Captain Cook’s Endeavour: long voyage to Terra Australis

It was a courageous captain who set out with secret instructions to find the great unknown southern continent.

She has to be seen through the eyes of the young. Nicholas Young. The cabin boy they call “Young Nick”, the youngest of Cook’s crew. Hope in his heart, heart in his throat. He’s 11 years old and before he reaches his teens he will see death and glory, lust and violence, and a southern world that exists only on the latitude of his wildest dreams. But for now all he sees is her.

The ship they call Endeavour, anchored in the dockyard waters of Plymouth, on the south coast of Devon. August 26, 1768. She fills the boy’s senses. The adventure in her. The feel of her wood beneath his soft fingers. The smell of salt and sea in her ribs and rails.

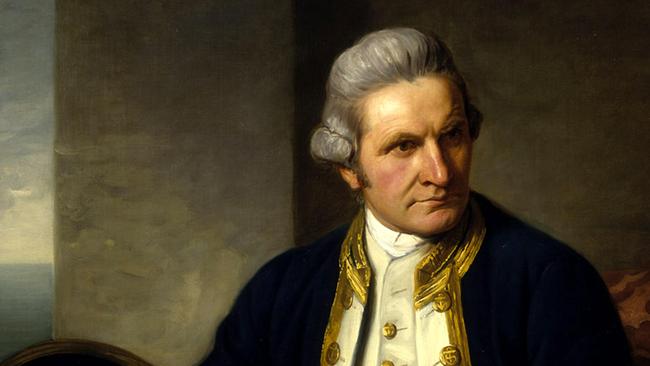

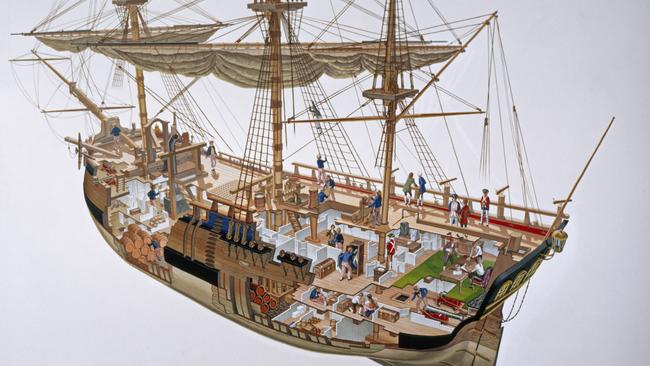

She’s a product of Yorkshire, like the great captain who’ll make her famous. And like that towering 6ft-tall figure, James Cook, she’s all business. No figurehead on the prow. No useless decoration. A coal boat, more functional than fancy. Thirty-two metres long, only 9m across the beam. A broad bow, a square stern, a frumpy body and a flat bottom.

Her captain — who cut his 40-year-old sailor’s teeth plying coal along the English coast — sees things in her others can’t see. He sees reliability, a shallow draught that will allow him to manoeuvre close to shore in only a few fathoms of water, like the barks that carry coal across the North Sea into London. She won’t sail gracefully but she’ll sail far.

Ten four-pounder cannons for protection, 12 swivel guns fixed to the quarterdeck, sides and bow. A deep cargo hold carrying 18 months of provisions: 20 tonnes of biscuits and flour, 1200 gallons of beer, 1600 gallons of spirits, 4000 pieces of salted beef, 6000 pieces of salted pork and 7860 pounds of sauerkraut because the deep-thinking captain is convinced that potent fermented cabbage will keep his men safe from scurvy.

She’s loaded with red and blue beads, iron nails, hatchets, small mirrors and children’s play dolls, gifts and talk pieces for natives across the Pacific. She’s loaded with state-of-the-art navigational instruments, a newly engineered azimuth compass to find magnetic north; a vertical compass to measure the angle of dip; brass quadrants; sextants and precious cargo that’s been stored almost as carefully as the 1600 gallons of spirits, two cutting-edge astronomical telescopes supplied by the Royal Society that, on February 16, 1768, petitioned King George III to finance this bold scientific expedition across the vast blue Pacific to study and observe the 1769 transit of Venus from the island of Tahiti as it passes across the sun.

