it is a wall of Coral Rock rising all most perpendicular out of the unfathomable Ocean.”

Rattled and alive, and awed by God and sea, Cook gathers his thoughts the following day and writes some of the most powerful words he’s ever written. It’s one of the few times the normally businesslike and humble leader owns his courage and his commitment.

Was it not from the pleasure which naturly results to a Man from being the first discoverer, even was it nothing more than sands and Shoals, this service would be insupportable, especially in far distant parts, like this, short of Provisions and almost also every other necessary. The world will hardly admit of an excuse for a man leaving a Coast he has unexplored he has once discover’d, if dangers are his excuse he is than charged with Timorousness and want of Perseverance and at once pronounced the unfittest man in the world to be employ’d as a discoverer if on the other hand he boldly incounters all the dangers and obstacles he meets and his unfortunate enough not to succeed he is than charged with Temerity and want of conduct.

The former of these aspersions cannot with Justice be laid to my charge and if I am fortunate enough to surmount all the dangers we may meet the latter will never be brought in question. I must own I have ingaged more among the Islands and shoals upon this Coast than may be thought with prudence I ought to have done with a single Ship and every other thing considered, but if I had not I should not have been able to give any better account of the one half of it than if we had never seen it, that is we should not have been able to say wether it consisted of main land or Islands and as to its produce, that we should must have been totally ignorant of as being inseparable with the other.

Words too long for a song or sea shanty, much less a T-shirt or Twitter feed. Words written only for history.

In the off-limits maps room of the National Library of Australia, Martin Woods holds up a small yellow box made of shark skin not much bigger than the kind of box that would hold a diamond ring.

The box dates back to the year 1790 and has a small yellow lid that flips open to reveal the entire world.

“It’s a pocket globe,” Woods says. A prized possession cooler than an iPhone in the 18th century.

“Look,” he says, spinning the marble-sized globe inside the box to the perfectly mapped continent of Australia. “It’s a complete world.”

He spins the globe again and stops on a series of words etched over Hawaii. A date: February 14, 1779. “It’s a world that recognises the death of Captain Cook,” Woods says.

It’s the only significant event from world history the pocket globe’s makers thought to mark on it.

Return to the Cook Endeavour series page here