Cook rediscovered: Miracle on the Great Barrier Reef

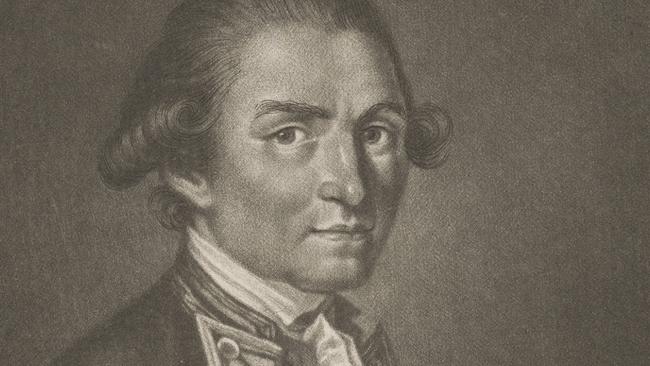

James Cook’s first encounter with Aborigines, and the Great Barrier Reef, came close to ending in disaster.

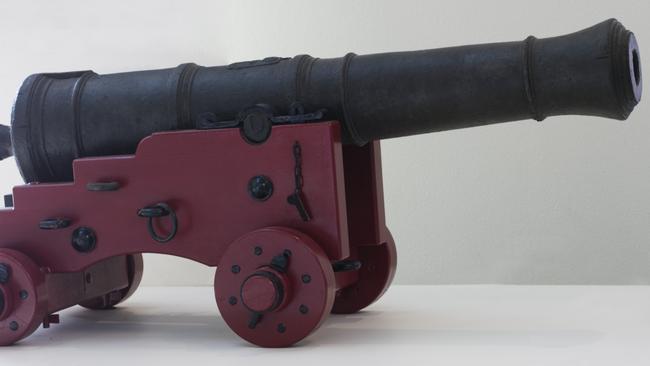

She can hear the cannon blasting. She can see the worn, callused hands of Captain Cook’s men touching it. She can see where it sat on the Endeavour before it was desperately heaved overboard into the night-time waters of Endeavour Reef to be found 200 years later by researchers from the American Academy of Natural Sciences. Cook historian Michelle Hetherington draws a long breath. There’s no story she can tell more thrilling than the story of the black iron cannon she stares at now in a soft-lit room inside the National Museum of Australia.

“This is our actual history sitting in front of us,” she says. “Who touched it? They may have all touched it! This is our link to that voyage in the 18th century.”

June 10, 1770. A fat-bottomed coal carrier sails awkwardly along the coast of far north Queensland under a full moon.

“Cook’s retired for bed,” Hetherington says. “He’s in his drawers, according to Sydney Parkinson. They’re doing a running survey along the coast. Nobody really knows the Great Barrier Reef is there. It’s about 11 at night. The men are sounding the lead, testing the depth as they’re going and, suddenly, it goes from 20 fathoms to five in seconds. And, ‘Booooooooom’. They bang into a coral outcrop of the Great Barrier Reef.”

The banshee howl of timber splitting. The Endeavour jolts to a stop. Men look overboard to find broken planking floating atop the water. A hidden reef of sharp coral has stabbed a sickening hole in the underside of what, right now, looks certain to become the most famous vessel to ever rest at the bottom of Endeavour Reef.

The men see death. The men see two years of bold and brave exploration and groundbreaking scientific research lost to the Pacific Ocean that’s pouring into Endeavour’s hold.

“The great fear when you hit something like that is that your ship is going to break up and you’re all going to drown,” Hetherington says. “There were not enough boats to take everybody to the shore. These sailors weren’t encouraged to learn to swim. Most of them couldn’t swim. Normally when something like this happens the crew mutiny. They’d break open the rum, they’d get completely drunk, and the theory is we might as well ease our passage out of this world. If your ship’s going down, better to go down quickly than struggle along. We’ll just have a bit of fun before we go.”

Hetherington shakes her head in awe.

“But they don’t do that.”

Something magical happens that night on Endeavour Reef. Cook’s men unite. To the face of certain death, they raise a combined middle finger.