Young Nick hears history in the making. The sound of the animals on board. Pigs and chickens for livestock. A milking goat. The Devon gulls circling in the sky. The sound of cheering well-wishers on the docks.

He hears the whispers and rumours about the dashing and esteemed Mr Joseph Banks. How the captain bit his tongue when this gentlemanly fellow of the Royal Society, this brilliant and bold 25-year-old hunter-hipster-botanist, loaded up Cook’s already crowded vessel with a party of two artists, the gifted specimen sketcher Sydney Parkinson and landscape specialist Alexander Buchan, a secretary, four servants — two of them most likely products of the booming transatlantic slave trade — two hunting dogs, and an endless gangplank parade of boxed natural history reference books, scientific preservation materials, specimen tins and jars, curious underwater telescopes, dragnets for fish studies and reams of paper for reports and drawings.

Word’s spreading across the ship that Banks is the owner of a large inherited fortune, not to mention half of Lincolnshire county, who has spent as much as 10,000 of his own pounds on the once-in-a-lifetime expedition. More rumoured words follow about how, the night before he travelled here to Plymouth to board Endeavour, he was enjoying a night at the opera with an early true love, Miss Harriet Blosset, a wealthy young woman the great botanist calls “the fairest amongst flowers”.

A year from now, Banks will show extraordinary courage traipsing through unknown lands across the Pacific in search of countless unidentified specimens. But some say he showed little courage that night at the opera, failing to confess to Miss Harriet his plans to sail off into the treacherous South Seas in the name of science.

Young Nick hears whispers of Terra Australis Incognita. The unknown southern land. A handful of loudmouth rogues on board say there has to be a great southern continent, a vast super landmass rich with wild new life and certain wealth for all who walk upon it. A geological counterpoise to all that land in the north, say these rogues with pirate smiles, not yet realising volumes of water can weigh more than measures of dirt.

But the grand whispers of new silks and spices spread unbridled. Tales of silver and gold. Their overt mission is to find Venus above Tahiti. Accurate readings of when it passes the sun will help determine the “astronomical unit” — a unit of length roughly the distance from the Earth to the sun — which, in turn, will help 18th-century navigators calculate the observer’s all-important and oft-elusive longitude.

But it’s the ship’s covert mission that has their full hearts skipping beat. The captain’s so-called “secret instructions” from the British Admiralty, penned July 30, 1768. Not quite secret enough to stop the locals from talking about them over pints of warm beer in every ale house in Plymouth.

Whereas there is reason to imagine that a Continent or Land of great extent may be found to the Southward of the Tract lately made by Captn Wallis in His Majesty’s Ship the Dolphin (of which you will herewith receive a Copy) or of the Tract of any former Navigators in Pursuit of the like kind, You are therefore in Pursuance of His Majesty’s Pleasure hereby requir’d and directed to put to Sea with the Bark you Command so soon as the Observation of the Transit of the Planet Venus shall be finished and observe the following Instructions. You are to proceed to the Southward in order to make discovery of the Continent abovementioned until’ you arrive in the Latitude of 40°, unless you sooner fall in with it. But not having discover’d it or any Evident sign of it in that Run you are to proceed in search of it to the Westward between the Latitude beforementioned and the Latitude of 35° until’ you discover it, or fall in with the Eastern side of the Land discover’d by Tasman and now called New Zeland. If you discover the Continent abovementioned either in your Run to the Southward or to the Westward as above directed, You are to employ yourself diligently in exploring as great an Extent of the Coast as you can, carefully observing the true situation thereof both in Latitude and Longitude, the Variation of the Needle; bearings of Head Lands Height direction and Course of the Tides and Currents, Depths and Soundings of the Sea, Shoals, Rocks and also surveying and making Charts, and taking Views of Such Bays, Harbours and Parts of the Coasts as may be useful to Navigation. You are also carefully to observe the Nature of the Soil, and the Products thereof; the Beasts and Fowls that inhabit or frequent it, the Fishes that are to be found in the Rivers or upon the Coast and in what Plenty, and in Case you find any Mines, Minerals, or valuable Stones you are to bring home Specimens of each, as also such Specimens of the Seeds of the Trees, Fruits and Grains as you may be able to collect, and Transmit them to our Secretary that We may cause proper Examination and Experiments to be made of them. You are likewise to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value, inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard; taking Care however not to suffer yourself to be surprized by them, but to be always upon your guard against any Accidents. You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.

Young Nick hears the sound of new acquaintance. The sound of adventure. And the sound of the boy servant’s master, the surgeon William Monkhouse, whose clomping heels he scurries behind dutifully, chancing glances left and right at the men he’ll live upon the sea with for the next three years.

Men like the Scotsman Forby Sutherland, the ship’s poulterer who’ll turn all the wild Pacific game birds shot by Banks into dinner. Sutherland won’t make it home. He’ll succumb to consumption on April 30, 1770; be buried on the banks of Botany Bay, in a land the world will come to call Australia.

Men like Richard Orton, the captain’s clerk, who’ll scribble some of the most important notes in the history of world exploration, a man with a keen mind and a keener embrace of the bottle who’ll have his ears mutilated by a mystery crewman after a long moonlight bender.

Men like Zachary Hicks, Cook’s second-lieutenant, the modest man from London’s East End whose name will forever be tied with the birth of modern Australia. He’s already suffering from the early onset of the consumption to which he, too, will succumb before he can make it home.

Men like Stephen Forwood, the ship’s gunner, who’ll grow popular among these men for his remarkable skill for illegally tapping the rum casks on the quarter deck. Men like Robert Molineux, the ship’s master, from the north bank of the Mersey, who’ll take a liking to the fat and fire-roasted rats of Tahiti. And boys like Isaac Smith, a 16-year-old midshipman, the loyal cousin to Cook’s wife, Elizabeth, who’ll be a man by the time he takes one fateful step on to the complex shores of Australian history.

There are carpenters and cooks. Sailmakers and armourers. Quartermasters and marines. There are men from inland England and coastal Wales and Dublin and Cork, and one from New York. And the fates of all these men rest upon the shoulders of one.

He passes Young Nick on the deck. The boy’s going one way and Lieutenant James Cook is going the other: towards his destiny, towards Terra Australis Incognita, towards immortality.

He towers over the boy, his long nose drawing in that cool English air he won’t smell again for three years.

He’ll spend these years teaching, instructing, disciplining, admonishing and inspiring men on deck, or mapping, researching and recording down in the Great Cabin, sitting down amid Joseph Banks’s cluttered and expanding below-deck natural history museum, or bending over so his head doesn’t bump the cabin ceiling.

For three long years, he’ll squeeze his tall frame into portless and boxy sleeping quarters lit only by whale oil lamp. David Samwell, a naval surgeon and poet who will later join Cook on his mighty Resolution voyage, will describe him as “a modest man, and rather bashful; of an agreeable lively conversation, sensible and intelligent”.

“In temper he was somewhat hasty, but of a disposition the most friendly, benevolent and humane,” Samwell will write. “His person was above six feet high: and, though a good-looking man, he was plain both in dress and appearance. His face was full of expression: his nose extremely well shaped: his eyes, which were small and of a brown cast, were quick and piercing; his eyebrows prominent, which gave his countenance altogether an air of austerity.”

He’s a lieutenant in rank only. The men will call him captain at sea and some would gladly call him commander if they could. Ambitious, curious, restless.

A self-made man. An avid reader. A clean freak. A visionary. A born and hardened seaman who served in the Seven Years War; who proved himself a surveyor of unparalleled precision mapping Newfoundland with its wildly unpredictable and jagged cliff edge coastline.

A brilliant mathematician from boyhood, with a star system knowledge earned the hard way, by staring up at the sky until his neck muscles hurt as a grocery boy in his first job in the fishing village of Staithes, 32km outside the seaport of Whitby; by walking on to any fishing boat in Whitby harbour that would allow him on it; by serving below deck on naval frigates, rising up, within two short years of service, to ship’s master of a British man-of-war.

Husband, father of six, absentee dad. He pays the bills the only way he knows how, by sailing and mapping the world. He keeps his feelings close. He’s a taker of only calculated risks, with a profound knowledge of the 18th-century British male mind and how to manage it.

“He is absolutely a man of his age,” says Michelle Hetherington, senior curator, National Museum of Australia, one of the nation’s most accomplished Cook historians.