Cook rushes to the deck, still in his nightshirt. He barks orders to his men in clear, sharp sentences. He calls for calm and effort. Robert Molineaux assesses the damage from a small boat. Men of all ranks rush to the wood pumps to lower the rising water levels in the hull.

“Immediately, they all move into action to save the ship,” Hetherington says. “They pull down the sails, they row anchors out from the boat at two separate points attached to heavy rope so that they would have leverage points. There were four wooden pumps on board and only three of them worked and everybody on board — including Joseph Banks, who was a gentleman and part of a private party — took their turn manning the pumps. They all work in unison for Cook. They’re a real team.”

Cook instructs the men to lighten the ship.

“There are 10 of these cannon on board and six of them go straight overboard along with tonnes of iron ballast pigs.”

Decayed stores go over. Oil jars and hoops and casks go over too.

Wise Banks is heartened by the efforts of the men but he can’t shake his fear of certain death.

All this time the Seamen workd with surprizing chearfullness and alacrity; no grumbling or growling was to be heard throughout the ship, no not even an oath (tho the ship in general was as well furnishd with them as most in his majesties service). About one the water was faln so low that the Pinnace touchd ground as he lay under the ships bows ready to take in an anchor, after this the tide began to rise and as it rose the ship workd violently upon the rocks so that by 2 she began to make water and increasd very fast. At night the tide almost floated her but she made water so fast that three pumps hard workd could but just keep her clear and the 4th absolutely refusd do deliver a drop of water. Now in my own opinion I intirely gave up the ship and packing up what I thought I might save prepard myself for the worst.

The most critical part of our distress now aproachd: the ship was almost afloat and every thing ready to get her into deep water but she leakd so fast that with all our pumps we could just keep her free: if (as was probable) she should make more water when hauld off she must sink and we well knew that our boats were not capable of carrying us all ashore, so that some, probably the most of us, must be drownd: a better fate maybe than those would have who should get ashore without arms to defend themselves from the Indians or provide themselves with food, on a countrey where we had not the least reason to hope for subsistence.

But stout Cook has a sailor’s faith. He believes in the sea. He believes in his men. He believes in his ship. He believes in himself. He believes in providence.

“They had this idea of providence,” Hetherington says. “I don’t know that Cook is particularly religious but he had this idea that they were being looked after. That they had great fortune, possibly due to some superior God-like being — providence.”

As night turns to day turns to night, and the mighty vessel remains lodged on the reef, Cook calls on his men to pump faster and work, work, work towards a high tide that might just enable the men to winch the vessel off the reef. As the tide rises, Cook calls on his men out on the full boats to pull hard on their oars until the winch ropes are so taut they might snap clean away from Endeavour. About 10pm, she moves.

“They manage to winch the ship off the coral,” Hetherington says.

The men rejoice. Their darkest hour is their finest. Banks writes:

During the whole time of this distress I must say for the credit of our people that I beleive every man exerted his utmost for the preservation of the ship, contrary to what I have universaly heard to be the behavior of sea men who have commonly as soon as a ship is in a desperate situation began to plunder and refuse all command. This was no doubt owing intirely to the cool and steady conduct of the officers, who during the whole time never gave an order which did not shew them to be perfectly composd and unmovd by the circumstances howsoever dreadfull they might appear.

“I dived in the Endeavour Reef in 2009,” says Nigel Erskine from the Australian National Maritime Museum. “There is still material there on the reef you can identify as being part of Endeavour. Then you look out at how far off the coast he was, you can see a distant mountain range, and you just think, ‘God, that guy was lucky that he got off that reef’. If he doesn’t, everything is lost. Chances are, Banks dies. It’s Banks who later becomes the ambassador for a British colony in NSW. Who would have done that if he hadn’t? If Cook doesn’t get off that reef, there’s a whole range of dominoes that do not fall.”

It takes Cook and his men six days to pull a dangerously wounded Endeavour delicately to shore.