“He is an 18th-century man who uses the opportunities that are available to improve his position in life. He’s ambitious, he’s talented and he works really, really hard. He knows the psychology of his men. He’s compassionate. He’s heroic, but I also think he has been heroised to such an extent that we lose important information about him. He was just a man who was doing his job and he brought to it some really useful skills and a huge amount of application.

“He was obviously good at what he did but if we see the voyage as just him, that he and he alone was the great discoverer, then the spotlight that focuses purely on Cook puts everything that’s behind him into darkness. That upsets me. He’s the pointy end of the ship but where’s all that power coming from? Who else was there? What else was going on? And what allowed him to do what he could do?”

The wind breaks northwest and the captain calls for the mainsail to be unfurled. At 2pm, the Plymouth wind fills Endeavour’s billowing sails and she carves her way out to sea, toward Rio de Janeiro, about three months’ sail south.

At a writing desk the size of a 21st-century doll’s house, the captain writes on a sheet of paper that will be bound with hundreds of other sheets into a journal that, come the year 2017, will be housed in the National Library of Australia in a city called Canberra. Its loyal custodians will call it “MS1”. Manuscript One. The foundation document from which all research into the British colonisation of Australia begins. Young Nick will be found in that manuscript, along with the great Joseph Banks and Sutherland and surgeon Monkhouse and Hicks and that quiet, deep-thinking captain.

“At 2pm got under sail and put to sea having on board 94 persons including Officers Seamen Gentlemen and their servants…,” the captain writes. Day after day Cook will document the fates of these 94 persons in his journal. Three of the 94 will drown. Two will freeze to death. One will be discharged. One will desert the ship. Some 40 men on board won’t see the shores of England again.

Maybe it’s the artificial lighting in the box, but something about MS1 makes it radiate. It glows with history. Something about it has you slowing your steps when you near it, has you softening your voice to an awed whisper. “The journey this book has made,” you gush.

“It’s all in there, the whole story,” whispers historian Susannah Helman, exhibitions curator for the NLA. “It’s in his own hand. You can tell what was going through his mind.”

Helman is in the planning phase for a sweeping exhibition the library is hosting in commemoration of next year’s 250th anniversary of the Endeavour’s epic voyage of discovery. MS1 looms large in her plans.

“I’m interested in Cook, the man and the myth,” she says. “He’s such a huge figure. As the anniversary draws around I believe it’s timely for us to re-examine our connection to Cook. He represents so many things to Australians. What does he mean to us today?”

How did that first epic voyage of discovery shape our nation? What does Captain Cook mean to every indigenous Australian in 2017? Where does this breathtakingly brave and towering explorer fit into the story of us?

She leans over the yellowing journal, locked in a clear display box inside the library’s Treasures Gallery, open on an entry for Wednesday, November 15, 1769. “I turn the pages every four months,” she says. “Every page is my favourite. He’s in New Zealand right now.”

By the time he writes on the two fragile 250-year-old pages in front of her, the captain’s long left behind memories of Tierra del Fuego, off South America’s southern tip, with its locals he considers “perhaps as miserable a set of people as are this day upon Earth”. Two of Banks’s servants have died of exposure on doomed specimen collection field trips. Mountainous waves of the South Atlantic have tossed the humble coal carrier around so violently, Banks’s work desk crashed over the cabin floor in a mess of books and science equipment. “A very disagreeable night,” writes Banks, with remarkable understatement.

Starry-eyed romantic Sydney Parkinson has survived so many storms, he’s come to appreciate every second he breathes on this increasingly strange planet.

How amazingly diversified are the works of the Deity within the narrow limits of this globe we inhabit, which, compared with the vast aggregate of systems that compose the universe, appears but a dark speck in the creation! A curiosity, perhaps, equal to Solomon’s, though accompanied with less wisdom than was possessed by the Royal Philosopher, induced some of us to quit our native land, to investigate the heavenly bodies minutely in distant regions, as well as to trace the signatures of the Supreme Power and Intelligence throughout several species of animals, and different genera of plants in the vegetable system, “from the cedar that is in Lebanon, even unto the hyssop that springeth out of the wall”: and the more we investigate, the more we ought to admire the power, wisdom, and goodness, of the Great Superintendant of the universe; which attributes are amply displayed throughout all his works; the smallest object, seen through the microscope, declares its origin to be divine, as well as those larger ones which the unassisted eye is capable of contemplating.

Endeavour’s rounded treacherous Cape Horn and met the mighty Pacific Ocean. Cook has found Tahiti and Banks has found Tahitian women, three of whom enchanted him — for strictly anthropological reasons — with a memorable display of island cloth recorded in his journal:

(T)he foremost of the women, who seemd to be the principal, then stepd upon them and quickly unveiling all her charms gave me a most convenient opportunity of admiring them by turning herself gradualy round: 3 peices more were laid and she repeated her part of the ceremony: the other three were then laid which made a treble covering of the ground between her and me, she then once more displayd her naked beauties and immediately marchd up to me, a man following her and doubling up the cloth as he came forwards which she immediately made me understand was intended as a present for me. I took her by the hand and led her to the tents acompanied by another woman her freind, to both of them I made presents but could not prevail upon them to stay more than an hour. In the evening Oborea and her favourite attendant Otheothea pay us a visit, much to my satisfaction as the latter (my flame) has for some days been reported either ill or dead.

Cook has accomplished his chief task of measuring the transit of Venus across the sun, though not to his satisfaction.

There was a troubling “black drop” effect when Venus left the very edge of the sun where it drew out like a teardrop — as opposed to a perfect circle — making it impossible for Cook and Endeavour’s seasoned official astronomer Charles Green to be certain of the precise time Venus left the sun’s cusp.

“That was a tense moment,” says a colleague standing beside Helman, historian Martin Woods, the NLA’s curator of maps.

“It’s one of those key moments in the journal where you can feel the whole mission is hingeing on one moment, on one page in the journal.

“They have to set up on this rock in the Pacific, set up these complex astronomy instruments and take these measurements and so on, and the weather isn’t in their favour, and you’re always thinking, ‘Well, what’s gonna happen next’? You literally do feel that. It’s such a page turner.”

Woods nods at a mahogany and rosewood fall-front writing desk resting next to Cook’s journal, believed to be the very desk on which Cook wrote journal entries and letters on his Pacific voyages.

“There’s a secret compartment in it where he might have kept his more important documents,” Woods says.

“It might be where he kept the orders for the voyage, for example. The strategically sensitive orders are the ones saying he should try to determine whether there was an east coast to what the Dutch called New Holland.

“After marking the transit of Venus, it was up to him to decide for himself whether he was going to do this other mission. And it’s mission impossible. But, of course, off he went.”

He sails from Tahiti in search of the great southern continent. Helman casts her eyes over Cook’s words about his travails mapping the North and South islands of New Zealand.

“He’s gone out in the pinnace, having encounters with indigenous people,” she says. She points at a hard-to-read scribble. “He’s writing about the weather here,” she says. “There’s always something about the weather.”

Cook writes in a grand 18th-century cursive, “d” letters like samurai swords and “y” letters like dragon tails.

The book is a dizzying brain dump of sea-based history-in-the-making. There are lines crossed out where he’s checked his thoughts, measured his meanings, softened or hardened his opinions. There are random ink runs where you can almost feel Endeavour rocking as it passes Africa or South America and punishing Cape Horn.

He writes dates in a scarlet-coloured ink that has become the basis of an entire research project. Another research project entirely could be devoted to the journal’s paper stock; another to how many members of the Cook family held the journal before it made its way to the 1923 Sotheby’s sale in London where the Australian government bought it for about £5000; another to Cook’s habit of writing sudden or follow-up thoughts between written lines.

He writes about his strategic faults and successes and misfortunes and providences but he rarely writes about his feelings. No aching passages of longing about how much he misses his wife, Elizabeth Cook, who would outlive him by almost half a century, the beloved mother of six children, Nathaniel, Joseph, Elizabeth, George, James and Hugh.

“He really took to heart the mission to record what they saw and who they met,” Helman says. “That’s what he does. And he’s not afraid to be truthful. He reports things as he sees them.