“Even though they can see the shore, and they’re not that far away, they have to carefully nurse the ship along,” says Hetherington. “They can’t put up too much sail because it could tear the ship apart if there’s too much force put upon it. But they do this thing where they make what’s called a fothering sail. They lay a sail on the deck and they fill it with all the dung from the sheep and animals on board and the straw from their bedding and used up bits of rope to make a gooey sticky mess that they fold over like a bandage and then they fling it over the ship to bring it up to the point where they know where the hole is. The pressure of the water pushes it into the hole like a plug and with that they manage to limp to shore. Extraordinary.”

Hetherington makes a grave face.

“Of course, they then had no idea what they would see on shore.”

■ ■ ■

The Guugu Yimithirr people call it Waalumbaal Birri, the Endeavour River, near Cooktown, far north Queensland, where Cook spends almost seven weeks repairing his ship on the river’s protected south bank. Cook doesn’t know it yet but providence is at play again.

“They’re at the mouth of the Endeavour River,” says historian Alberta Hornsby, a Guugu Yimithirr woman from Cooktown. “Fortunately for them, they bring the boat in at the south bank of the river. Fortunately for them, this is a neutral zone. That particular clan land is part of the land that is shared and used by surrounding clan groups for ceremonies and sharing of resources, for example, during flying fox season. This is where the people from five surrounding clans could meet and come to Cooktown to share in that resource. This is a place where disputes are settled and where women gave birth. A special place.”

If there is one place for strangers to respectfully land along this long and rugged coast, then Cook has miraculously landed upon it.

“They beach the ship on the banks of the river and it’s laid over on its side,” says Hetherington. “When they turn the ship over there’s this giant boulder of coral still jammed into the hole.”

Cook writes:

… the rocks had made their way thro’ four Planks, quite to and even into the timbers and wound’d three more. The manner these planks were damaged or cut out as I may say is hardly credable — scarce a splinter was to be seen, but the whole was cut away as if it had been done by the hands of Man with a blunt edge tool — fortunately for us the timbers in this place were very close other wise it would have been impossible to have saved the ship and even as it was it appear’d very extraordinary that she did not made no more water than what she did — A large piece of Coral rock was sticking in one hole and several pieces of the fothering, small stones, sand had made its way in and lodged between the timbers which had stoped the water from forceing its way in in great quantities.

“They feel this was an act of providence, that the ship had taken the coral with it,” Hetherington says. “Otherwise the hole would have been so big they would have gone down. They now empty the ship out and start chopping down trees to make the timber they’ll use in repairs. They’ve got two things on their mind. Who lives here and are they going to be safe?

“It takes them 10 days to fix the boat but they stay for 48 days,” says Hornsby. “Our people are observing them the whole time but it’s not for about a month that our people make contact with Cook.”

Some oral histories passed down to Hornsby say the Guugu Yimithirr people may have believed Cook’s men were the spirits of departed ancestors returned in white skin, as foretold in shared stories. “I think that’s one of the most important things that adds to Cook’s success in that first voyage,” Hornsby says. “They were shipwrecked far from home. There was no way out for them, but they did not have the added burden of aggressive natives. What happened on that river was a cultural exchange. It was a deep insight into two cultures meeting for the first time.

“Of course, Cook’s men came with gifts and all the gifts were useless, nails and cloths and everything, because all our people were interested in was the colour of their skin. All they were interested in was making Cook’s men strip off so they could examine them and in the journals Cook says he lets them do what they need to do.”

Some Guugu Yimithirr oral histories, says Hornsby, suggest “our people were wondering why these white people were not recognising them as their relatives”.

“They were still waiting for their ancestors to return.”

■ ■ ■

Banks and Solander explore the area for specimens. The many ill crew on board have time to recuperate. Provisions for the long journey home are found in the food-rich land. It’s here that Parkinson learns of the intrepid “kangooroo”, which Hornsby’s people say he misspelled from the native “gangurru”.

“It’s only the second time they’ve spent any time on the Australian continent,” says Hetherington. “And they have this really remarkable relationship with the local people who, to this day, consider that first meeting as the first act of reconciliation between black and white on Australian territory.”

It’s here that the Guugu Yimithirr record what Hornsby considers a beacon moment for indigenous and non-indigenous relations in Australia. The oral history says Cook’s men collected 12 turtles from a breeding area that formed part of a sacred storyline connecting land and sea.