“He was the commander of the ship and that ship was a little mini society. He was responsible for everybody. It must have weighed incredibly heavily upon him. He was ultimately responsible for getting these men home.”

He leads on platforms of discipline and diet.

“He didn’t act like your modern CEO, thank goodness,” says the NMA’s Hetherington. “He had real power. He had the power of life and death over people on that ship. But his role was both of an inspiring fatherly figure as well as commander.

“Any peep of disagreement would be punished with the lash and you could be hanged for mutiny. The men knew to behave well in front of this guy because he has your career in his hands.

“The thing about the navy is it’s one of those services where there’s great opportunity for promotion. You can come in as somebody without huge amounts of money, like Cook, and you will be promoted on your merits.

“And, of course, there’s such a high death rate, there’s always a vacancy coming up.”

“Life expectancy wasn’t high and the risks were great,” says Woods. “In the Dutch East India Company something like a third of their total complement died on the voyages they took from Europe to Australia, so there was a pretty high probability of death, but those were the days. There’s the seamen of the world, and then there’s everybody else who lives safely back at home.

“It’s physical courage. But what amazes me about Cook is that his courage is combined with a care, a concern for all people.

“You can read it into Cook. You hear it in him in the journal. He understands and empathises with the people he meets on that voyage.”

Susannah Helman leaves the library’s Treasures Gallery and takes an elevator to an off-limits storage area in the library’s upper levels. She pulls a set of keys from her pocket.

“These are the special keys,” she says. For unlocking doors to special places. A room with a wide window overlooking Lake Burley Griffin. A large workspace is covered in reams of Mylar and rolled preservation plastic. She slides out a thin and wide metal storage drawer to reveal a wooden walking stick.

“He had to look the part,” Helman says.

It’s the captain’s walking stick. More for show than for support on deck.

She opens a second drawer and pulls out a metal utensil, two pointy and sharp metal prongs fixed to a handle, 18.3cm in length.

“That’s Captain Cook’s fork,” she says.

The Endeavour sails west from New Zealand and Cook’s fork digs into another plate of sauerkraut. The captain’s obsessed with diet. He counsels his men daily on the importance of eating fresh meat and greens.

On his long way down from Brazil he smiled especially fondly on any man who climbed aboard from a stopover with a handkerchief full of foraged greens, though their cracked and weathered lips are more naturally yearning to wrap around a slice of the crackling fat encasing a salted pork, the kind of loose diet delicacy that invites the dreaded scurvy.

Crossing the Tasman Sea, on April 19, 1770, Banks eyes a minor miracle of the ocean. It’s a mighty waterspout as high as a modern city building, a tubular saltwater vortex rising up from the ocean into a fulsome cloud, twisting and spouting for almost 15 minutes. He writes of it in his journal.

It was a column which appeard to be of about the thickness of a mast or a midling tree, and reachd down from a smoak colourd cloud about two thirds of the way to the surface of the sea; under it the sea appeard to be much troubled for a considerable space and from the whole of that space arose a dark colourd thick mist which reachd to the bottom of the pipe.

When it was at its greatest distance from the water the pipe itself was perfectly transparent and much resembled a tube of glass or a Column of water, if such a thing could be supposd to be suspended in the air; it very frequently contracted and dilated, lenghned and shortned itself and that by very quick motions; it very seldom remaind in a perpendicular direction but Generaly inclind either one way or the other in a curve as a light body acted upon by wind is observd to do. During the whole time that it lasted smaler ones seemd to attempt to form in its neighbourhood; at last one did about as thick as a rope close by it and became longer than the old one which at that time was in its shortest state; upon this they Joind together in an instant and gradualy contracting into the Cloud disapeard.

It’s a wondrous welcome, of a kind. Far beyond that waterspout rests another natural miracle of dirt and rock, a place some 24 million people will come to call the greatest place on earth.

It’s second lieutenant Zachary Hicks who spots it first, leaning out from the masthead. Land. Some 7,686,850sq km of it.

“The face of the Country green and woody but the seashore is all a white sand,” writes Cook.

On deck, young Nicholas Young leans hard against Endeavour’s side, hope in his heart, heart in his throat, squinting his eyes to catch his first glimpse of Australia.

Return to the Cook Endeavour series page here