“They were taken from a part of the reef that was sacred to the clans who had exclusive use of those waters,” Hornsby says. The locals demanded that two of the turtles be returned. This request was refused, says Hornsby, upon which a brief conflict occurred in which a local man was struck in the shoulder by British musket fire and several spears were removed from increasingly aggravated natives.

“But this was sacred ground and our men could not do anything that could cause blood to fall on it,” she says.

“The reconciliation was taken by a little old man and he came forward out of the bush while Cook and them was resting, he came forward carrying a spear with a broken tip and he performed a ritual where he drew sweat from under his arms and he threw the sweat in the air, indicating that he was calling on his ancestors to recognise him and to help him with this situation, to make amends for the conflict that had just happened. He came forward and Cook couldn’t understand anything he was saying but he knew, by the little old man’s actions, what was actually happening.” Cook writes:

After some little unintelligible conversation had pass’d they lay down their darts and came to us in a friendly manner . We now returned the darts we had taken from them which reconciled every thing.

The events surrounding Cook’s time on Endeavour River have been re-enacted annually in historic Cooktown for almost 60 years. The re-enactment script was rewritten in 2008 to better represent the perspective of the Guugu Yimithirr people. To better represent the view from the shore.

“We try very hard now to tell the story of two cultures and one people,” Hornsby says. “And there’s all these people working together now, you know, from a little place like Cooktown. It’s that reconciliation.”

Before he died in 2012, Hornsby’s uncle, Cooktown politician Eric Deeral — the first Australian Aborigine to be elected to state parliament — spoke of his admiration for Cook’s diplomacy. The captain seemed to put people before politics. He judged events by the information he had before him, surveyed right and wrong with the same balanced eye he cast across the Australian coastline.

“I’m 62 years old,” Hornsby says. “I was born on a mission, a place set up to take care of a dying race. For a lot of people, that great journey of Cook’s represents the beginning of so much destruction for our people that lasted right up to the 1960s.

“But then I look around Australia and I see today that we have so much strong Aboriginal culture and we have so much beauty and interest and connection within Australian society. Our people are strong and so resilient and I see so many young people carrying on our traditions and we still have so many strong elders in the 21st century and every effort is being made to maintain our language. The stories are still in our heads and our hearts.

“If only we took that diplomacy that was shown in Cooktown into the future. Cook did things without argument. He didn’t argue about those spears. He just gave ’em back.”

■ ■ ■

Early August, 1770, and Cook is anxious to put back to sea.

“So they’re about to go and Cook climbs up a place called Grassy Hill in Cooktown,” says Hetherington.

Looking out to the Pacific, he hopes to find safe passage north in the direction of the East Indies.

“But he’s appalled to find the Great Barrier Reef stretching the whole way up like a labyrinth in front of him,” says Hetherington.

His dreaded “insane labyrinth” is not finished with him yet.

But he does not baulk. He sails on. On August 22, 1770, he lands on a small island at the extremity of the Cape York Peninsula. This island will be called Possession Island, where Cook claims the east coast of Australia for Great Britain.

Having satisfied myself of the great Probabillity of a Passage, thro’ which I intend going with the Ship and therefor may land no more upon this Eastern coast of New Holland and on the Western side I can make no new discovery the honour of which belongs to the Dutch Navigators and as such they may lay claim to it as their property but the Eastern Coast from the Latitude of 38° South down to this place I am confident was never seen or viseted by any European before us and therefore by the same Rule belongs to great Brittan Notwithstand I had in the Name of his Majesty taken posession of several places upon this coast I now once more hoisted English Coulers and in the Name of His Majesty King George the Third took posession of the whole Eastern Coast from the above Latitude down to this place by the Name of New South Wales together with all the Bays, Harbours Rivers and Islands situate upon the same said coast after which we fired three Volleys of small Arms which were Answerd by the like number from the Ship.

He sails on with haste, pushing his bruised and battered coal boat further and further into the unknown because there’s another place he desperately wants to find. A place truly like no other.

Home.

Return to the Cook Endeavour series page here

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout